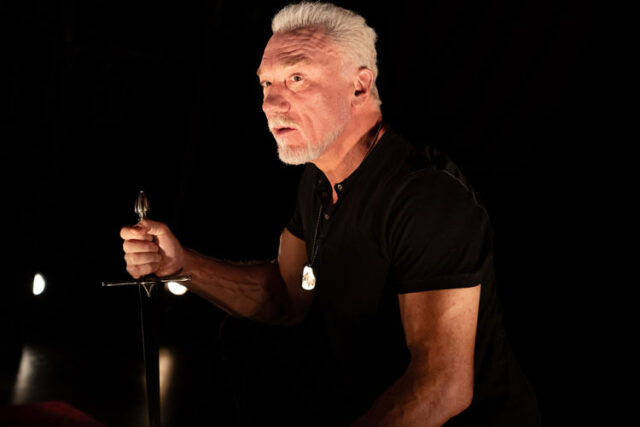

Dina Stevens (Mia Barron) involves Boubs (Abubakr Ali) in a complicated government plot as Y2K approaches (photo by Matthew Murphy)

DAKAR 2000

Manhattan Theatre Club

New York City Center Stage 1

Tuesday – Sunday through March 23, $79-$99

www.manhattantheatreclub.com

www.nycitycenter.org

“If we both describe the same thing at the same time, will one of our descriptions be more true than the other?” Isaac says to Nikolai in Rajiv Joseph’s 2017 time-leaping play Describe the Night. Later, Feliks tells Mariya, “You love to make up stories that are more interesting than what the truth is.”

The concept of “the truth” is also central to Joseph’s latest work, Dakar 2000, a gripping cat-and-mouse contemporary noir presented by Manhattan Theatre Club at New York City Center’s Stage 1 through March 23.

It’s December 31, 2024, and a fifty-year-old man (Abubakr Ali) walks onstage and delivers a monologue detailing a series of life-altering events that happened to him twenty-five years earlier, during the last few days leading up to Y2K, when some people thought the world might end.

Standing on a swirling ramp, he begins, “This is a story within a story, about a person within a person, in a time within another time. In a galaxy far, far away. All of it . . . is true. Or most of it, anyway. Names have been changed. Some of the places have been changed. Some of the boring parts snipped away. Some other stuff has been added to make it . . . theoretically more interesting. But otherwise all of it is almost entirely true.”

After telling us about a secret job he had that has taken him across the globe, he concludes, “The truth — the dumb, boring truth — is that this is mostly the story of a kid who just wanted to make a difference. And the truth is . . . he didn’t. I mean, I didn’t. Or I hadn’t . . . I hadn’t done much of any consequence, ever. Until I flipped my truck, just before the millennium . . . And met a woman who worked at the State Department.”

The narrative shifts to late December 1999, and Boubacar (Ali), known as Boubs (pronounced “boobs”), is a Peace Corps volunteer in Senegal, stationed in Kaolack and building a fenced-in community garden in the nearby village of Thiadiaye. Sporting a bandage around his injured head following the accident, he has been called in to meet with Dina Stevens (Mia Barron), who identifies herself as the Deputy Regional Supervisor of Safety & Security for Sub-Saharan Africa. Dina watches Boubs carefully as he shares the details of what led to the crash; she then starts asking pointed questions that tear holes in his story. He keeps up what turns out to be a ruse until she accuses him of lying about his situation, and he ultimately admits to repurposing materials that were meant for other projects.

Threatening to send him back home to America, Dina, who is hell bent on avenging the murder of several of her friends in the 1998 embassy bombing in Tanzania, offers Boubs the option of performing an odd task for her instead, which leads to another task, and another, each one more mysterious and perilous — and bringing Boubs and Dina closer and closer. As Y2K approaches, Boubs doesn’t know what to believe, and neither does the audience.

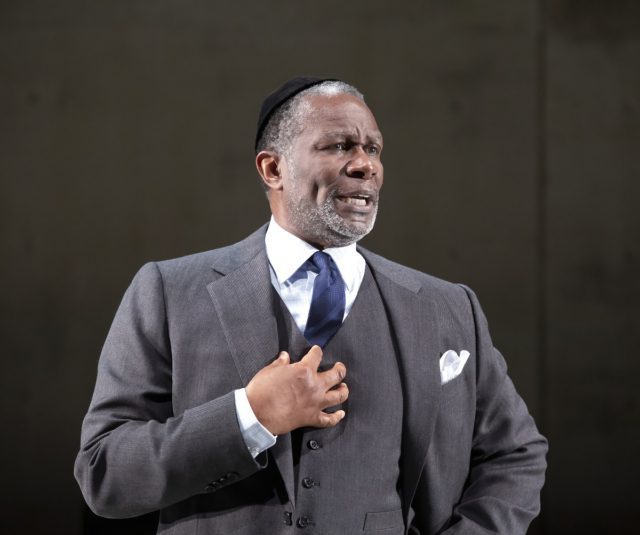

Boubs (Abubakr Ali) and Dina Stevens (Mia Barron) grow close working together in Rajiv Joseph’s Dakar 2000 (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Dakar 2000 is a riveting thriller reminiscent of Stanley Donen’s 1963 Hitchcockian favorite Charade, in which Audrey Hepburn stars as an American expat unexpectedly caught up in a dangerous spy drama in Paris after her husband is killed and she is pursued by multiple men, one of whom (Cary Grant) claims he is trying to help her even though she catches him in lie after lie. Which is not to say that Barron and Ali have the same kind of chemistry as Hepburn and Grant, but the quirky relationship between Dina and Boubs is appealing. At one point, when they’re on Boubs’s roof, face-to-face, you want them to kiss but also want them not to, as neither one is ultimately trustworthy.

Two-time Obie winner Rajiv Joseph (Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo, King James) and director May Adrales (Vietgone, Poor Yella Rednecks) keep us guessing all the way to the finale. Tim Mackabee’s turntable set moves from Dina’s office and a restaurant to the roof and a hotel bedroom, with small props occasionally surreptitiously added when it rotates from scene to scene. Shawn Duan’s projections range from a starry sky and outdoor African locations to text that establishes the precise time and location. A metaphor linking the 1997 Hale Bopp Comet to fate is confusing, but the choice of Culture Club’s 1983 hit “Karma Chameleon” as the song connecting Boubs with his ex-girlfriend is inspired, with Boy George singing, “There’s a loving in your eyes all the way / If I listen to your lies, would you say / I’m a man without conviction / I’m a man who doesn’t know / How to sell a contradiction / You come and go, you come and go.”

Ever-dependable Obie winner Barron (The Coast Starlight, Dying for It) effectively captures Dina’s enigmatic nature, representing an unethical government that holds all the cards. Ali (Toros) portrays Boubs’s younger self with a tender vulnerability that makes his actions understandable, although his overall characterization is ultimately a bit uneven, his voice too often switching pitches, his youth making him less than convincing as the modern-day Boubs.

Joseph has noted that Dina and Ali are based on actual people, but that doesn’t mean Dakar 2000 is a documentary play, particularly as words such as truth and lie show up over and over again. During the course of the work’s brisk eighty minutes, Dina tells Boubs, “You’re a good liar,” “Trust me, I wouldn’t lie to you about this,” and “Do you ever wonder if it’s all a big lie?” Meanwhile, Boubs wonders, “How could it be a lie?” when Dina questions humanity’s general consciousness.

Theater by its very definition presents a fictional version of reality, no matter how factual it might be. But in the case of Dakar 2000 and other plays by Joseph, we should be grateful that he “loves to make up stories that are more interesting than what the truth is.”

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]