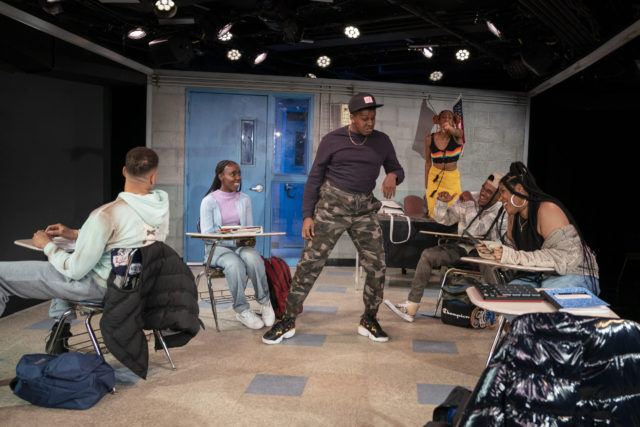

Detention turns existential in new play by Dave Harris (photo by Joan Marcus)

EXCEPTION TO THE RULE

Black Box Theatre

Harold and Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre

111 West 46th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday/Wednesday – Sunday through June 26, $30

www.roundabouttheatre.org

The Breakfast Club meets Waiting for Godot and Five Characters in Search of an Exit in Dave Harris’s electric Exception to the Rule, which opened tonight at Roundabout Underground. Originally meant to mark Harris’s New York debut but delayed because of the pandemic, Exception now follows on the heels of the breakout success of Tambo & Bones, which was written after Exception.

The eighty-five-minute play takes place in a classroom open on three sides, with six chairs in addition to the teacher’s desk next to the door. The room has fluorescent borders, making it resemble a cage with no bars, a kind of existential prison. The audience sits on the three open sides in three rows, the first nearly on the set, as if on the brink of being jailed as well but just safe enough. One by one, five high school teenagers unabashedly enter and kid around with one another. They are there for detention, something they appear to be used to. Tommy (Malik Childs) puts the moves on Mikayla (Amandla Jahava), who wants nothing to do with him. The tough-looking Dayrin (Toney Goins) calls Dasani (Claudia Logan) “Aquafina” and “Poland Springs” to piss her off. Dayrin is none-too-happy when the moody Abdul (Mister Fitzgerald) shows up. But the freewheeling dynamic shifts immediately when Erika (Mayaa Boateng) arrives, looking for Mr. Bernie, the detention teacher. The others are shocked that she has been sent to Room 111.

“I never thought I’d see the day,” Dasani says. “How did she end up in detention?” Mikayla asks. “You sure she supposed to be here?” Tommy says to Mikayla. “Every good girl gotta go bad at some point,” Dayrin offers.

Erika is dismayed by all the attention she is receiving as they derisively refer to her as “Smart Girl Erika,” “College Bound Erika,” and “Take the Test and Fuck Up the Curve for Everybody Else Erika.” She explains, “I thought detention was quiet. A place where everyone remembers the mistakes that got them here and then learns how to not make the same mistakes again. And you leave different than when you came in. Why else would they put you here?” After a brief silence, the others break out in hysterics.

“You might be the only person left in this school who’s never done some time,” Abdul says. “Still haven’t lost your innocence yet,” Dayrin adds.

College-bound Erika (Mayaa Boateng) makes a connection with Abdul (Mister Fitzgerald) in Exception to the Rule (photo by Joan Marcus)

As they wait for Mr. Bernie — if they don’t get their detention slips signed, they’ll receive more detention — the six teenagers bond, argue, fight, flirt, and reveal secrets about themselves, each trapped in a system set up for them to fail. They’re terrified just to go into the hall to find Mr. Bernie. “I heard this kid Roger left detention one time. You know what they did? They shot him on sight. He dead,” Tommy says. As apocryphal as that story might be, it holds the awful truth of what happens to so many innocent, unarmed people of color.

Meanwhile, there’s no cell service in Room 111 or anywhere in the school. Tommy points out, “Phones can’t even tell what time it is. Cuz the whole building is surrounded by an invisible force to keep us from calling for any —” Time, for Black and brown people, is a weighted concept; the more things change, the more they stay the same.

Intermittent announcements over the creaky PA remind them that it’s the Friday afternoon of the MLK holiday weekend and the school will be closed for the next three days, leading Dasani to reinterpret Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech for what is happening today; it’s one of the most powerful moments of a play constructed of myriad small touches that can nearly go unnoticed. Director Miranda Haymon always has something going on; the audience has to keep their eyes moving to catch everything, and you won’t want to miss a second of these well-crafted characters and potent situations as the clock winds down and the six teens have to make critical choices.

In Tambo & Bones, Harris investigated the history of Black performers entertaining paying white audiences, but it’s much more than a treatise on minstrelsy. While Bones wants to cash in, draping himself in stardom, Tambo wants to help change the world. In Exception to the Rule, takes on social injustice, inequities in education and employment, and a corrupt system that is rotten to the core, but he is also making it clear that there are ways out. Erika is a stand-in for the playwright, who pulls no punches. She’s a top student preparing for college, getting ridiculed for her desire to succeed; some of the others occasionally look like they also want to be better students with more opportunities, but that is frowned upon by their peers. Even their outfits — the costumes are by Sarita Fellows — play with stereotypes and expectations.

Six characters are in search of an exit in Roundabout Underground world premiere (photo by Joan Marcus)

Reid Thompson and Kamil James’s dynamic set seems to offer them an escape, as if they can just walk through the invisible bars and into another world, but that’s not something they’re considering; they’re scared enough of going through an unlocked door into a situation they’re already familiar with. “There’s no one keeping us in this room,” Erika says. Dasani responds, “We in detention. We gotta wait for Mr. Bernie. Then we can go, Sweet Pea. Then we can go.” It’s as if society has relegated them to an unending prison, where it doesn’t matter what they’ve done; they can’t even imagine being free.

The outstanding cast bursts with an energy that can barely be contained on the set; in fact, one fight nearly spilled into the audience (but didn’t), making the action all the more palpable and realistic.

Cha See’s lighting keeps the audience at least partly illuminated throughout the play; it is not lost on us, or the actors and playwright, that the crowd is predominantly white, watching six caged people of color. No wonder they are hesitant to walk through the invisible bars. But Harris is adamant that they must, that in order to better their lives, they need to go forward, to face what’s out there and not let the system, as well as cultural norms, hold them back. Tommy might be afraid of the dark, but there’s light ahead.

“Just imagine. If life was all tingly and nice. . . . If closing my eyes was just closing my eyes,” Tommy says. Erika replies, “You’d still be in detention when you opened them.”