CINÉSALON: YOYO (Pierre Étaix, 1965)

French Institute Alliance Française, Florence Gould Hall

55 East 59th St. between Madison & Park Aves.

Tuesday, February 3, 4:00

Series continues Tuesdays through February 24

212-355-6100

www.fiaf.org

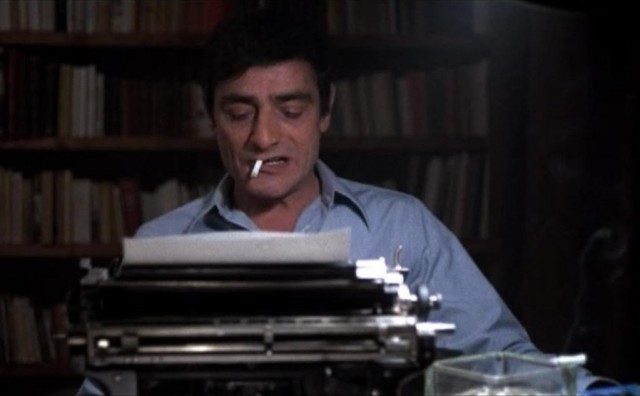

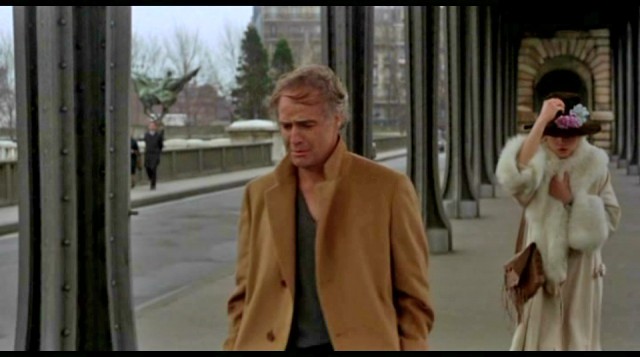

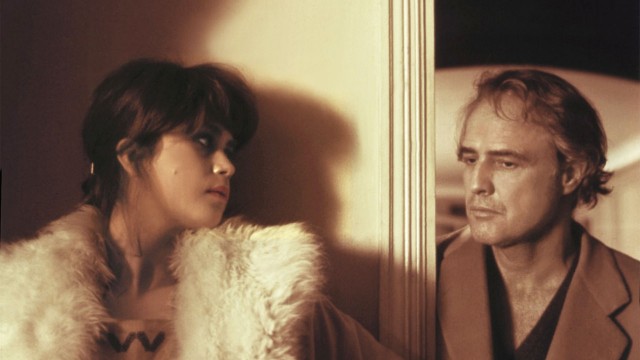

French auteur Pierre Étaix’s strange and beautiful films were long inaccessible, the subject of nearly two decades of legal wrangling, but on February 3 at 4:00, the French Institute Alliance Française will be presenting his 1965 bittersweet black-and-white slapstick charmer, Yoyo, as part of its January-February CinéSalon “Eccentrics of French Comedy” series, followed by a wine reception. (In April 2010, Étaix was finally able to once again bring his films to the public, his entire output restored and making their New York debut at a festival of all five features and three shorts at Film Forum in October 2012.) Étaix, who wrote Yoyo with master collaborator Jean-Claude Carrière, who also cowrote films by Luis Buñuel, Miloš Forman, Volker Schlöndorff, Andrzej Wajda, Nagisa Oshima, and Louis Malle and won an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement in 2014, stars as a ridiculously wealthy but extremely bored man who lives alone in an ornately decorated, absurdly large chateau. It’s 1925, and he has servants for absolutely everything, as well as his own private band and flappers, but he pines for his lost love, Isolina (Claudine Auger). One day she arrives with a traveling circus, along with a young boy (Philippe Dionnet) who turns out to be his son. She at first rejects the multimillionaire, but when he loses it all on Black Tuesday, the three of them form their own traveling circus, with the boy ultimately turning into a popular clown named Yoyo (played as an adult by Étaix) and seeking to restore the chateau and his family.

French auteur Pierre Étaix’s strange and beautiful films were long inaccessible, the subject of nearly two decades of legal wrangling, but on February 3 at 4:00, the French Institute Alliance Française will be presenting his 1965 bittersweet black-and-white slapstick charmer, Yoyo, as part of its January-February CinéSalon “Eccentrics of French Comedy” series, followed by a wine reception. (In April 2010, Étaix was finally able to once again bring his films to the public, his entire output restored and making their New York debut at a festival of all five features and three shorts at Film Forum in October 2012.) Étaix, who wrote Yoyo with master collaborator Jean-Claude Carrière, who also cowrote films by Luis Buñuel, Miloš Forman, Volker Schlöndorff, Andrzej Wajda, Nagisa Oshima, and Louis Malle and won an honorary Academy Award for lifetime achievement in 2014, stars as a ridiculously wealthy but extremely bored man who lives alone in an ornately decorated, absurdly large chateau. It’s 1925, and he has servants for absolutely everything, as well as his own private band and flappers, but he pines for his lost love, Isolina (Claudine Auger). One day she arrives with a traveling circus, along with a young boy (Philippe Dionnet) who turns out to be his son. She at first rejects the multimillionaire, but when he loses it all on Black Tuesday, the three of them form their own traveling circus, with the boy ultimately turning into a popular clown named Yoyo (played as an adult by Étaix) and seeking to restore the chateau and his family.

The first section of the film is a glorious homage to the silent film era and other cinematic comedians, with director and star Étaix evoking his mentor, Jacques Tati; Charlie Chaplin; Buster Keaton; and, later, Jerry Lewis, with whom he’d appear as Gustav the Great in Lewis’s never-to-be-seen Holocaust film The Day the Clown Died. Nouvelle Vague cinematographer Jean Boffety (An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge; Je t’aime, je t’aime) shoots Yoyo in a sharp, gorgeous black-and-white, composing breathtaking shots that boast a dazzling symmetry that must make Wes Anderson giddy with delight, while Étaix fills the film with ingenious sight gags that would make Ernie Kovacs proud (just wait till you see the supposed still-life painting), all anchored by Jean Paillaud’s memorable musical theme. But once the stock market crashes and talkies take over, dialogue enters the picture, and the camera is often off balance, the perfect symmetry a thing of the past. With Yoyo, Étaix, who had previously made Heureux Anniversaire and The Suitor and would go on to make The Great Love and En pleine forme, was influenced by the sudden, tragic death of his father, his love of the circus — he had already worked under the big tent, and he would leave films to become a clown in a traveling circus in the early 1970s — and his viewing of Fellini’s 8½ (look for the La Strada poster) resulting in a film that sometimes gets a little lost and too surreal, but he ultimately brings things back around as Yoyo grows into a star and the story travels through the arc of twentieth-century entertainment, from the silent era to talkies to television. It’s a real treat that Étaix’s work is undergoing this rediscovery; lovers of Michel Hazanavicius’s The Artist will particularly enjoy Yoyo. “Eccentrics of French Comedy” continues through February 24 with Riad Sattouf’s The French Kissers introduced by Jean-Philippe Tessé, Jacques Rozier’s Du côté d’Orouët introduced by Annie Bergen, Eric Rohmer’s The Tree, the Mayor and the Mediatheque introduced by Nicholas Elliott, and Luc Moullet’s The Land of Madness introduced by Pavol Liska.

Back in October, a

Back in October, a