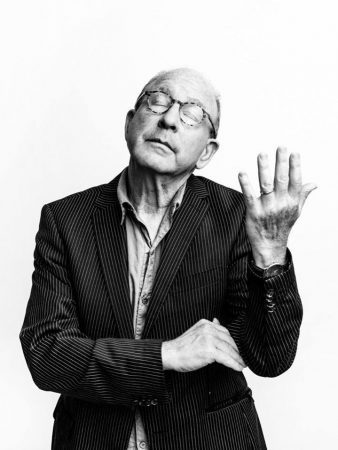

Jerry Saltz will discuss his new book and the state of art during the age of corona in live online conversation (photo courtesy Jerry Saltz)

Who: Jerry Saltz, Barbara Pollack, Anne Verhallen

What: Book and art talk with Jerry Saltz

Where: Livestream (email info@artatatimelikethis for password)

When: Friday, April 17, free, 4:00

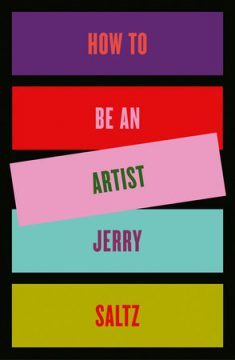

Why: Rock star art critic Jerry Saltz’s latest book has come along at just the right moment. How to Be an Artist (Riverhead Books, March 2020, $22) guides you through the creation of art — by anyone, regardless of talent and skill — espousing a dedicated work ethic, something that many of us are paradoxically demonstrating more than ever now that we’re stuck at home. “I have tried every way in the world to stop work-block or fear of working, of failure. There is only one method that works: work. And keep working,” Saltz, the Pulitzer Prize-winning senior art critic for New York magazine, writes in the book. “Every artist and writer I know claims to work in their sleep. I do all the time. Jasper Johns famously said, ‘One night I dreamed that I painted a large American flag, and the next morning I got up and I went out and bought the materials to begin it.’ How many times have you been given a whole career in your dreams and not heeded it? It doesn’t matter how scared you are; everyone is scared. Work. Work is the only thing that takes the curse of fear away.”

On March 17, Barbara Pollack and Anne Verhallen launched Art at a Time Like This, a website that features the work of a different artist every weekday, focusing on the question “How can you think of art at a time like this?” Among the participating artists are Ai Weiwei, Mickalene Thomas, Jacolby Satterwhite, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Dread Scott & Jenny Pollak, Marilyn Minter, and Dan Perjovschi, presenting new and older paintings, photographs, and videos, all of which illuminate in some way the crisis we are facing together, the onslaught of Covid-19, which has shut down galleries and museums around the world.

A social media icon, Saltz will join Pollack and Verhallen on April 17 at 4:00 for a live online conversation about the state of art on a planet in lockdown. “Jerry Saltz is a natural for livestream because he is the completely accessible art critic, dedicated to reaching all kinds of art lovers, from the aficionado to the art-curious,” Pollack told twi-ny. “His new book puts forth the insane idea that anyone can be an artist, or at least artistic. Of course, people love him for this!”

As someone who has been writing about art for nearly twenty years, I’ve been forced to reconsider how we all experience art during this pandemic, looking at it onscreen, right next to Facebook, Google, and my day-job site. Obviously it’s not the same, and I have to admit I at first had trouble adjusting, but I’m getting more used to it every day. But can you critique a work of art you’ve seen only online, not in person? When viewed in real life, you can sense a painting’s texture, its physical presence; a photograph can envelop you and shake your surroundings loose; and videos can beam out from unique sculptural installations. But when is the next time any of us is likely to step foot in a gallery or museum in the five boroughs (or elsewhere)? What will things be like once they do reopen? Will crowds descend on MoMA and the Met like they did before corona?

In his October review of the new MoMA for New York magazine, a piece entitled, “What Does the New MoMA Mean for Modernism? And What Was Modernism Anyway?,” Saltz wrote, “Here’s how art has already moved on. Modernism is now just part of art history to artists, and not even the only or best part.” How will art move on after Covid-19? What will become part of art history? I can’t wait to hear what Saltz has to say about what will become of art’s future.

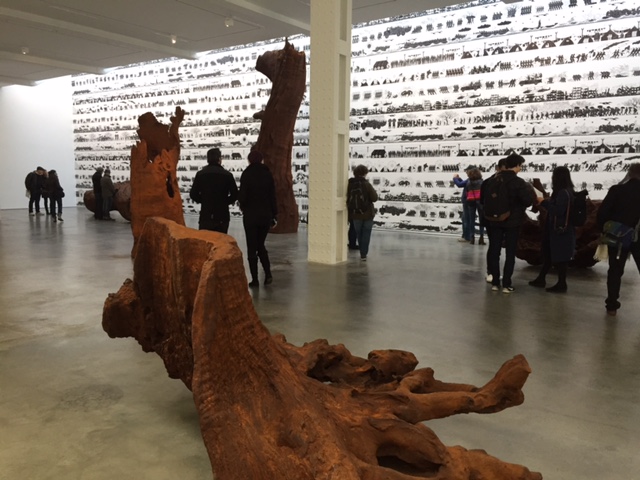

On January 3, Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei will travel from Manhattan to Brooklyn, participating in two Q&As following screenings of his stunning new documentary, Human Flow. This past fall, Ai had several concurrent exhibitions in New York City that dealt with the international refugee crisis. At Deitch Projects in SoHo,

On January 3, Chinese dissident artist Ai Weiwei will travel from Manhattan to Brooklyn, participating in two Q&As following screenings of his stunning new documentary, Human Flow. This past fall, Ai had several concurrent exhibitions in New York City that dealt with the international refugee crisis. At Deitch Projects in SoHo,