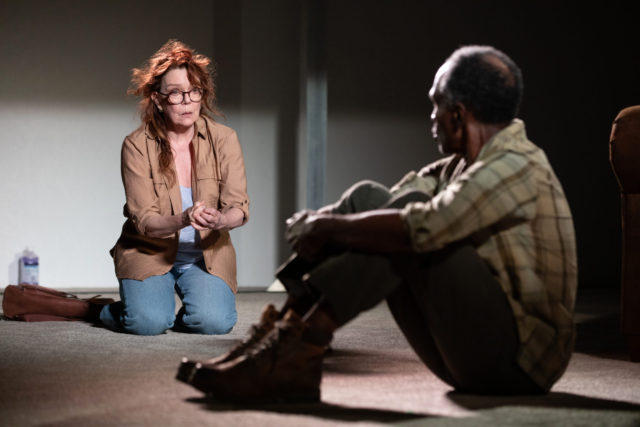

Ani (Deirdre Lovejoy) and Jen (Donnetta Lavinia Grays) go about their jobs in different ways in Sarah Mantell’s latest play (photo by Valerie Terranova)

IN THE AMAZON WAREHOUSE PARKING LOT

Playwrights Horizons, Mainstage Theater

416 West 42nd St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Through November 17, $62.50 – $102.50

www.playwrightshorizons.org

The unofficial motto of the US Postal Service is “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds.” The quote was taken from The Persian Wars by Herodotus, who is alternately known as the Father of History and the Father of Lies.

In Sarah Mantell’s Susan Smith Blackburn Prize–winning In the Amazon Warehouse Parking Lot, in the aftermath of an unnamed apocalyptic event, there is no more post office, no stores, only a society hanging on by a thread. All that is left are scattered people and — Amazon. Thanks, Jeff Bezos.

The play begins in an Amazon warehouse, where Jen (Donnetta Lavinia Grays) is taking packages off a conveyor belt. She is surprised when a new employee, Ani (Deirdre Lovejoy), shows up to work replacing Chris, the outbound supervisor. We never learn what happened to Chris; in this America, set only one generation in the future, people disappear without explanation.

As Jen places the boxes in vertical metal carts, she calls out the names on their address labels: “Flagstaff, Arizona.” “Carvers, Nevada. Oh that’s good. Wasn’t sure I’d see Nevada again.” “Rutland, New Hampshire.” “Greensboro, that’s a good one too. Haven’t gotten much North Carolina in a while.”

When Ani does not call out the names of the cities where her packages are going, Jen gets upset. “If you don’t read the labels, how will you know what’s going on out there?” she asks. Ani ignores her.

Jen also works shifts with El (Sandra Caldwell), who does call out the addresses. They see a package that seems to be addressed to Ash’s (Tulis McCall) cousin, in Ohio, and they memorize the exact location because writing it down is forbidden; they are subject to random searches by security guards. It slowly becomes evident why the addresses and the existence of other states, cities, and towns are so important.

When they’re not on the line, the crew of seven — Jen, Ani, El, Ash, Horowitz (Barsha), Sara (Ianne Fields Stewart), and Maribel (Pooya Mohseni), all queer women, nonbinary, or trans — gather outside by a highway next to a stunning mountainous landscape. They talk about work, share food, play a game called Werewolf, wonder what their coworkers might have done for a living in the before times, and recall moments from their past, like something as simple as eating an apple; in addition, most of the characters get their own personal monologue.

Jen sums it all up when she says, “Listen. It’s not like I don’t hate it. All the places, the names. All the calculating. On the days I don’t think I can take it anymore, I think about my friends who are searching for people, right? And if those names come by, I try to picture I’m like a waterslide, like it comes through me and I don’t have to hold it. It’ll just get where it’s going ’cuz I’m here?”

A group of queer Amazon workers try to plot their future in Sarah Mantell’s In the Amazon Warehouse Parking Lot (photo by Valerie Terranova)

Presented in association with Breaking the Binary Theatre, In the Amazon Warehouse Parking Lot paints a bleak portrait of the near-future, run by a corporate monolith where people are merely names on boxes, not individuals with real purpose. There is no communication, no connections; packages revolve on an overhead conveyor belt and are ultimately shipped off to destinations that might barely exist. It’s a world where no one can travel, except from Amazon job to Amazon job; the trucks will roar down that highway by the warehouse, but not the crew, who wonder where their friends and relatives are, whether they are alive or dead. The only thing that matters is that the packages get delivered, but it is never implied what might be in them. What other companies are even out there, still doing business?

Emmie Finckel’s scenic design switches between the packing room and the outside, a melding of utopia and dystopia; neither place offers the staff any sense of freedom. Cha See’s lighting and Sinan Refik Zafar’s sound create an enveloping sense of potential doom that could come at any moment. Mel Ng’s costumes feature the familiar Amazon orange vests, under which the employees wear regular clothing, sometimes with an edge, as with Ash’s T-shirt that depicts gay rights activist Marsha P. Johnson. (In the script, Mantell notes, “All of the characters are queer. . . . Jen is androgynous / butch / masc. I think El probably is too. Sara is transfeminine and high femme. At least half the cast should be gender nonconforming. The majority of the cast should be BIPOC — and Jen and Sara must be. Sara is ‘the baby,’ but the others are written to be over fifty. My hope is that these roles become something my generation of actors can age towards, and that by the time they get here, the pool will look very different than it does now.”)

Mantell’s (The Good Guys, Tiny) dialogue is sharp and incisive, and Battat (Problems Between Sisters, Layalina) directs with an astute sure-handedness. The ensemble is outstanding, led by Lavinia Grays (Men on Boats, In the Next Room or The Vibrator Play), who is like a stand-in for the audience, wanting to find out more, even if it involves taking risks. If this kind of apocalypse is ever going to happen, this is the group you want to be with. Then again, at that point, it might be too late. Fiddling with her Amazon device, El says, “Sometimes I think if I drop it just right it’ll short circuit and reconnect itself to the world beyond the corporation,” to which Maribel responds, “What world?”

As Herodotus also wrote, “One should always look to the end of everything, how it will finally come out.”

Just like Amazon, in the end, Mantell’s gripping play delivers.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]