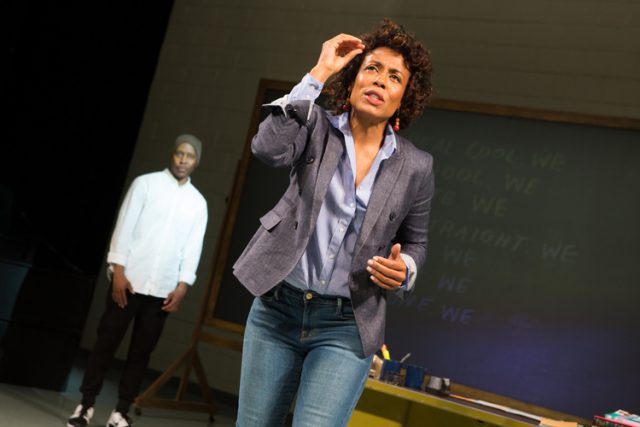

Joe (Edmund Donovan) takes issue with his mother (Judith Ivey) in Samuel D. Hunter’s Greater Clements (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Lincoln Center Theater at the Mitzi E. Newhouse

150 West 65th St. between Broadway & Amsterdam Ave.

Through January 19, $92

212-362-7600

www.lct.org

Samuel D. Hunter takes a sharp snapshot of a downtrodden America in the poignant drama Greater Clements, which ends its run at Lincoln Center’s Mitzi E. Newhouse Theater on Sunday. The play is set in Hunter’s home state of Idaho, the site of many of his works (A Bright New Boise, Lewiston/Clarkston). It’s 2017, and Greater Clements is at the end of the line; the Dodson Mine suffered a horrific tragedy in 1972 and shut down in 2005, and now there’s a referendum to abolish the town as a civic entity, at least in part as a reaction to the flood of wealthy Californians moving in. Maggie (Judith Ivey), who owns the local mine museum, is closing up shop; she has just brought her mentally ill twenty-seven-year-old son, Joe (Edmund Donovan), back from a stint in Anchorage, where he went to get away from some trouble he caused but did not necessarily fully understand. Maggie is visited by her high school flame, the gentle and stoic Japanese-American Billy (Ken Narasaki), and his adventurous fourteen-year-old granddaughter, Kel (Haley Sakamoto); Maggie, who is divorced, and Billy, who is widowed, flirt around with the idea of perhaps getting back together. Meanwhile, Maggie’s friend and employee, Livvy (Nina Hellman), is leading the charge for the town to remain incorporated, and Wayne (Andrew Garman), the police chief, is keeping a close watch on Joe, who appears to have potentially dangerous tendencies.

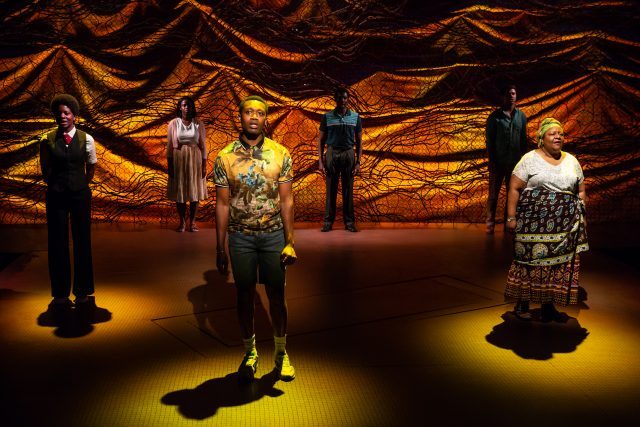

Kel (Haley Sakamoto) tries to befriend Joe (Edmund Donovan) in Greater Clements (photo by T. Charles Erickson)

Shrewdly and discerningly directed by Hunter’s longtime collaborator, Davis McCallum (Stupid Fucking Bird, London Wall), the nearly three-hour Greater Clements explores a wide range of issues, from Japanese internment camps and cancer to mental illness and gentrification, from corporate insensitivity and greed to fear and, perhaps most pointedly, loneliness. Dane Laffrey’s potent, active set, which includes a small part of the audience seated in a corner section virtually amid the action, features a second level that descends from above; unfortunately, the construction requires numerous poles that will occasionally block some of your view as the setting changes from the mine and the museum to a bedroom and living room. Yi Zhao’s lighting is supremely effective in the scenes that take place in the mine itself, putting us inside the dark underbelly of America. Tony and Obie winner Ivey (Steaming, Hurlyburly) is exquisite as Maggie, bringing an intimate, realistic warmth to a stalwart woman who deserves better out of life, but Donovan (Lewiston/Clarkston; Xander Xyst, Dragon: 1) steals the show with his powerful, in-your-face portrayal of a man all-too-aware of his situation but not necessarily capable of controlling it.