Chang-su (Kang Yoon-soo) fights off loneliness and desperation in Juichiro Yamasaki’s Yamabuki

YAMABUKI (Juichiro Yamasaki, 2022)

IFC Center

323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St.

Friday, February 10, 7:00, and Saturday, February 11, 4:00

Series runs February 10-16, $17

212-924-7771

www.ifccenter.com

yamabuki-film.com/en

“You have two options. Be prepared to die for what you believe or give up on it and run from it,” widowed detective Hayakawa (Yohta Kawase) tells his teenage daughter, Yamabuki (Kilala Inori), in Juichiro Yamasaki’s Yamabuki, making its US premiere February 10-11 at IFC as part of the sixth ACA Cinema Project series, “New Films from Japan.”

The first Japanese film selected for the ACID section at Cannes, Yamasaki’s third feature follows multiple characters as they struggle through the loneliness of everyday existence, their lives intertwining primarily at a crossroad intersection in a small town. It all takes place in Maniwa, where Yamasaki’s father was born and where Yamasaki is a tomato farmer in addition to being a writer and director.

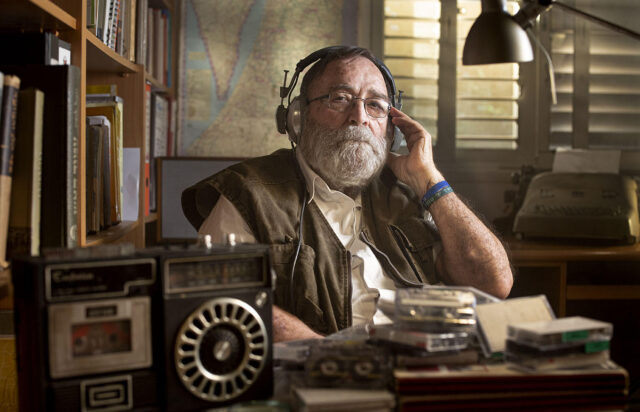

Chang-su (Kang Yoon-soo) is a former Olympic equestrian who had to quit the sport when his father’s business collapsed. The South Korean native is now working in Japan for a construction company that shatters large rock formations in a mountain quarry; the resulting gravel will be used to build infrastructure for the Tokyo Olympics. The soft-spoken Chang-su lives with his girlfriend, Minami (Misa Wada), and her six-year-old daughter, Uzuki, whose father is out of the picture.

Yamabuki is a high school student who spends much of her time “silent standing” at the crossroad with a small group, holding signs protesting the 2015 military legislation change that permitted Japan to get involved in foreign conflicts even when not for self-defense. She is joined by Yusuke (Hisao Kurozumi), a classmate who is obsessed with her; while her sign reads, “Flowers in the rifle barrel! Peace in Okinawa!,” his declares, “I’m in love with this woman!” with an arrow pointing at her.

On one of his mountain hikes, Hayakawa spots a small yamabuki plant, also known as the Japanese rose, and decides to take it home and replant it in his garden. However, while doing so, he dislodges numerous large stones of the type Chang-su smashes, and, without Hayakawa’s knowledge, they tumble down onto the mountain road where Chang-su is driving, causing him to get into an accident and break his leg. Shortly thereafter, something else falls down the mountain that leads the many subplots to intersect even further (while also offering another meaning of the word “yamabuki”).

Yamabuki (Kilala Inori) is not sure of her place in the world in Juichiro Yamasaki’s third feature

Yamabuki is shot on 16mm film stock by cinematographer Kenta Tawara, giving the movie a grainy, nostalgic feel; if it weren’t for the cars and the occasional use of cell phones, you might think it was made in the 1970s, especially when Chang-su stops twice to use public pay phones. Composer Olivier Deparis’s toy piano score adds to the film’s wistfulness while Sébastien Laudenbach’s animation of blossoming yamabukis in the opening and closing credits are charming, bookending the pervading melancholia.

The Osaka-born Yamasaki (The Sound of Light, Sanchu Uprising: Voice at Dawn) — who was inspired to make the film not only by the Olympics but because of Kang Yoon-soo’s real life as a Korean actor who moved to Maniwa with a woman and her two children — takes his time with the narrative; scenes unfold slowly, often with not much happening and explanation kept at a minimum, left to visual and aural poetry. “Di tang grows in the shade, where people don’t look,” a prostitute says to Hayakawa about a tree she spots through a window, surrounded by garbage. “Sunflowers face the sun but you don’t have to,” Yamabuki recalls her mother telling her.

The final moments of the film turn surreal and can be interpreted in several different ways. Oddly, much of the scene is used in the official trailer, so anyone wanting to see the film should avoid that at all costs.

Yamabuki is screening February 10 at 7:00 and February 11 at 4:00, with Yamasaki on hand for Q&As at each show. The series continues through February 16 with Kei Ishikawa’s A Man, Shô Miyake’s Small, Slow, and Steady, Nao Kubota’s Thousand and One Nights, and Yuji Nakae’s The Zen Diary.