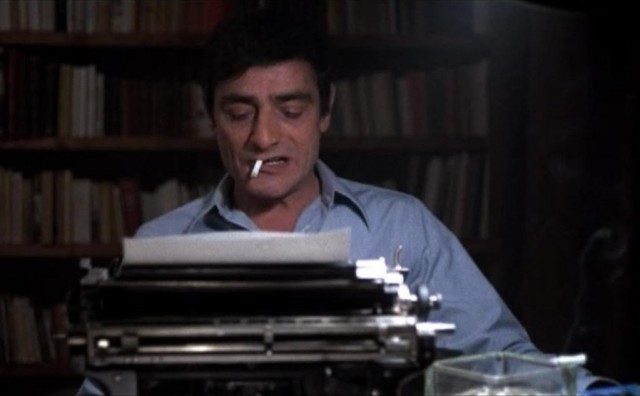

Lisette (Paulette Dubost) and Christine (Nora Grégor) discuss love and fidelity in Jean Renoir masterpiece

CinéSalon: THE RULES OF THE GAME (LA RÈGLE DU JEU) (Jean Renior, 1939)

French Institute Alliance Française, Florence Gould Hall

55 East 59th St. between Madison & Park Aves.

Tuesday, May 5, $13, 4:00 & 7:30

Festival runs through May 26

212-355-6100

www.fiaf.org

“We’ll have as much fun as we can,” Robert de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) says in Jean Renoir’s 1939 comic masterpiece, the madcap farce The Rules of the Game. And oh, what fun it is. Renoir, the son of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, skewers love and lust among France’s idle rich on the eve of WWII, the haute bourgeoisie fiddling in their own self-defeating way while their country is about to burn. Banned by the government for being “too demoralizing,” The Rules of the Game follows a group of men and women, both servants and masters, as they jump from bed to bed, sometimes in full view of their spouse. It’s 1939, but even with war on the horizon, a fanciful coterie of friends and acquaintances have gathered for a weekend at Château de la Colinière, the country estate owned by Robert, who is married to Christine (Nora Grégor) but has been fooling around with Geneviève de Marras (Mila Parély). Christine, meanwhile, is being wooed by aviator André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who has just flown solo across the Atlantic, and the dapper Monsieur de St. Aubin (Pierre Nay). Newly hired domestic Marceau (Julien Carette) has the hots for Christine’s maid, Lisette (Paulette Dubost), whose extremely jealous husband, Edouard Schumacher (Gaston Modot), is Robert’s game warden, prowling the grounds with a rifle he is ready to use. And in the middle of it all is Octave (Renoir), a bear of man who is friends with André and Christine and a former lover of Lisette’s. Borrowing elements from Alfred de Musset’s Les caprices de Marianne and Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro, Renoir depicts French society as a bunch of silly, selfish fools, and even though in the credits, over delightful music by Mozart, he calls it “A Dramatic Fantasy” that “does not claim to be a study of manners,” he later referred to it as “an exact description of the bourgeoisie of our time.” Its truthfulness is what helped make the film a critical and popular failure upon its initial release, leading Renoir to cut nearly a half hour in a desperate attempt to save it.

“We’ll have as much fun as we can,” Robert de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) says in Jean Renoir’s 1939 comic masterpiece, the madcap farce The Rules of the Game. And oh, what fun it is. Renoir, the son of Impressionist painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir, skewers love and lust among France’s idle rich on the eve of WWII, the haute bourgeoisie fiddling in their own self-defeating way while their country is about to burn. Banned by the government for being “too demoralizing,” The Rules of the Game follows a group of men and women, both servants and masters, as they jump from bed to bed, sometimes in full view of their spouse. It’s 1939, but even with war on the horizon, a fanciful coterie of friends and acquaintances have gathered for a weekend at Château de la Colinière, the country estate owned by Robert, who is married to Christine (Nora Grégor) but has been fooling around with Geneviève de Marras (Mila Parély). Christine, meanwhile, is being wooed by aviator André Jurieux (Roland Toutain), who has just flown solo across the Atlantic, and the dapper Monsieur de St. Aubin (Pierre Nay). Newly hired domestic Marceau (Julien Carette) has the hots for Christine’s maid, Lisette (Paulette Dubost), whose extremely jealous husband, Edouard Schumacher (Gaston Modot), is Robert’s game warden, prowling the grounds with a rifle he is ready to use. And in the middle of it all is Octave (Renoir), a bear of man who is friends with André and Christine and a former lover of Lisette’s. Borrowing elements from Alfred de Musset’s Les caprices de Marianne and Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s Le mariage de Figaro, Renoir depicts French society as a bunch of silly, selfish fools, and even though in the credits, over delightful music by Mozart, he calls it “A Dramatic Fantasy” that “does not claim to be a study of manners,” he later referred to it as “an exact description of the bourgeoisie of our time.” Its truthfulness is what helped make the film a critical and popular failure upon its initial release, leading Renoir to cut nearly a half hour in a desperate attempt to save it.

André Jurieux (Roland Toutain) and Robert de la Chesnaye (Marcel Dalio) fight over Robert’s wife in THE RULES OF THE GAME

“It is a war film, and yet there is no reference to the war,” Renoir wrote in his 1974 memoir, My Life and My Films. “Beneath its seemingly innocuous appearance the story attacks the very structure of our society. Yet all I thought about at the beginning was nothing avant-garde but a good little orthodox film. People go to the cinema in the hope of forgetting their everyday problems, and it was precisely their own worries that I plunged them into. The imminence of war made them even more thin-skinned. I depicted pleasant, sympathetic characters, but showed them in a society in process of disintegration, so that they were defeated at the outset, like Stahremberg and his peasants. The audience recognized this. The truth is they recognized themselves. People who commit suicide do not care to do it in front of witnesses. I was utterly dumbfounded when it became apparent that the film, which I wanted to be a pleasant one, rubbed most people up the wrong way.” The Rules of the Game was ultimately restored and reevaluated in 1959, being justly recognized as a misunderstood classic. Renoir and cinematographer Jean Bachelet use deep focus, long scenes, and carefully orchestrated close-ups to comment on luxury and class, brilliantly using metaphor as a storytelling device, particularly during the hunting scene at the château. The militaristic Shumacher is determined to catch the poor, disheveled Marceau poaching rabbits — first those sexually active animals on the grounds of the estate, then Shumacher’s wife inside. As the wealthy men and women fire at the rabbits, as well as pheasants, Renoir doesn’t turn the camera away, instead showing the creatures dying as the hunters cheer their success. It’s a painful scene to watch in a film otherwise filled with inventive slapstick and mayhem. It’s no wonder the French public initially booed the picture, which was essentially a rather unflattering mirror placed before their very eyes.

The Rules of the Game is one of the most important, and most entertaining, films ever made about love and class, about the relationships between the rich and the poor, both personal and professional. It’s no coincidence that it is Octave, played by writer-director Renoir himself, who says, “This world has rules — very strict rules,” which Renoir (Grand Illusion, Boudu Saved from Drowning) then tears down. The film still feels fresh and alive today, no mere museum piece, part “Love Stinks” by the J. Geils Band (“You love her / but she loves him / and he loves somebody else / you just can’t win”), part Upstairs, Downstairs, devastatingly funny and devilishly playful. And look for genre-redefining photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson as the English servant. Coco Chanel designed the dazzling “robes de la maison,” making The Rules of the Game a worthy selection for the French Institute Alliance Française CinéSalon series “Haute Couture on Film,” part of the larger “Fashion at FIAF” festival, where it is screening May 5 at 4:00 & 7:30; both presentations will be followed by a wine reception, and journalist Anne-Katrin Titze will introduce the later show. The series continues through May 26 with such other films as Jean Negulesco’s How to Marry a Millionaire and Luis Buñuel’s Belle de jour. The third annual “Fashion at Fiaf” also includes talks with Kate Betts and Garance Doré and a gallery exhibit of the work of photographer Grégoire Alexandre.

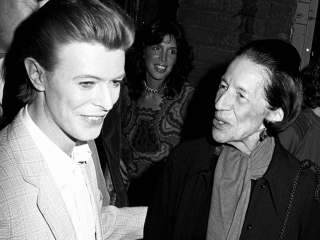

“There’s not many people like her. She’s unique,” photographer David Bailey says about his former boss, Diana Vreeland, in the DVD extras of the wonderful documentary Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel. “You could easily put her in a list of people like Cocteau and, in a funny sort of way, Proust. She was very Proustian in a way. She loved the detail of things, the memory of things,” he adds. The 2011 film, directed and produced by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who is married to Diana Vreeland’s grandson Alexander, and codirected and edited by Bent-Jorgen Perlmutt (Havana Motor Club) and Frédéric Tcheng (

“There’s not many people like her. She’s unique,” photographer David Bailey says about his former boss, Diana Vreeland, in the DVD extras of the wonderful documentary Diana Vreeland: The Eye Has to Travel. “You could easily put her in a list of people like Cocteau and, in a funny sort of way, Proust. She was very Proustian in a way. She loved the detail of things, the memory of things,” he adds. The 2011 film, directed and produced by Lisa Immordino Vreeland, who is married to Diana Vreeland’s grandson Alexander, and codirected and edited by Bent-Jorgen Perlmutt (Havana Motor Club) and Frédéric Tcheng (

Back in October, a

Back in October, a