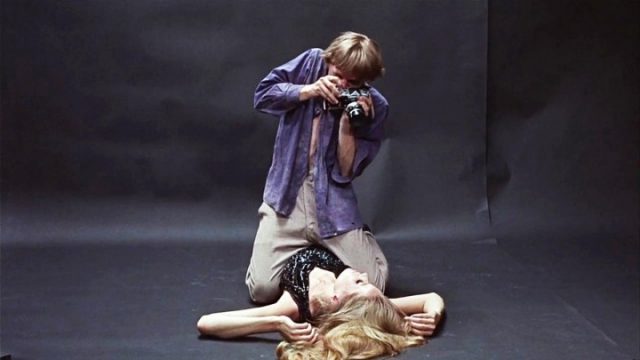

Thomas (David Hemmings) focuses on Veruschka in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up

BLOW-UP (BLOWUP) (Michelangelo Antonioni, 1966)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

July 28 – August 3

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni calls into question everything we see and hear, in photographs, on film, and in real life, in his 1966 counterculture masterpiece, Blow-Up, which is being shown July 28 to August 3 in a new DCP restoration at Film Forum. Antonioni’s first English-language film — part of a three-picture deal with producer Carlo Ponti that would also include the disappointing Zabriskie Point and the quirky existential suspense thriller The Passenger — lets viewers know from the very start that their eyes and ears are going to be tested as the letters of the opening credits frame indecipherable action, frustrating the viewer’s desire to understand what is going on. David Hemmings stars as Thomas, a successful fashion photographer in 1960s Swinging London who is tired of the phoniness and artifice inherent in his profession and instead has ambitions to become a black-and-white documentary photographer, as he and his agent, Ron (Peter Bowles), put together a book focusing on the many ills of society. Of course, he does so while riding around in a Rolls-Royce convertible and in between shooting such models as Veruschka (von Lehndorff), whom he practically makes love to during their session but doesn’t give a hoot about once he puts down the camera. He also gets fed up easily with a quartet of fabulously dressed models (the makeup and clothes come courtesy of costume designer Jocelyn Rickards), telling them to shut their eyes as he leaves, controlling what they see and don’t see, much like a film director. Thomas eventually heads out to lush, green Maryon Park, where he takes pictures of two people, a younger woman (Vanessa Redgrave) cavorting with an older man (Ronan O’Casey), apparently in the midst of a secret tryst. The woman, Jane, rushes over to Thomas and demands he give her the film; he invites her to his studio, where she is willing to do just about anything to get back the negatives. Wondering what was so incriminating about the photographs, Thomas soon makes blow-up after blow-up, examining them closely and ultimately believing that he has captured a murder on film. He also finds out that getting to the truth isn’t going to be easy, especially when he keeps allowing himself to become distracted by his wild lifestyle.

Italian auteur Michelangelo Antonioni calls into question everything we see and hear, in photographs, on film, and in real life, in his 1966 counterculture masterpiece, Blow-Up, which is being shown July 28 to August 3 in a new DCP restoration at Film Forum. Antonioni’s first English-language film — part of a three-picture deal with producer Carlo Ponti that would also include the disappointing Zabriskie Point and the quirky existential suspense thriller The Passenger — lets viewers know from the very start that their eyes and ears are going to be tested as the letters of the opening credits frame indecipherable action, frustrating the viewer’s desire to understand what is going on. David Hemmings stars as Thomas, a successful fashion photographer in 1960s Swinging London who is tired of the phoniness and artifice inherent in his profession and instead has ambitions to become a black-and-white documentary photographer, as he and his agent, Ron (Peter Bowles), put together a book focusing on the many ills of society. Of course, he does so while riding around in a Rolls-Royce convertible and in between shooting such models as Veruschka (von Lehndorff), whom he practically makes love to during their session but doesn’t give a hoot about once he puts down the camera. He also gets fed up easily with a quartet of fabulously dressed models (the makeup and clothes come courtesy of costume designer Jocelyn Rickards), telling them to shut their eyes as he leaves, controlling what they see and don’t see, much like a film director. Thomas eventually heads out to lush, green Maryon Park, where he takes pictures of two people, a younger woman (Vanessa Redgrave) cavorting with an older man (Ronan O’Casey), apparently in the midst of a secret tryst. The woman, Jane, rushes over to Thomas and demands he give her the film; he invites her to his studio, where she is willing to do just about anything to get back the negatives. Wondering what was so incriminating about the photographs, Thomas soon makes blow-up after blow-up, examining them closely and ultimately believing that he has captured a murder on film. He also finds out that getting to the truth isn’t going to be easy, especially when he keeps allowing himself to become distracted by his wild lifestyle.

Jane (Vanessa Redgrave) is worried about photos Thomas (David Hemmings) took in Blow-Up

Blow-Up, which was parodied in Mel Brooks’s High Anxiety, reimagined by Brian De Palma as Blow Out, and a direct influence on Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation, was inspired by Julio Cortázar’s short story about a translator, “Las babas del diablo” (“The Devil’s Drool”), and written by Antonioni and regular collaborator Tonino Guerra (L’avventura, L’eclisse, The Red Desert), with English-language dialogue by poet and playwright Edward Bond. Antonioni dances all over the line between fiction and reality: Thomas’s studio belongs to photographer Jon Cowan; many of Thomas’s pictures were taken by photojournalist Don McCullin; Thomas himself is based on London photographer David Bailey; the abstract paintings by Thomas’s neighbor, Bill (John Castle), are by Ian Stephenson; the band in the club scene is the Yardbirds; and the tennis-playing mimes are husband and wife real mimes Claude and Julian Chagrin. Herbie Hancock’s groovy score is primarily heard when Thomas turns on a radio or puts on a record, ambient sound instead of soundtrack music coming from nowhere. Meanwhile, Antonioni challenges the viewer again and again to think twice about what they see and hear. At one point Antonioni follows Thomas’s gaze up into the trees, but when the camera returns to Thomas, he is looking elsewhere. While Thomas is studying the photos he took in the park, trying to uncover what happened as if editing a film, the wind from the park can impossibly be heard. Thomas is often peering through blinds, not sure of what he is seeing. A pair of wannabe models (Jane Birkin and Gillian Hills) tear apart Thomas’s fake photographic background as if breaking the boundaries between the real and the fabricated. When Thomas shows one of the park photographs to Bill’s girlfriend, Patricia (Sarah Miles), she says, “It looks like one of Bill’s paintings.”

And when Yardbirds guitarist Jeff Beck gets frustrated with one of the speakers behind him, he destroys his guitar as bandmates Jimmy Page and singer Keith Relf continue playing “Stroll On” as if nothing is happening. Meanwhile, the crowd stands still like a bunch of zombies, refusing to stroll on or move at all, until Beck throws the broken neck of his guitar, now an object that can no longer emit sounds, into the audience, where it’s up to others to determine its value. The stagnation also relates to a huge propeller Thomas buys from an antiques store, as if he’s desperate to propel his life forward. Does Antonioni really get that literal? It’s hard to tell, but nearly every shot is ripe for interpretation, every directorial decision a careful choice imbued with meaning. When Thomas drives through an antiwar march, two protesters put a sign saying “Go away!” in his backseat, where the propeller will be put later. Blow-Up concludes with one of the most creative finales in the history of cinema. The troupe of mimes seen earlier returns, playing tennis in the park, but without a ball. Just follow the gazes of the mimes and Thomas, and listen closely as well, then watch what he does with his camera. It ingeniously encapsulates everything that has come before, but without a single word being spoken. It’s an absolutely bravura ending to an absolutely bravura film.