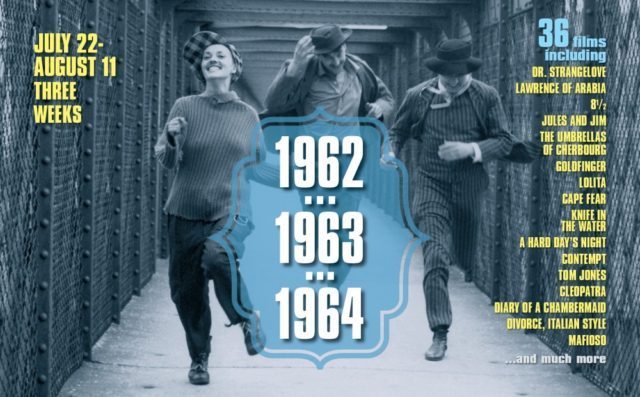

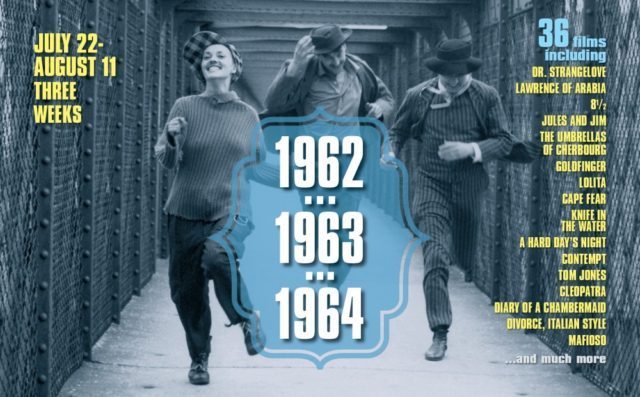

“1962 . . . 1963 . . . 1964”

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

July 22 – August 11

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

The years 1962, 1963, and 1964 were like no others in the history of America, and that evolving zeitgeist was captured on celluloid as the Hollywood studio system faded away. Film Forum is celebrating those three years with “1962 . . . 1963 . . . 1964,” a three-week series consisting of thirty-five cinematic works that, together, form a fascinating time capsule of the era. There are films by François Truffaut, David Lean, Stanley Kubrick, John Ford, Agnès Varda, Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini, Francis Ford Coppola, Alfred Hitchcock, Luis Buñuel, Sergio Leone, and many others, in multiple genres, with superstars ranging from Clint Eastwood, Marcello Mastroianni, and Sean Connery to Peter Sellers, Paul Newman, and the Fab Four.

The July 22 screening of Lolita will have a special prerecorded introduction from film critic and historian Stephen Farber. Below are select reviews from the festival, which is being held in conjunction with the Jewish Museum exhibition “New York: 1962-1964” and Film at Lincoln Center’s “New York, 1962-1964: Underground and Experimental Cinema.”

A young hitchhiker (Zygmunt Malanowicz) throws a kink in a couple’s sailing plans in Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water

KNIFE IN THE WATER (NÓŻ W WODZIE) (Roman Polanski, 1962)

Saturday, July 23, 5:10, and Monday, July 25, 6:20

filmforum.org

“Even discounting wind, weather, and the natural hazards of filming afloat, Knife in the Water was a devilishly difficult picture to make,” immensely talented and even more controversial Roman Polanski wrote in his 1984 autobiography, Roman by Polanski. That is likely to have been a blessing in disguise, upping the ante in the Polish filmmaker’s debut feature film, a tense three-character thriller set primarily on a sailboat, filmed on location. Upper-middle-class couple Andrzej (theater veteran Leon Niemczyk) and Krystyna (nonprofessional actor Jolanta Umecka) are on their way to their sailboat at the marina when a young hitchhiker (drama school grad Zygmunt Malanowicz) forces them to pull over on an otherwise empty road. Andrzej and the unnamed man almost immediately get involved in a physical and psychological pissing contest, with Andrzej soon inviting him to join them on their sojourn, practically daring the hitchhiker to make a move on his wife.

Once on the boat, the two men continue their battle of wills, which becomes more dangerous once the young man reveals his rather threatening knife, which he handles like a pro. Lodz Film School graduate Polanski, who collaborated on the final screenplay with Jerzy Skolimowski (The Shout, Moonlighting) after initially working with Jakub Goldberg, envelops the black-and-white Knife in the Water — the first Polish film to be nominated for a Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and winner of the Critics’ FIPRESCI Prize at the 1962 Venice Film Festival — in a highly volatile, claustrophobic energy, creating gorgeous scenes intimately photographed by cinematographer Jerzy Lipman, from Andrzej and Krystyna in their small car to all three trying to find space on the boat amid the vast sea and a changing wind. Many of the shots are highlighted by deep focus in which one character is shown in close-up in the foreground with the others in the background, alerting the viewer to various potential conflicts — sexual, economic, class- and gender-based — all underscored by Krzysztof T. Komeda’s intoxicating jazz score featuring saxophonist Bernt Rosengren.

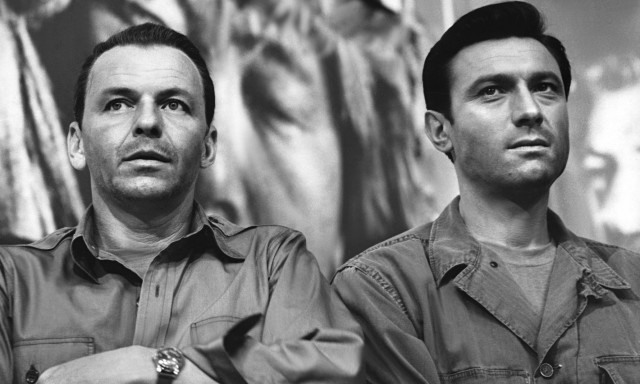

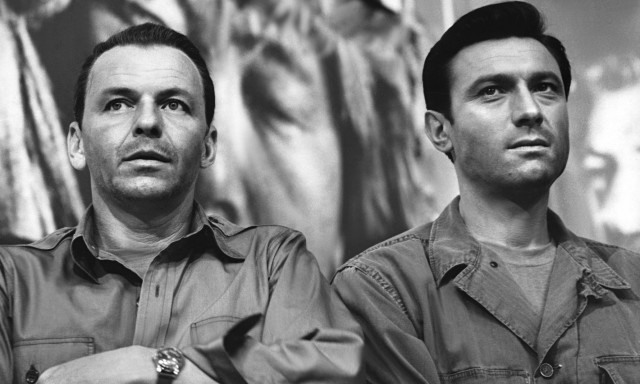

Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra) and Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey) need to clear their heads in The Manchurian Candidate

THE MANCHURIAN CANDIDATE (John Frankenheimer, 1962)

Tuesday, July 26, 5:30, and Wednesday, August 10, 2:35

filmforum.org

John Frankenheimer’s unconventional Cold War conspiracy noir, The Manchurian Candidate, is, quite simply, one of the greatest political thrillers ever made. Ten years after fighting in Korea, Maj. Bennett Marco (Frank Sinatra) remains in the military, working in intelligence. He is haunted by terrifying nightmares in which his unit, led by Sgt. Raymond Shaw (Laurence Harvey), is at a woman’s gardening club lecture that turns into a Communist brainwashing session orchestrated by the menacing Dr. Yen Lo (Khigh Dheigh) of the Pavlov Institute. Meanwhile, the decorated but clearly tortured Shaw has to deal with his power-hungry mother, Mrs. Iselin (Angela Lansbury), who is manipulating everyone she can to ensure that her second husband, the McCarthy-like Sen. John Yerkes Iselin (James Gregory), becomes the Republican vice presidential nominee. As Marco gets to the bottom of the mystery, the clock keeps ticking toward an inevitable crisis with lives on the line and the very future of democracy at stake.

Written by George Axelrod based on the book by Richard Condon (Winter Kills, Prizzi’s Honor), The Manchurian Candidate is a tense, gripping work that feels oddly prescient when seen today. Frankenheimer (Birdman of Alcatraz, Seven Days in May, Seconds) keeps the suspense at Hitchockian levels, particularly as the finale nears, while throwing in doses of dark satire and complex romance. Shaw tries to reconnect with his lost love, Jocelyn Jordan (Leslie Parrish), daughter of erudite Democratic Sen. Thomas Jordan (John McGiver), while Marco is intrigued by Eugenie Rose Cheyney (Janet Leigh); their meeting scene in between cars on a train is an offbeat joy, thought to be impacted by Leigh’s real-life breakup with Tony Curtis that very day. Sinatra, whose previous films included From Here to Eternity and Suddenly — he played a presidential assassin in the latter — once again gets to show off his strong acting chops, especially in a long, uncut scene with Harvey (Room at the Top, Darling) and a fierce fight with Harvey’s servant, Chunjin (Ocean Eleven’s Henry Silva).

Oscar nominee Lansbury relishes her role as Shaw’s villainous mother (in reality, she was only three years older than he was), manipulating her blowhard husband like a puppet. The dramatic music is by composer David Amram (Pull My Daisy), the moody cinematography by Lionel Lindon (All Fall Down, I Want to Live!), with narration by Paul Frees, who went on to voice such cartoon characters as Burgermeister Meisterburger in Santa Claus Is Comin’ to Town and Santa Claus in Frosty the Snowman, in addition to many others. Among the New York City landmarks featured in the film are Central Park and the old Madison Square Garden. And you’ll never look at the Queen of Diamonds or play solitaire quite the same way again. The film’s cultlike status was enhanced because it was out of circulation for a quarter of a century until Sinatra, claiming he hadn’t known that he had owned the the rights since 1972, rereleased it in 1988.

Guido Anselmi (Marcello Mastroianni) is in a bit of a personal and professional crisis in Fellini masterpiece 8½

8½ (Federico Fellini, 1963)

Friday, July 29, 6:00, and Monday, August 1, 8:00

filmforum.org

“Your eminence, I am not happy,” Guido (Marcello Mastroianni) tells the cardinal (Tito Masini) halfway through Federico Fellini’s self-reflexive masterpiece 8½. “Why should you be happy?” the cardinal responds. “That is not your task in life. Who said we were put on this earth to be happy?” Well, film makes people happy, and it’s because of works such as 8½. Fellini’s Oscar-winning eighth-and-a-half movie is a sensational self-examination of film and fame, a hysterically funny, surreal story of a famous Italian auteur who finds his life and career in need of a major overhaul. Mastroianni is magnificent as Guido Anselmi, a man in a personal and professional crisis who has gone to a healing spa for some much-needed relaxation, but he doesn’t get any as he is continually harassed by producers, screenwriters, would-be actresses, and various other oddball hangers-on.

He also has to deal both with his mistress, Carla (Sandra Milo), who is quite a handful, as well as his wife, Luisa (Anouk Aimée), who is losing patience with his lies. Trapped in a strange world of his own creation, Guido has dreams where he flies over claustrophobic traffic and makes out with his dead mother, and his next film involves a spaceship; it doesn’t take a psychiatrist to figure out the many inner demons that are haunting him. Marvelously shot by Gianni Di Venanzo in black-and-white, scored with a vast sense of humor by Nino Rota, and featuring some of the most amazing hats ever seen on film — costume designer Piero Gherardi won an Oscar for all the great dresses and chapeaux — 8½ is an endlessly fascinating and wildly entertaining exploration of the creative process and the bizarre world of filmmaking itself.

Brigitte Bardot shows off both her acting talent and beautiful body in Jean-Luc Godard’s Contempt

CONTEMPT (LE MEPRIS) (Jean-Luc Godard, 1963)

Saturday, July 30, 8:00, and Tuesday, August 9, 8:15

filmforum.org

French auteur Jean-Luc Godard doesn’t hold back any of his contempt for Hollywood cinema in his multilayered masterpiece Contempt. Loosely based on Alberto Moravia’s Il Disprezzo, Contempt stars Michel Piccoli as Paul Javal, a French screenwriter called to Rome’s famed Cinecittà studios by American producer Jeremy Prokosch (Jack Palance ) to perform rewrites on Austrian director Fritz Lang’s (played by Lang himself) adaptation of The Odyssey by ancient Greek writer Homer. Paul brings along his young wife, the beautiful Camille (Brigitte Bardot), whom Prokosch takes an immediate liking to. With so many languages being spoken, Prokosch’s assistant, Francesca Vanini (Giorgia Moll), serves as translator, but getting the various characters to communicate with one another and say precisely what is on their mind grows more and more difficult as the story continues and Camille and Paul’s love starts to crumble. Contempt is a spectacularly made film, bathed in deep red, white, and blue, as Godard and cinematographer Raoul Coutard poke fun at the American way of life. (Both Godard and Coutard appear in the film, the former as Lang’s assistant director, the latter as Lang’s cameraman — as well as the cameraman who aims the lens right at the viewer at the start of the film.)

Bardot is sensational in one of her best roles, whether teasing Paul at a marvelously filmed sequence in their Rome apartment (watch for him opening and stepping through a door without any glass), lying naked on the bed, asking Paul what he thinks of various parts of her body (while Coutard changes the filter from a lurid red to a lush blue), or pouting when it appears that Paul is willing to pimp her out in order to get the writing job. Palance is a hoot as the big-time producer, regularly reading fortune-cookie-like quotes from an extremely little red book he carries around that couldn’t possibly hold so many words. And Lang, who left Germany in the mid-1930s for a career in Hollywood, has a ball playing a version of himself, an experienced veteran willing to put up with Prokosch’s crazy demands. Vastly entertaining from start to finish, Contempt is filled with a slew of inside jokes about the filmmaking industry and even Godard’s personal and professional life, along with some of the French director’s expected assortment of political statements and a string of small flourishes that are easy to miss but add to the immense fun, all set to a gorgeous romantic score by Georges Delerue.

Jean-Luc Godard’s Band of Outsiders is a different kind of heist movie

BANDE À PART (BAND OF OUTSIDERS) (Jean-Luc Godard, 1964)

Tuesday, August 2, 8:10, Wednesday, August 3, 12:30, and Tuesday, August 9, 6:10

filmforum.org

When a pair of disaffected Parisians, Arthur (Claude Brasseur) and Franz (Sami Frey), meet an adorable young woman, Odile (Anna Karina), in English class, they decide to team up and steal a ton of money from a man living in Odile’s aunt’s house. As they meander through the streets of cinematographer Raoul Coutard’s black-and-white Paris, they talk about English and wealth, dance in a cafe while director Jean-Luc Godard breaks in with voice-over narration about their character, run through the Louvre in record time, and pause for a near-moment of pure silence. Godard throws in plenty of commentary on politics, the cinema, and the bourgeoisie in the midst of some genuinely funny scenes. One of Godard’s most accessible films, Band of Outsiders is no ordinary heist movie; based on Dolores Hitchens’s novel Fool’s Gold, it is the story of three offbeat individuals who just happen to decide to attempt a robbery while living their strange existence, as if they were outside from the rest of the world. The trio of ne’er-do-wells might remind Jim Jarmusch fans of the main threesome from Stranger Than Paradise (1984), except Godard’s characters are more aggressively persistent.

Tom Courtenay and Julie Christie get close in John Schlesinger’s Billy Liar

BILLY LIAR (John Schlesinger, 1963)

Wednesday, August 3, 2:40 & 6:00

filmforum.org

Based on the novel by Keith Waterhouse (which he also adapted into a play with Willis Hall and which later became a musical), John Schlesinger’s Billy Liar is a prime example of the British New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s, which features work by such directors as Lindsay Anderson, Joseph Losey, Ken Russell, Nicolas Roeg, and Karel Reisz. Tom Courtenay stars as William Fisher, a ne’er-do-well ladies’ man who drudges away in a funeral home and dates (and lies to) multiple women, all the while daydreaming of being the president of the fictional country of Ambrosia. Billy lives in his own fantasy world where he can suddenly fire machine guns at people who bother him and be cheered by adoring crowds as he leads a marching band. Reminiscent of the 1947 American comedy The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, in which Danny Kaye dreams of other lives to lift him out of the doldrums, Billy Liar is also rooted in the reality of post-WWII England, represented by Billy’s father (Wilfred Pickles), who thinks his son is a no-good lazy bum. Shot in black-and-white by Denys Coop (This Sporting Life, Bunny Lake Is Missing), the film glows every time Julie Christie appears playing Liz, a modern woman who takes a rather fond liking to Billy. The film made Christie a star; Schlesinger next cast her in Darling, for which she won the Oscar for Best Actress.

The Beatles’ A Hard Day’s Night gets back to Film Forum for 1962-63-64 series

A HARD DAY’S NIGHT (Richard Lester, 1964)

Friday, August 5, 2:35 & 9:25, Saturday, August 6, 12:30 & 4:35

filmforum.org

The Beatles recently invaded America again with Peter Jackson’s three-part documentary Get Back, about the making of Let It Be. The Film Forum series takes us back to their debut movie, the deliriously funny anarchic comedy A Hard Day’s Night. Initially released on July 6, 1964, in the UK, AHDN turned out to be much more than just a promotional piece advertising the Fab Four and their music. Instead, it quickly became a huge critical and popular success, a highly influential work that presaged Monty Python and MTV while also honoring the Marx Brothers, Buster Keaton, Jacques Tati, and the French New Wave. Directed by Richard Lester, who had previously made the eleven-minute The Running Jumping & Standing Still Film with Peter Sellers and would go on to make A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Petulia, and The Three Musketeers, the madcap romp opens with the first chord of the title track as John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr are running down a narrow street, being chased by rabid fans, but they’re coming toward the camera, welcoming viewers into their crazy world. (George’s fall was unscripted but left in the scene.) As the song blasts over the soundtrack, Lester introduces the major characters: the four moptops, who are clearly having a ball, led by John’s infectious smile, in addition to Paul’s “very clean” grandfather (Wilfrid Brambell, who played a dirty old man in the British series Steptoe and Son, the inspiration for Sanford and Son) and the band’s much-put-upon manager, Norm (Norman Rossington). Lester and cinematographer Gilbert Taylor (Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb, Repulsion, Star Wars) also establish the pace and look of the film, a frantic black-and-white frolic shot in a cinema-vérité style that is like a mockumentary taking off from where François Truffaut’s 400 Blows ends.

The boys eventually make it onto a train, which is taking them back to their hometown of Liverpool, where they are scheduled to appear on a television show helmed by a hapless director (Victor Spinetti, who would star in Help as well) who essentially represents all those people who are dubious about the Beatles and the sea change going on in the music industry. Norm and road manager Shake (John Junkin) have the virtually impossible task of ensuring that John, Paul, George, and Ringo make it to the show on time, but there is no containing the energetic enthusiasm and contagious curiosity the quartet has for experiencing everything their success has to offer — while also sticking their tongues out at class structure, societal trends, and the culture of celebrity itself. Lester and Oscar-nominated screenwriter Alun Owen develop each individual Beatle’s unique character through press interviews, solo sojourns (the underappreciated Ringo goes off on a kind of vision quest; George is mistaken by a fashion fop for a model), and an endless stream of spoken and visual one-liners. (John sniffs a Coke bottle; a reporter asks George, “What do you call your hairstyle?” to which the Quiet One replies, “Arthur.”) Oh, the music is rather good too, featuring such songs as “I Should Have Known Better,” “All My Loving,” “If I Fell,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “I’m Happy Just to Dance with You,” “This Boy,” and “She Loves You.” The working name for the film was Beatlemania, but it was eventually changed to A Hard Day’s Night, based on a Ringo malapropism, forcing John and Paul to quickly write the title track. No mere exploitation flick, A Hard Day’s Night is one of the funniest, most influential films ever made, capturing a critical moment in pop-culture history and unleashing four extraordinary gentlemen on an unsuspecting world. Don’t you dare miss this glorious eighty-five-minute explosion of sheer, unadulterated joy.