POOL PARTY

Metrograph

7 Ludlow St. between Canal & Hester Sts.

August 5-14

212-660-0312

metrograph.com

www.focusfeatures.com

With New York City sweltering in a muggy, sweat-drenching summer with temps that have stayed in the nineties, Metrograph offers two things to cool you off that usually don’t go together: air-conditioning and swimming. But that’s just what their new series, “Pool Party,” does, consisting of seven films in which characters go for a dip, for good and for bad.

The series kicks off with François Ozon’s beguiling mystery Swimming Pool, in which Charlotte Rampling shows Ludivine Sagnier that she still has it, followed by Jacques Deray’s 1969 erotic thriller La Piscine, in which Jane Birkin shakes things up between Alain Delon and Romy Schneider. Burt Lancaster swims home through suburban backyard pools in Frank Perry’s 1968 adaptation of John Cheever’s 1964 short story “The Swimmer.” Selena Gomez and friends take a wild road trip in Harmony Korine’s 2012 Spring Breakers, meeting up with a metallic-smiling James Franco. Elsie Fisher finds more trouble than she bargained for as a middle school vlogger in Bo Burnham’s bittersweet debut, Eighth Grade. British artist David Hockney makes a big splash in Jack Hazan’s 1974 hybrid docudrama, A Bigger Splash. And Lucretia Martel traces the fall of a bourgeois family in her 2001 debut, La Ciénaga. Below is a deeper dive into two of the films; get those bathing suits on and jump in to beat the heat!

SWIMMING POOL (François Ozon, 2003)

Friday, August 5, 2:45

Sunday, August 7, 12:20

metrograph.com

www.focusfeatures.com

Charlotte Rampling is divine in Swimming Pool, François Ozon’s playfully creepy mystery about a popular British crime novelist taking a break from the big city (London) to recapture her muse at her publisher’s French villa, only to be interrupted by the publisher’s hot-to-trot teenage daughter. Rampling stars as Sarah Morton, a fiftysomething novelist who is jealous of the attention being poured on young writer Terry Long (Sebastian Harcombe) by her longtime publisher, John Bosload (Game of Thrones’s Charles Dance). John sends Sarah off to his elegant country house, where she sets out to complete her next Inspector Dorwell novel in peace and quiet. But the prim and proper — and rather bitter and cynical — Sarah quickly has her working vacation intruded upon by Julie (Ludivine Sagnier), John’s teenage daughter, who likes walking around topless and living life to the fullest, clearly enjoying how Sarah looks at her and judges her. “You’re just a frustrated English writer who writes about dirty things but never does them,” Julie says, and soon Sarah is reevaluating the choices she’s made in her own life. Rampling, who mixes sexuality with a heart-wrenching vulnerability like no other actress (see The Night Porter, The Verdict, and Heading South), more than holds her own as the primpy old maid in the shadow of a young beauty, even tossing in some of nudity to show that she still has it. (Rampling also posed nude in her sixties in a series of photographs by Juergen Teller alongside twentysomething model Raquel Zimmerman, so such “competition” is nothing to her.)

Julie (Ludivine Sagnier) and Sarah (Charlotte Rampling) come to a kind of understanding in François Ozon’s Swimming Pool

Rampling has really found her groove working with Ozon, having appeared in five of his films, highlighted by a devastating performance in Under the Sand as a wife dealing with the sudden disappearance of her husband. Sagnier, who has also starred in Ozon’s Water Drops on Burning Rocks and 8 Women, is a delight to watch, especially as things turn dark. Swimming Pool is very much about duality; the film opens with a shot of the shimmering Thames river while the title comes onscreen and Philippe Rombi’s score of mystery and danger plays, and later Sarah says, “I absolutely loathe swimming pools,” to which Julie responds, “Pools are boring; there’s no excitement, no feeling of infinity. It’s just a big bathtub.” (“It’s more like a cesspool of living bacteria,” Sarah adds.) Ozon (Time to Leave, Criminal Lovers) explores most of the seven deadly sins as Sarah and Julie get to know each other all too well.

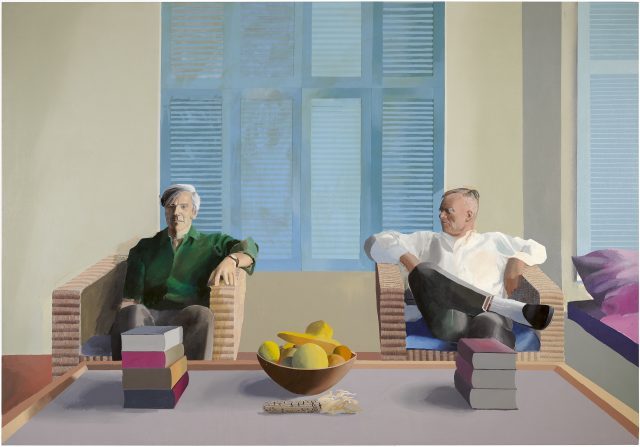

David Hockney works on his masterpiece in Jack Hazan’s A Bigger Splash

A BIGGER SPLASH (Jack Hazan, 1974)

Saturday, August 6, 2:30

Sunday, August 7, 5:00

Saturday, August 13, 7:15

metrograph.com

Coinciding with Pride celebrations throughout New York City in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots in June 2019, Metrograph premiered a 4K restoration of Jack Hazan’s pivotal 1974 A Bigger Splash, a fiction-nonfiction hybrid that was a breakthrough work for its depiction of gay culture as well as its inside look at the fashionable and chic Los Angeles art scene of the early 1970s. In November 2018, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) sold at auction for $90.3 million, the most ever paid for a work by a living artist. A Bigger Splash, named after another of Hockney’s paintings — both are part of a series of canvases set around pools in ritzy Los Angeles — takes place over three years, as the British artist, based in California at the time, hangs out with friends, checks out a fashion show, prepares for a gallery exhibition, and works on Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) in the wake of a painful breakup with his boyfriend, model, and muse, Peter Schlesinger, who is a key figure in the painting.

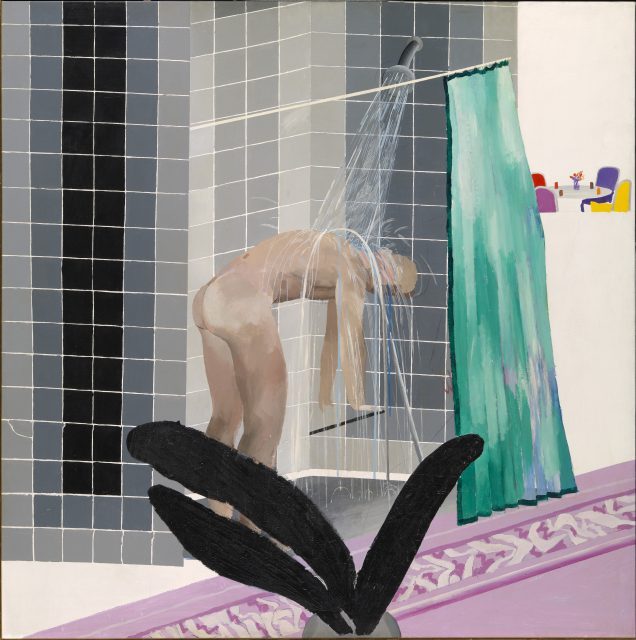

It’s often hard to know which scenes are pure documentary and which are staged for the camera as Hazan and his then-parter, David Mingay, who served as director of photography, tag along with Hockney, who rides around in his small, dirty BMW, meeting up with textile designer Celia Birtwell, fashion designer Ossie Clark, curator Henry Geldzahler, gallerist John Kasmin, artist Patrick Procktor, and others, who are identified only at the beginning, in black-and-white sketches during the opening credits. The film features copious amounts of male nudity, including a long sex scene between two men, a group of beautiful boys diving into a pool in a fantasy sequence, and Hockney disrobing and taking a shower. Hockney’s assistant, Mo McDermott, contributes occasional voice-overs; he also poses as the man standing on the deck in Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), only to be replaced by Schlesinger later. There are several surreal moments involving Hockney’s work: He cuts up one painting; Geldzahler gazes long and hard at himself in the double portrait of him and Christopher Scott; and Hockney tries to light the cigarette Procktor is holding in a painting as Procktor watches, cigarette in hand, mimicking his pose on canvas. At one point Hockney is photographing Schlesinger in Kensington Gardens, reminiscent of Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow-Up, which questions the very nature of capturing reality on film.

Hockney was so upset when he first saw A Bigger Splash, which Hazan made for about twenty thousand dollars, that he offered to buy it back from Hazan in order to destroy it; Hazan refused, and Hockney went into a deep depression. His friends ultimately convinced him that it was a worthwhile movie and he eventually accepted it. It’s a one-of-a-kind film, a wild journey that goes far beyond the creative process as an artist makes his masterpiece. Hockney, who turned eighty-five last month, has been on quite a roll of late. He was the subject of a 2016 documentary by Randall Wright, was widely hailed for his 2018 Met retrospective, and had a major drawing show at the Morgan Library in 2020-21. In addition, Catherine Cusset’s novel, Life of David Hockney, was published in English in 2019, a fictionalized tale that conceptually recalls A Bigger Splash.

Just in time to coincide with Pride celebrations throughout New York City in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, Metrograph is premiering a 4K restoration of Jack Hazan’s pivotal 1974 A Bigger Splash, a fiction-nonfiction hybrid that was a breakthrough work for its depiction of gay culture as well as its inside look at the fashionable and chic Los Angeles art scene of the early 1970s. This past November, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) sold at auction for $90.3 million, the most ever paid for a work by a living artist. A Bigger Splash, named after another of Hockney’s paintings — both are part of a series of canvases set around pools in ritzy Los Angeles — takes place over three years, as the British artist, based in California at the time, hangs out with friends, checks out a fashion show, prepares for a gallery exhibition, and works on Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) in the wake of a painful breakup with his boyfriend, model, and muse, Peter Schlesinger, who is a key figure in the painting.

Just in time to coincide with Pride celebrations throughout New York City in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of the Stonewall riots, Metrograph is premiering a 4K restoration of Jack Hazan’s pivotal 1974 A Bigger Splash, a fiction-nonfiction hybrid that was a breakthrough work for its depiction of gay culture as well as its inside look at the fashionable and chic Los Angeles art scene of the early 1970s. This past November, David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) sold at auction for $90.3 million, the most ever paid for a work by a living artist. A Bigger Splash, named after another of Hockney’s paintings — both are part of a series of canvases set around pools in ritzy Los Angeles — takes place over three years, as the British artist, based in California at the time, hangs out with friends, checks out a fashion show, prepares for a gallery exhibition, and works on Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) in the wake of a painful breakup with his boyfriend, model, and muse, Peter Schlesinger, who is a key figure in the painting.