Four high school students select a female target for their fantasies in SING A SONG OF SEX

A TREATISE ON JAPANESE BAWDY SONGS (SING A SONG OF SEX) (NIHON SHUNKAKO) (日本春歌考) (Nagisa Oshima, 1967)

Japan Society

333 East 47th St. at First Ave.

Tuesday, April 19, 7:00

Festival runs through April 23

212-715-1258

www.japansociety.org

Japan Society’s 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film” continues April 19 with a complex, hard-to-define work that is not in any way a traditional musical. But then again, it’s by Nagisa Oshima, who didn’t care much for conventions. In 1967, Oshima, who had previously made such controversial films as Pleasures of the Flesh and Violence at Noon, cowrote (with Takeshi Tamura, Mamoru Sasaki, and Toshio Tajima, although much of the film is improvised) and directed Sing a Song of Sex, the original Japanese title of which translates as A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs. The film opens with red liquid dripping on a red background, as if the Japanese flag is being stained with old and new blood. Hikaru Hayashi’s soundtrack chimes in, combining 1960s mystery and sex comedy themes. On a high school campus, many students are protesting the Vietnam War, but four virgin boys, Nakamura (pop singer Ichiro Araki), Ueda (Kôji Iwabuchi), Hiroi (Kazumi Kushida), and Maruyama (Hiroshi Satô), instead are immersed in sexual fantasies involving raping a politically active student they know only as number 469 (Kazuko Tajima). They go out drinking one night in Tokyo with their professor, Otake (Ichizô Itami), as well as three female students, Kaneda (Hideko Yoshida), Ikeda (Hiroko Masuda), and Satomi (Nobuko Miyamoto), who worship the teacher. Professor Otake gets drunk and sings a low-class shanty that demeans women, a Japanese flag behind him. Later he declares, “Bawdy songs, raunchy songs, erotic songs, songs about sex — these are the suppressed voices of the people. An oppressed people’s labor, their lives . . . and their loves. Once people became conscious of these things, they naturally turned to song to express themselves. That’s why bawdy songs represent the history of the people.” He says that he feels sorry for the youth of Japan, who don’t even know they’re being oppressed. Then another drunk man in the bar explains, “So a doomed people sing the songs of a doomed nation? What’s it matter? Japan’s full of doomed people.” That night Professor Otake dies in his hotel room, leaving the three young women to mourn for him and the four young men to continue his bawdy adventures. Meanwhile, Otake’s lover, Takako Tanigawa (Akiko Koyama), becomes involved in the controversy surrounding his death.

Japan Society’s 2016 Globus Film Series “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film” continues April 19 with a complex, hard-to-define work that is not in any way a traditional musical. But then again, it’s by Nagisa Oshima, who didn’t care much for conventions. In 1967, Oshima, who had previously made such controversial films as Pleasures of the Flesh and Violence at Noon, cowrote (with Takeshi Tamura, Mamoru Sasaki, and Toshio Tajima, although much of the film is improvised) and directed Sing a Song of Sex, the original Japanese title of which translates as A Treatise on Japanese Bawdy Songs. The film opens with red liquid dripping on a red background, as if the Japanese flag is being stained with old and new blood. Hikaru Hayashi’s soundtrack chimes in, combining 1960s mystery and sex comedy themes. On a high school campus, many students are protesting the Vietnam War, but four virgin boys, Nakamura (pop singer Ichiro Araki), Ueda (Kôji Iwabuchi), Hiroi (Kazumi Kushida), and Maruyama (Hiroshi Satô), instead are immersed in sexual fantasies involving raping a politically active student they know only as number 469 (Kazuko Tajima). They go out drinking one night in Tokyo with their professor, Otake (Ichizô Itami), as well as three female students, Kaneda (Hideko Yoshida), Ikeda (Hiroko Masuda), and Satomi (Nobuko Miyamoto), who worship the teacher. Professor Otake gets drunk and sings a low-class shanty that demeans women, a Japanese flag behind him. Later he declares, “Bawdy songs, raunchy songs, erotic songs, songs about sex — these are the suppressed voices of the people. An oppressed people’s labor, their lives . . . and their loves. Once people became conscious of these things, they naturally turned to song to express themselves. That’s why bawdy songs represent the history of the people.” He says that he feels sorry for the youth of Japan, who don’t even know they’re being oppressed. Then another drunk man in the bar explains, “So a doomed people sing the songs of a doomed nation? What’s it matter? Japan’s full of doomed people.” That night Professor Otake dies in his hotel room, leaving the three young women to mourn for him and the four young men to continue his bawdy adventures. Meanwhile, Otake’s lover, Takako Tanigawa (Akiko Koyama), becomes involved in the controversy surrounding his death.

Politics, history, war, sex and death converge in Nagisa Oshima treatise

As with so many Oshima films, Sing a Song of Sex walks a dangerously fine line between sociopolitical commentary and lurid, misogynistic exploitation. The film pits many battles, between men and women, the Japanese flag and the American flag (and ads for Coca-Cola), rich and poor, Japanese and Korean (part of the film takes place on the reinstatement of National Foundation Day, a holiday celebrating the history of Japan that had been banned since the end of WWII), educated and uneducated, bawdy Japanese songs about sex and U.S. protest songs (“We Shall Overcome,” “This Land Is Your Land”), and fantasy versus reality, as it becomes more and more difficult to tell what is really happening and what is just the boys’ teenage imaginings. And the ending is likely to enrage you, but you won’t be able to turn away. Although it uses music to tell its story, it’s hard to consider it a musical; in fact, it’s difficult to classify it at all, other than that it’s another strangely bizarre yet beguiling work from an iconoclastic auteur who always challenges the audience. Sing a Song of Sex is screening at Japan Society on April 19 at 7:00; “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film” concludes April 23 with two contemporary delights, Takashi Miike’s The Happiness of the Katakuris and Tetsuya Nakashima’s Memories of Matsuko.

In the 1930s, on the cusp of WWII, Japan was in the process of creating its own cinematic musical genre. One of the all-time classics is the wonderful Singing Lovebirds, a period romantic rectangle set in the days of the samurai. Oharu (Haruyo Ichikawa) is in love with handsome ronin Reisaburō (Chiezō Kataoka), but he is also being pursued by the wealthy and vain Otomi (Tomiko Hattori) and the merchant’s daughter, Fujio (Fujiko Fukamizu), who has been promised to him. Meanwhile, Lord Minezawa (jazz singer Dick Mine) has set his sights on Oharu and plans to get to her through her father, Kyōsai Shimura (Takashi Shimura), a former samurai who now paints umbrellas and spends all of his minuscule earnings collecting antiques. “It’s love at first sight for me with this beautiful young woman,” Lord Minezawa sings about Oharu before telling his underlings, “Someone, go buy her for me.” But Oharu’s love is not for sale. Directed by Masahiro Makino, the son of Japanese film pioneer Shōzō Makino, Singing Lovebirds is utterly charming from start to finish, primarily because it knows exactly what it is and doesn’t try to be anything else, throwing in a few sly self-references for good measure.

In the 1930s, on the cusp of WWII, Japan was in the process of creating its own cinematic musical genre. One of the all-time classics is the wonderful Singing Lovebirds, a period romantic rectangle set in the days of the samurai. Oharu (Haruyo Ichikawa) is in love with handsome ronin Reisaburō (Chiezō Kataoka), but he is also being pursued by the wealthy and vain Otomi (Tomiko Hattori) and the merchant’s daughter, Fujio (Fujiko Fukamizu), who has been promised to him. Meanwhile, Lord Minezawa (jazz singer Dick Mine) has set his sights on Oharu and plans to get to her through her father, Kyōsai Shimura (Takashi Shimura), a former samurai who now paints umbrellas and spends all of his minuscule earnings collecting antiques. “It’s love at first sight for me with this beautiful young woman,” Lord Minezawa sings about Oharu before telling his underlings, “Someone, go buy her for me.” But Oharu’s love is not for sale. Directed by Masahiro Makino, the son of Japanese film pioneer Shōzō Makino, Singing Lovebirds is utterly charming from start to finish, primarily because it knows exactly what it is and doesn’t try to be anything else, throwing in a few sly self-references for good measure.

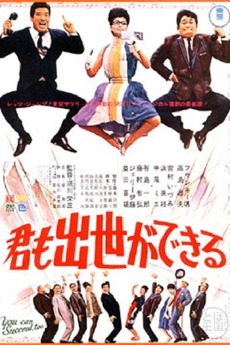

Japan Society’s 2016 Globus Film Series, “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film,” opens April 8 with Eizo Sugawa’s riotous, robust 1964 delight, You Can Succeed, Too. With the Tokyo Summer Olympics approaching, Towa Tourism is locked in a heated battle with Kyokuto Tourism for big travel clients. While Yamakawa (Frankie Sakai) has developed a can’t-miss plan to succeed at Towa — either marry the president’s daughter, become a union leader, or find the president’s weakness and exploit it — his friend Nakai (Tadao Takashima) does not enjoy the urban rat race and would rather settle down in the countryside. When the president, Nobuo Kataoka (Yoshitomi Masuda), returns from a trip to the United States with his daughter, Yoko (Izumi Yukimura), he puts her in charge of the foreign office as she extolls the virtues of efficient American business practices over the old-fashioned Japanese ways. Yamakawa sets his sights on Yoko despite restaurant owner Ryoko’s (Mie Nakao) obvious desire to marry him and move to the country for a more simple life, but Yoko is more attracted to the oblivious Nakai, who soon finds himself in the middle of the president’s untoward relationship with the much younger, hot-to-trot cocktail hostess Beniko (Mie Hama). It all comes to a head as a pair of American tourists (Ernest and Marjorie Richter) and a prominent U.S. executive seek the right Japanese tourism company to do business with.

Japan Society’s 2016 Globus Film Series, “Japan Sings! The Japanese Musical Film,” opens April 8 with Eizo Sugawa’s riotous, robust 1964 delight, You Can Succeed, Too. With the Tokyo Summer Olympics approaching, Towa Tourism is locked in a heated battle with Kyokuto Tourism for big travel clients. While Yamakawa (Frankie Sakai) has developed a can’t-miss plan to succeed at Towa — either marry the president’s daughter, become a union leader, or find the president’s weakness and exploit it — his friend Nakai (Tadao Takashima) does not enjoy the urban rat race and would rather settle down in the countryside. When the president, Nobuo Kataoka (Yoshitomi Masuda), returns from a trip to the United States with his daughter, Yoko (Izumi Yukimura), he puts her in charge of the foreign office as she extolls the virtues of efficient American business practices over the old-fashioned Japanese ways. Yamakawa sets his sights on Yoko despite restaurant owner Ryoko’s (Mie Nakao) obvious desire to marry him and move to the country for a more simple life, but Yoko is more attracted to the oblivious Nakai, who soon finds himself in the middle of the president’s untoward relationship with the much younger, hot-to-trot cocktail hostess Beniko (Mie Hama). It all comes to a head as a pair of American tourists (Ernest and Marjorie Richter) and a prominent U.S. executive seek the right Japanese tourism company to do business with.