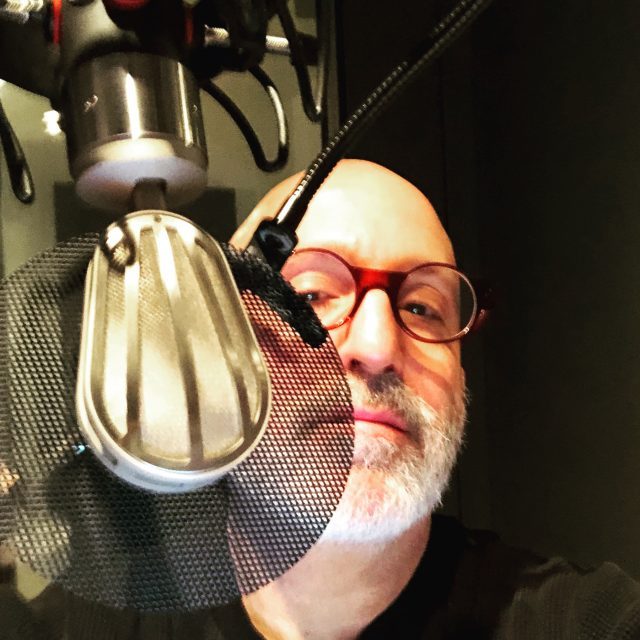

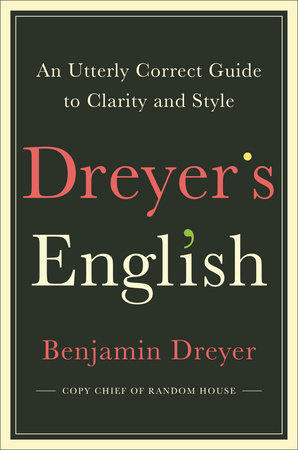

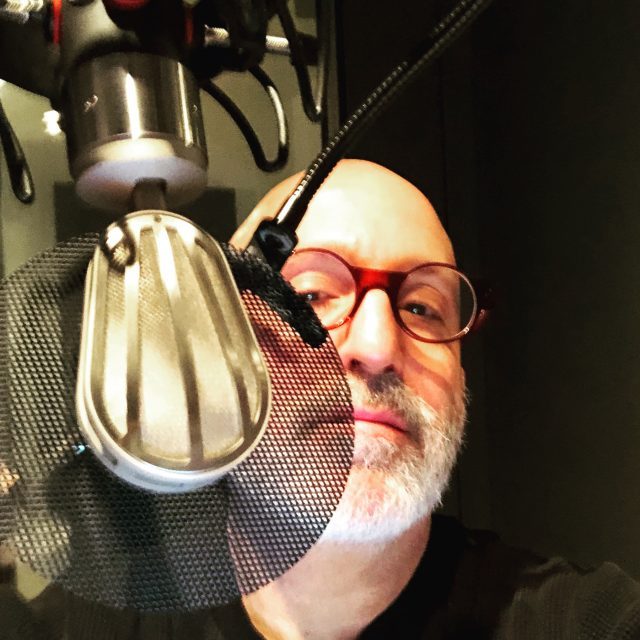

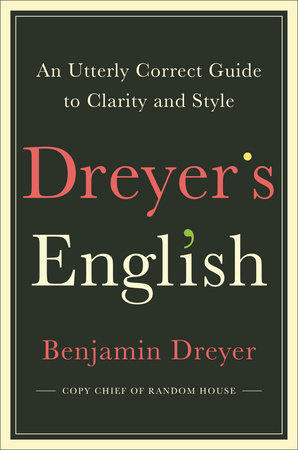

Ben Dreyer records the audio version of his debut book, Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style

Barnes & Noble

150 East 86th St. at Lexington Ave.

Thursday, January 31, free, 7:00

212-369-2180

stores.barnesandnoble.com

www.penguinrandomhouse.com

When Random House vice president, copy chief and executive managing editor Benjamin Dreyer agreed to do a twi-ny talk in conjunction with the publication of his phenomenal new book, Dreyer’s English: An Utterly Correct Guide to Clarity and Style (Random House, January 29, 2019, $25) I knew the interview had to be done via e-mail and not over the phone or in person, since Dreyer makes his living with the written word. (Yes, there is at least one error in the previous sentence; please see the paragraph below in bold to find out why.) Just like Ben, Dreyer’s English is a thoroughly engrossing read, both funny and expertly knowledgable. In the book, he covers such general matters of style as grammar, spelling, and punctuation along with more specific looks at what he calls “peeves and crotchets,” “confusables,” and “trimmables.” He lends insight to plural possessives, the serial comma, initialisms, parentheses, common mispellings, capitalization, and the “hoi polloi,” exploring certain items farther, more in depth, begging the question, “Do I need more than just autocorrect and spellcheck to write well”?

In the main text and detailed footnotes, Dreyer references such literary giants as Dickens, Fitzgerald, Hans Christian Anderson, J.R.R. Tolkien, George Bernard Shaw, and James Joyce; an avid theatregoer and old movie fan, the book also includes examples involving Katharine Hepburn, Liza Minnelli, Noel Coward, Joan Crawford, Abbot and Costello, Zoe Caldwell, Lon Chaney Jr., and Ingrid Bergman, among many others. The fact that Dreyer reserves his most deepest admiration for Shirley Jackson, the 20th century author of such novels as the Haunting of Hill House and such short stories as “The Lottery” is not surprising. Dreyer actually got a chance to copy edit previously-unpublished pieces by Jackson; in one of the best footnotes in his book, he admits to typing out the complete Jackson short story, “The Renegade” — “to see whether doing so might make me better appreciate how beautifully constructed the story was. It did.” I’m considering typing out some of Dreyer’s paragraphs to remind me of some of the style elements he espouses so entertainingly in the book, especially “lie/lay/laid/lain.”

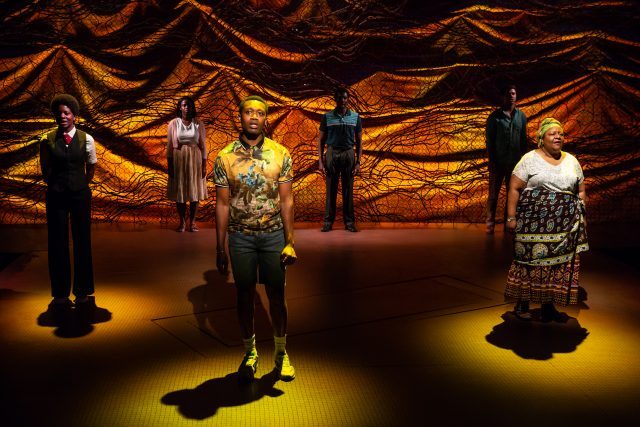

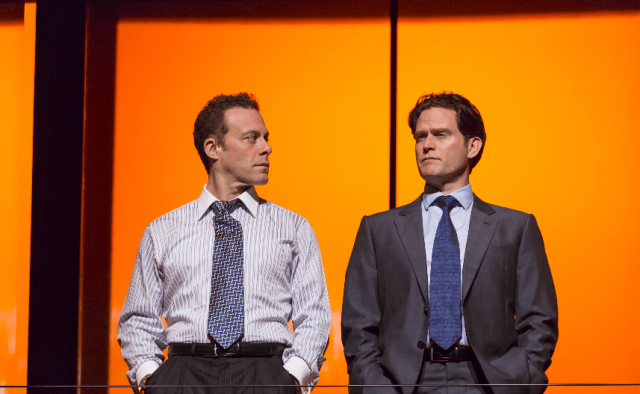

A legend in the industry, I’ve known Dreyer since 1995, when I was a managing editor at Random House imprint Ballantine Books. He really sums up the primary responsibilities of a copy editor at the very start of Dreyer’s English (which has received praise from such literary stalwarts as Elizabeth Stout, George Saunders, Jon Meacham, Amy Bloom, and Ayelet Waldman and Michael Chabon): “I am a copy editor. After a piece of writing has been, likely, through numerous drafts, developed and revised by the writer and by the person I tend to call the editor editor and deemed essentially finished and complete, my job is to lay my hands on that piece of writing and make it . . . better.” He also recorded the audiobook, joined by his good friend and two-time Tony nominee Alison Fraser. (You can listen to a clip here.)

Dreyer will be at the Barnes & Noble at Eighty-Sixth & Lexington on January 31 at 7:00, signing copies of the book and speaking with award-winning Random House author Peter (Ghost Story) Straub. Its a great opportunity to join the Dreyer cult we’ve all been apart of for decades. He’ll also be taking copyediting questions on Twitter on February 1 from 12:30-1:30.

SIGNED BOOK GIVEAWAY: In the paragraphs above are at least a dozen grammatical errors that Dreyer deals directly with in his book; whoever correctly identifies the most will win a signed copy for free. Just send your name, daytime phone number, and list of mistakes to contest@twi-ny.com by Friday, February 1, at 3:00 pm to be eligible. All entrants must be twenty-one years of age or older; in case of a tie, one winner will be selected at random.

twi-ny: How long has this book been percolating inside you? Was there a final impetus that helped you go ahead with it?

benjamin dreyer: Back in the 1980s I’d written a bit of short fiction and was a regular contributor to Chicago’s then premier gay newspaper, Windy City Times, writing mostly on film and theater. Those writing aspirations fell by the wayside — I developed awful writer’s block, particularly insofar as writing fiction was concerned — and as I fell into freelance proofreading and then copyediting, I, happily, felt deeply satisfied that I was making a contribution to writing, even if I wasn’t writing myself, and I let the writing thing go. (As a friend said, “It’s too painful to be in a constantly anxious state of Not Writing. Better to let it go than to make yourself miserable on a daily basis.”) After I joined Random House as a production editor in 1993 and eventually became copy chief and managing editor, I pretty much stopped copyediting — there are only so many hours in the day, after all, and I have a lot of job. But: About six years ago I found myself invited to copyedit a novel — Elizabeth Strout’s excellent, to say the least, The Burgess Boys — and simply setting green pencil to paper again filled me with real joy; I’d forgotten how much I like to copyedit. And that sense of joy somehow rekindled my desire to write. I guess I was having a moment. So one afternoon I rather barged into the office of Random House publisher Susan Kamil and began to, well, burble at her about my desire to write a book about copyediting. She interrupted my burbling, suggested that if I wanted to write and particularly publish a book I might do well to have an agent, and — to make a longish story shortish — a few months later there I was, under contract to write the book that’s just now going on sale.

twi-ny: You have spent your entire career working on other people’s books, but now you’re the one whose words are being line edited, copyedited, proofread, and designed. What was that experience like? Did you enjoy being copyedited, or was it painful?

bd: That thing about “I hate writing, I love having written”? Well, if I didn’t quite hate writing, except when I did, I loved being edited. I’ve had the support of three great editors at Random House, plus my agent’s keen oversight, and they were all wonderful at encouraging me and challenging me — with of course a healthy dose of “Could you just finish it, please?” The funny thing is, it took me an awfully long time to find my voice, but once I found it, once I really let my writer freak flag fly, they were all “Yes, yes, yes, go, go, go.” Of course they asked me to expand on things they thought I wasn’t addressing fully enough, and occasionally I was asked to dial it down a bit. (If you’ve read the book, your response to that might be “And apparently you didn’t.” But truly, I did.) As to the copyediting, well, that was just amazing. I did request a particular freelance copy editor I used to hire constantly back in my production editorial days — I conceal her name here only to discourage people poaching her from RH, but she’s honored in the back of the book if you care to look in the acknowledgments — and she was superb, as I knew she would be. She called me out on any number of my bad habits, including a tendency to insert massive amounts of digression into the middle of a sentence, laughed at my jokes (in the margins, that is), and periodically would offer helpful/necessary rephrasings of text in such a precise imitation of my voice that I’d just pick up her suggestions and stuff them into the manuscript. In short, she did everything for me that I have always tried, as a copy editor, to do for the writers I was copyediting. I felt honored and protected and looked after and properly prodded, and she certainly substantively improved the book. (To answer a question you didn’t ask: A copy editor cannot turn a bad book into a good one, but a copy editor can certainly take a competent or better manuscript and make that thing shine. I think she polished me quite nicely.)

I’d also like to add that the book’s text designer — a colleague of mine for as long as I’ve been at Random House — absolutely, I think, nailed it. Writers often have lots of quibbles over and requests about their text design, but the first time I saw the proposed text design I almost cried, it was simply everything I had envisioned it might be. As a physical object, I think that the book is freaking gorgeous.

twi-ny: Your longtime colleague, Dennis Ambrose, who works for you, served as the production editor on your book. Did that make the process easier or more difficult, being so close to it, as opposed to it being handled by a different publishing company?

bd: Once we established departmentally that a lot of things I do for all our books as managing editor and copy chief I obviously couldn’t do for my own book, it was mighty smooth sailing. Dennis is an absolute pro and managed it all beautifully, and between the two of us we kept me in my lane. Of course it was easy to relax and know I was being taken proper care of because I’ve worked with Dennis for decades watching him take care of the likes of Edmund Morris and Jon Meacham, among others. He knows what he’s doing. And though indeed it’s a bit peculiar to be published by your own house, I wouldn’t have had it any other way. I’ve gotten a lot of love, from all departments, and I’m deeply grateful for it.

twi-ny: Was there a specific item that you really wanted in the book but either your editor editor, the production editor, or the copy editor convinced you otherwise?

bd: Everything’s basically as I set out to write it, and I never felt strong-armed to cut anything (or to add anything, for that matter). Maybe my agent and editors encouraged me to trim some of the book’s voluminous lists, and they were usually right, though every now and then my response to “Can we cut this?” was “Nah,” and there was no brawling about it. Though in typeset pages I did cut some things that even I was bored reading, and I’m glad I did.

twi-ny: In the book, you point out numerous cases in which you don’t follow such publishing bibles as the Chicago Manual of Style, Merriam-Webster 11, and Words into Type. You also noted in a 2012 Random House video that your department does not have a house style. As the copy chief, do you have one favorite choice that goes against generally accepted book publishing style?

bd: We really truly really truly don’t have a house style — except for the silent, don’t-query-it-just-do-it mandating of what some people call the Oxford comma, some people call the serial comma, and I call the series comma. And that doesn’t come from me; that was in place when I arrived at Random House. And that’s scarcely unusual: Almost everyone in book publishing favors that comma, even as many/most journalist types detest it. Maybe once a year, if that, an author objects post-copyediting to the comma, and you just grit your teeth and defer. But otherwise — and again, this is good copyediting practice as it was taught to me — every book gets the copyedit it specifically and uniquely needs, in support of what the author is attempting to do, not in support of what the copy editor or the house thinks is Good Writing. The thing I’m pleased to say about Random House books is that you can never tell by the copyediting that they’re Random House books — except that they’re well copyedited. To perhaps slightly misuse cardplaying terminology: We don’t have any house tells.

twi-ny: The book teaches the reader about grammar, punctuation, spelling, and style, and you often boldly, and with humor, defend your preferences. However, in the acknowledgments, you thank the copy editor for “calling out my worst habits.” Can you share one or two of them here?

bd: Aside from the aforementioned habit of overstuffing the middles of sentences so that on occasion by the time you get to the end of a sentence you can’t recall the beginning, I also violently overuse parentheses. And OK, their overuse reflects the way my brain works — constant digressions and by-the-ways — but after a while, enough is enough. All my editors encouraged me to take things out of parentheses; similarly, there’s a lot of stuff I’d initially relegated to the book’s ocean of footnotes that got moved up into the main text.

twi-ny: In the late 1990s, Random House had an in-house chat room called the Water Cooler on the company intranet, and, in retrospect, it was like an early iteration of social media, complete with controversies over language and political correctness. Since the forum was in a publishing house, the posts tended to be fairly well written, but in today’s world, grammar, punctuation, and style have taken quite a hit on social media. You are an avid user of Facebook and especially Twitter; what are your thoughts on social media’s impact on written language?

bd: Facebook is . . . well, it is what it is, to use a phrase that as a copy editor I’d throttle a writer for using. But I find the language of Twitter — and truly, it speaks its own language — endlessly amusing, and when I’m there I like to speak it. Questions without question marks (or, often, any terminal punctuation at all) make me chuckle, ditto all-cap shouting to express manic enthusiasm or mock alarm. To be quite honest — or, if you prefer, TBQH — as I worked on the book, and for a long time I couldn’t quite figure out what my writerly voice was supposed to sound like, I eventually realized that the voice I was cultivating on Twitter in my self-appointed role as Your Pal the Copy Chief was precisely the voice I wanted to bring to the page: succinct (ish), joshing in the service of making valid points, and mocking my own sense of seriousness, all in an attempt to, simply, try to get people to listen to what I was trying to say, and perhaps to appreciate it and learn something from it without their feeling they were being nagged or hectored.

Ben Dreyer and his husband, Robert, pose with their pooch, Sallie

twi-ny: With that in mind, you also aren’t shy about including your thoughts about our current spelling-challenged, Twitter-happy president in many examples in the book. Are you afraid that such references will date the book or anger readers who lean more to the right than you do?

bd: I think that there are so many things to despise about the current administration — everything, now that I think of it — and its degradation of the English language is, I suppose, scarcely the worst of it, but of course the English language is what I do for a living, and I take personally his (you know, that person whose name I’d just as soon not type) subliteracy and, worse, the endless lying and base distortion of the very meanings of words to suit his poisonous agenda. He has dishonored everything I hold dear as an American and as a human being, and I see no reason to dissemble to avoid angering his cult. Perhaps if we all live long enough and I’m given the opportunity a few years down the pike to revise the book for a second edition I’ll change things up a bit, but for the moment, here in the winter of 2019, I’m quite happy with what the book says, and about whom.

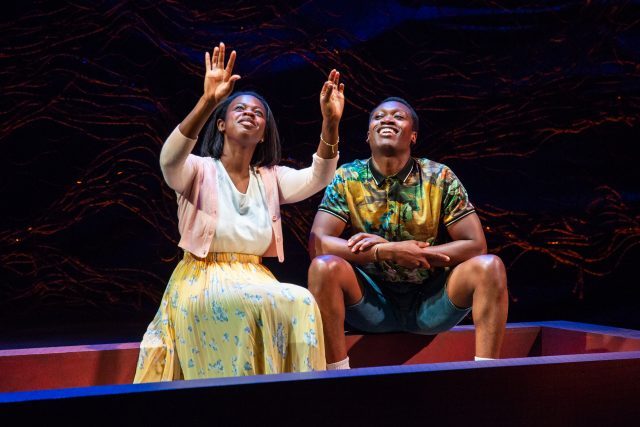

twi-ny: You’re a theater aficionado, and the book is filled with theatrical references, particularly regarding musicals. What have you seen lately that you’ve loved or hated?

bd: I saw Kenneth Lonergan’s The Waverly Gallery a few months ago and was riveted. For one thing, it’s a first-rate script, as one expects from Lonergan, and as a person of a certain age whose parents are of a certain age plus a few decades, I found it harrowing, and I like theater that’s harrowing. For another thing, Elaine May gave a titanically good performance. She’s so good at portraying a woman who’s losing her mental moorings that in the opening scene I found myself anxious for her as an actress; soon enough, to be sure, you realize that she’s doing what she’s supposed to be doing: She’s acting. (I was told afterward by people who were highly familiar with the play that she’s line-perfect down to the very commas.) Looking forward, I’m pleased that Lincoln Center Theater is about to mount a new John Guare play. I think that his Six Degrees of Separation is one of the greatest plays of my lifetime, and I’m always keen to see what he has on his mind.

twi-ny: The other night I saw a show called Say Something Bunny!, the title of which desperately needed a comma, especially since the script, which was given out to everyone as part of the show, has a comma when those words appear in dialogue. What theatrical grammatical error makes you the most crotchety?

bd: Everyone likes to make fun of Alan Jay Lerner’s inability to distinguish between “hanged” and “hung” in My Fair Lady, so let’s not do that one again. OK, the other day I was listening to the original cast recording of Hairspray — and of course we all know never to refer to theatrical cast recordings as soundtracks, right? — and as happens every time I listen to “Mama, I’m a Big Girl Now” (did I just google it to make sure that it’s not “Momma”? yes I certainly did), when Tracy sings that she “could barely walk and talk so much as dance and sing,” I mutter “No, not ‘so much as’; it’s ‘let alone.’” I mutter a lot. As my husband says — lovingly, I’m reasonably certain — “It must hurt sometimes to live in your brain.” Well, yeah.

twi-ny: At your book launch on January 31, you will be in conversation with one of Random House’s most successful authors, Peter Straub. How did that come about? What are your thoughts on his writing?

bd: When Ghost Story was published in 1979, I remember reading the review in the New York Times Book Review and literally — and by literally, I mean literally — running to my local bookstore to get a copy. And I think that it’s one of the great horror novels of our time. Cut to the mid-1990s, and I’m Peter’s production editor at Random House, first on The Hellfire Club, then on four subsequent books, including Black House, his second collaboration, after The Talisman, with Stephen King. And he’s simply the loveliest man, and a delight to work with and for, and very sharp and funny, so when I was asked with whom I’d like to be In Conversation, he immediately leapt to my mind. And he graciously agreed to support me for the evening. I’m looking forward to it hugely; I haven’t seen Peter in a few years, so it’ll be lovely. And I’m rereading Ghost Story right now, and good Lord I’d forgotten how scary it is.