Ron Heist shares his love of building in DOC NYC world premiere, Mole Man

MOLE MAN (Guy Fiorita, 2017)

Friday, November 10, Cinépolis Chelsea, 260 West Twenty-Third St. at Eighth Ave., 212-691-5519, $19, 7:30

Monday, November 13, IFC Center, 323 Sixth Ave. at West Third St., $12, 12:15

Festival runs November 9-16 (various passes $75-$750)

www.docnyc.net

www.facebook.com

After appearing on a 2010 episode of the History Channel series American Pickers, Ron Heist gained cult status for the massive structure he had been building in his parents’ large backyard in Butler, Pennsylvania, since 1965. The director of that episode, Guy Fiorita, has now made the bittersweet documentary Mole Man, a fascinating look inside the life and times of a unique man. Born in 1950, Ron has been obsessed with building things since he was a child. Now sixty-seven, toothless, and usually wearing a dark hoodie, Ron has constructed twenty-five buildings and twenty-three cellars linked by narrow passageways on his family’s property. He built it all by hand and by himself, scavenging items from more than seven hundred abandoned homes and factories, many of which had been left vacant following the closing of the Pullman Standard railcar plant in 1982. He refuses to use nails or mortar or even a level, relying on his own feel and intuition. He gets on his motorcycle, puts on his helmet, and meanders through the woods until he finds these houses, then brings back wood, doors, window frames, cinder blocks, chests, and whatever else he can fit on the back of his bike, as well as balls, plungers, clocks, license plates, and other items he collects. “People shouldn’t be as wasteful,” he says while showing off some treasures he has just found. Ron was always different, and his father, Chuck, treated him special; but the film’s real subject is Ron’s prospects: following the recent death of his father, Ron is left with his ninety-year-old mother, Mary, and his future becomes doubtful. The family, including Ron’s brother, Tim, and sister, Christine, who love Ron dearly, think that their mother would be better off in a smaller home, and they don’t have enough money to maintain the house. Meanwhile, they finally get Ron tested by a therapist to confirm that he has autism — he was previously diagnosed as “mentally challenged,” as were many of a lost generation of undiagnosed adults with the condition — and might be eligible for certain health benefits, although they worry about what might happen to Ron if he has to live elsewhere. “His routine, his environment . . . that’s his safety zone,” Tim says. But when Ron tells three of his friends, Sean Burke, Mike, and his cousin-in-law, John Burkert, that he knows where the Piney Mansion is, they believe they might find more than enough valuable objects, particularly some old, classic cars, to keep Ron living at home, so off into the woods they go, on a rather difficult journey. “To see Ron pulled out of that place, I think, would kill him, plain and simple,” John explains. “I just don’t think he’d want to live anymore.”

After appearing on a 2010 episode of the History Channel series American Pickers, Ron Heist gained cult status for the massive structure he had been building in his parents’ large backyard in Butler, Pennsylvania, since 1965. The director of that episode, Guy Fiorita, has now made the bittersweet documentary Mole Man, a fascinating look inside the life and times of a unique man. Born in 1950, Ron has been obsessed with building things since he was a child. Now sixty-seven, toothless, and usually wearing a dark hoodie, Ron has constructed twenty-five buildings and twenty-three cellars linked by narrow passageways on his family’s property. He built it all by hand and by himself, scavenging items from more than seven hundred abandoned homes and factories, many of which had been left vacant following the closing of the Pullman Standard railcar plant in 1982. He refuses to use nails or mortar or even a level, relying on his own feel and intuition. He gets on his motorcycle, puts on his helmet, and meanders through the woods until he finds these houses, then brings back wood, doors, window frames, cinder blocks, chests, and whatever else he can fit on the back of his bike, as well as balls, plungers, clocks, license plates, and other items he collects. “People shouldn’t be as wasteful,” he says while showing off some treasures he has just found. Ron was always different, and his father, Chuck, treated him special; but the film’s real subject is Ron’s prospects: following the recent death of his father, Ron is left with his ninety-year-old mother, Mary, and his future becomes doubtful. The family, including Ron’s brother, Tim, and sister, Christine, who love Ron dearly, think that their mother would be better off in a smaller home, and they don’t have enough money to maintain the house. Meanwhile, they finally get Ron tested by a therapist to confirm that he has autism — he was previously diagnosed as “mentally challenged,” as were many of a lost generation of undiagnosed adults with the condition — and might be eligible for certain health benefits, although they worry about what might happen to Ron if he has to live elsewhere. “His routine, his environment . . . that’s his safety zone,” Tim says. But when Ron tells three of his friends, Sean Burke, Mike, and his cousin-in-law, John Burkert, that he knows where the Piney Mansion is, they believe they might find more than enough valuable objects, particularly some old, classic cars, to keep Ron living at home, so off into the woods they go, on a rather difficult journey. “To see Ron pulled out of that place, I think, would kill him, plain and simple,” John explains. “I just don’t think he’d want to live anymore.”

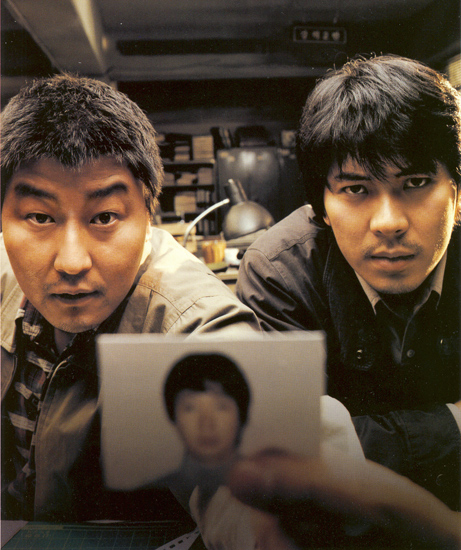

Mole Man Ron Heist picks up materials and brings them back home on his motorcycle

Ron is an endearing, eminently likable character. He has a childlike enthusiasm and even somewhat resembles a taller version of the Mole Men from the 1951 Superman film, although that’s not where he got his nickname from. “He loves being the Mole Man,” Burkert says. Like many people with autism, he has trouble holding conversations unless it’s on a subject that interests him, like time, numbers, construction, and scavenging. People naturally are drawn to his love of life and his dedication to his ever-expanding living quarters, although safety issues are a growing concern. Fiorita never exploits Ron, instead celebrating his individuality while also recognizing that Ron’s immediate future is at risk. Mole Man is having its world premiere at DOC NYC on November 10 and 13, with Fiorita, producers Cassidy Hartmann and James DeJulio, and some of the film’s subjects participating in postscreening Q&As. DOC NYC runs November 9 to 16 at Cinepolis Chelsea, the SVA Theatre, and IFC Center, with more than 150 features and shorts, by such documentarians as Barbara Kopple, Errol Morris, Laura Poitras, and Heidi Ewing and Rachel Grady; the films highlight such diverse figures as Eric Clapton, Curtis Sliwa, Lorraine Hansberry, Sammy Davis Jr., and David Bowie in addition to exploring many contemporary sociocultural issues from around the world.

I never went to boarding school, but if I had, I’d like it to have been at the Headfort School in Kells, County Meath, Ireland, which promises “an education that lasts a lifetime.” The institution, founded in 1949 in a two-hundred-year-old building, is highlighted in the extraordinarily enchanting documentary School Life. Director and cinematographer Neasa Ní Chianáin and director and producer David Rane focus on the daily exploits of husband and wife teachers John and Amanda Leyden, who have been at Headfort for more than forty-five years. The film follows them from their quaint house to their classrooms and special projects: John, tall and thin, with an acerbic wit and scraggly white hair on the back of his head, is putting together the school rock band, while Amanda, short and stout with an infectious enthusiasm for life, is staging Hamlet with a handpicked group of students. Headmaster Dermot Dix, who attended the school himself and had the Leydens as teachers, gives them a wide berth, and they are allowed to be themselves, questioning the existence of a supreme being and supporting same-sex marriage; in fact, everyone at Headfort, from the teachers to the students and the administrators, is encouraged to be themselves, rather than pigeonholed into standard, uniform expectations. Dix even considers it a place where students can “horse around” and “get mucky and muddy”; at one point John, who also teaches math and Latin, is outside in the forest, pushing one of the girls on a makeshift swing. Previously titled In Loco Parentis — “in place of parents” — when it was a hit at Sundance, School Life rarely shows any mothers or fathers, which is extremely refreshing in this age of helicopter parenting. Ní Chianáin (Fairytale of Kathmandu, The Stranger) also avoids talking heads, instead opting for a fly-on-the-wall style that puts us right in the middle of things, without so-called experts explaining to us what is happening and why it’s all so engaging.

I never went to boarding school, but if I had, I’d like it to have been at the Headfort School in Kells, County Meath, Ireland, which promises “an education that lasts a lifetime.” The institution, founded in 1949 in a two-hundred-year-old building, is highlighted in the extraordinarily enchanting documentary School Life. Director and cinematographer Neasa Ní Chianáin and director and producer David Rane focus on the daily exploits of husband and wife teachers John and Amanda Leyden, who have been at Headfort for more than forty-five years. The film follows them from their quaint house to their classrooms and special projects: John, tall and thin, with an acerbic wit and scraggly white hair on the back of his head, is putting together the school rock band, while Amanda, short and stout with an infectious enthusiasm for life, is staging Hamlet with a handpicked group of students. Headmaster Dermot Dix, who attended the school himself and had the Leydens as teachers, gives them a wide berth, and they are allowed to be themselves, questioning the existence of a supreme being and supporting same-sex marriage; in fact, everyone at Headfort, from the teachers to the students and the administrators, is encouraged to be themselves, rather than pigeonholed into standard, uniform expectations. Dix even considers it a place where students can “horse around” and “get mucky and muddy”; at one point John, who also teaches math and Latin, is outside in the forest, pushing one of the girls on a makeshift swing. Previously titled In Loco Parentis — “in place of parents” — when it was a hit at Sundance, School Life rarely shows any mothers or fathers, which is extremely refreshing in this age of helicopter parenting. Ní Chianáin (Fairytale of Kathmandu, The Stranger) also avoids talking heads, instead opting for a fly-on-the-wall style that puts us right in the middle of things, without so-called experts explaining to us what is happening and why it’s all so engaging.

In 2006, South Korean writer-director Bong Joon-ho burst onto the international cinematic landscape with the sleeper hit The Host, a modern-day monster movie with a lot of heart. He followed that up with the touching segment “Shaking Tokyo” in the compilation film

In 2006, South Korean writer-director Bong Joon-ho burst onto the international cinematic landscape with the sleeper hit The Host, a modern-day monster movie with a lot of heart. He followed that up with the touching segment “Shaking Tokyo” in the compilation film