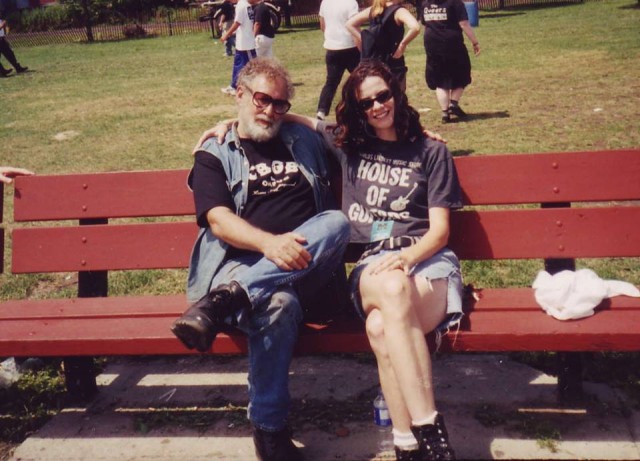

Nick and Jake collaborate both personally and professionally, using their life together as a starting point in their art

HERE

145 Sixth Ave. at Dominick St.

April 23 – May 4 (Tuesday – Sunday, 8:30), $10 in advance, $20 within twenty-four hours

Installation free Tuesday – Sunday 2:00 – 10:00

212-647-0202

www.here.org

www.nickandjakestudio.com

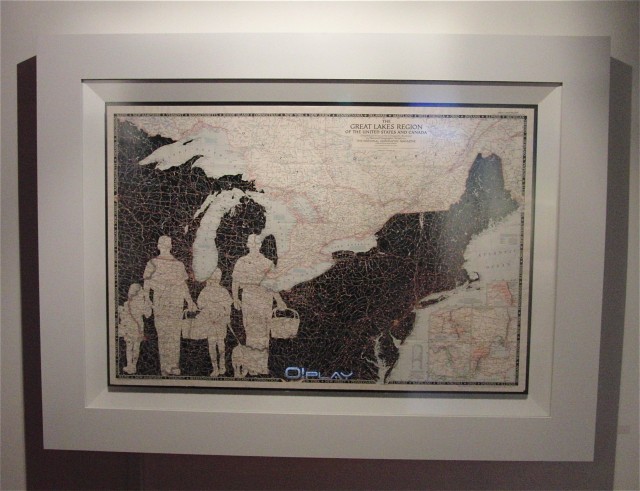

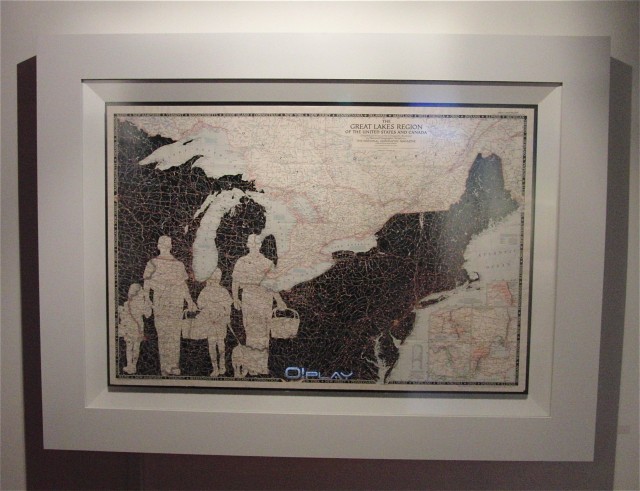

Married couple and professional partners Nick Vaughan and Jake Margolin have taken over HERE, filling the downtown arts center with the multimedia immersive presentation A Marriage: 1 (Suburbia). Employing the visual sensibility of Gilbert & George, Nick and Jake examine what has become of the American Dream and the concept of the nuclear family through photography, video, performance, and installation that will continue to evolve from April 23 through May 4. In the art exhibit, which is free, they employ maps that have been reconfigured to portray superimposed families on them and/or video of the two men in the background; pages from John Updike’s Rabbit Run torn out and put on a wall, with highlighted phrases and blue lines connecting them to tell a different kind of suburban story; a hallway of colorful light boxes depicting the conventional 1950s ideal of the American family; and wall sketches that will be added to over the course of the two weeks. Every night will feature a sixty-minute live show ($10 in advance, $20 within twenty-four hours) featuring text written by Jessica Almasy and performed by Jess Barbagallo, with long-duration actions by Brandon Hutchinson and Libby King (April 23-25), Sean Donovan (April 26-30), and Chantal Pavageaux (May 1-4); brand-new Guggenheim Fellow and award-winning choreographer Faye Driscoll serves as consulting director.

“It was super fun for me to work with Nick and Jake; they are both so earnest, humble, and smart and amazingly open inside their process,” says Driscoll. “I loved working on ideas around performance in a visual art context; it opened up my thinking around my own work and gave me some new structures of making, and permission for a different type of exploration. But I think it really helped that all three of us have backgrounds in working in theater. We very easily found a common language around dramaturgical questions and rigor. And we all have an easy willingness to engage in the labor involved in making things. We did a lot of figuring out on our feet, which is how I think best. I think in A Marriage there is clear play with that merged and excessive space of togetherness of coupledom, but as opposed to the work just becoming insular and exclusive, there is actually something deeply generous and activist happening in what Nick and Jake are creating.” At the center of that togetherness and activism is an exploration of America’s changing relationship with same-sex marriage. Nick and Jake, who are still part of the TEAM arts collective where they met, discussed that and more as they prepared for the start of this fascinating undertaking.

twi-ny: Did either of you grow up in the suburbs?

Jake: Neither of us grew up in the suburbs. We both grew up in small university cities, Nick in Fort Collins, Colorado, and I in Berkeley, California. I think it’s safe to say that we both grew up with a healthy distrust of the suburbs — growing up, my family hosted a singing group at our house in which Malvina Reynolds’s “Little Boxes” was a pretty frequent request. Growing up with parents who had no interest in the suburban version of the American Dream is part of why I grew up thinking that the suburbs were for other people. But I also felt that because I was gay it wasn’t an option, even if I wanted it. I grew up knowing a fair number of kids who lived in the suburbs of the Bay Area, and many of them were nonwhite, and not wealthy, which I mention only to say that I didn’t have a view of the suburbs as a place that was exclusively white or monied. But my sense of it was that the suburbs were exclusively heterosexual. And as I realized that I didn’t fit into that, I had a real sense that even had I wanted anything to do with the suburbs, I wouldn’t be welcome — that the ’burbs weren’t for people like me.

twi-ny: What do you think has happened to that American Dream since your were kids?

Jake: When we talk about the “American Dream” we are talking about the heteronormative version that aspires to a suburban nuclear family. There are as many different versions of the American Dream as there are people in this country, so I just want to clarify that we are using it as a cliché. And I think a major shift has happened since we were kids, which is that this version of the American Dream is now opened up to include LGBTQ people. Even growing up in a hyperliberal place, I had a sense of gay people as being abnormal – a deviance from the norm that are tolerated because Berkeleyites are tolerant and open-minded people, but still a group of people who are in some way going to have to live on the outside of mainstream society. As many things about gay culture have been accepted into the mainstream since we were kids, now that set of aspirations that were traditionally exclusively for heterosexuals, aspirations towards suburbia, the nuclear family, and all of that – are on the table.

Nick and Jake explore the suburban ideal of the American Dream in immersive multimedia installation (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

twi-ny: An earlier part of A Marriage at HERE included your watching twenty hours of Fox News. What are your feelings toward America’s evolving relationship with same-sex marriage, primarily as portrayed in the media?

Jake: That piece was trying to get at how we are surrounded by these media portrayals of same-sex marriage, almost swimming in these sound bites. And we’d been floored by the general tone on Fox News about same-sex marriage – it felt so belittling whenever we saw it. That said, I should fess up that Nick and I don’t own a TV, and other than when we are on tour with the TEAM or other projects (or holing up in motels to make art pieces), we watch very little TV. Probably my greatest exposure to how the media portrays same-sex marriage is the package of clippings from the New York Times and various Bay Area publications on the topic that my mother sends us every few months.

In general I am so thrilled by the growing acceptance of same-sex marriage, both by the country in general and by the media that I am exposed to. Thrilled and grateful for the hard work and sacrifices that have been made by so many people to make this happen. However, I feel a certain ambivalence about this acceptance because I wonder who’s terms this acceptance is on. I wonder about the sense that we are accepted as long as we conform to a version of heteronormative social structures that people have spent the last however long – forty years? – trying to dismantle. I grew up with plenty of models of people living outside the construct of marriage – whether it be raising a family with their partner and never getting married or remaining single. So while Nick and I have a pretty traditional marriage in all respects other than our gender, I don’t have a sense that it is an inherently superior situation than any other. It just works for us.

As we were creating this piece, this ambivalence felt very strong – a real sense of “Now we have the option of fitting into all this iconography, but do we want to have anything to do with it? This inevitable-feeling march towards the mainstream, do we want it or are we losing something really important tied to our heritage as a people relegated to being the Other.” And then the Prop 8 case gets argued in front of the Supreme Court, and when I hear the justices waffling about “Is this really the right time?” and “Can’t we just wait for the states to decide on their own?” I find that I swing completely in the opposite direction and feel strongly, “How dare anyone say that I am different or that our relationship is in any way inferior” and find that I want that mainstream acceptance – that I feel completely entitled to it.

twi-ny: Among your collaborators is one of our favorite people, Faye Driscoll. How did that collaboration come about?

Nick: She’s one of our favorite people too! I first met Faye when I designed the set for Taylor Mac’s The Lily’s Revenge a few years ago. For the third section of the epic piece (which Faye choreographed) we stripped the space bare and taped out “‘scenery’ on the wall.” I’ve been following her work ever since and have collaborated on a couple of operas which she choreographed and I designed.

It was after the premiere of You’re Me at the Kitchen, though, that Jake and I decided to ask her to help us out with this project. She has such a clear and deceptively simple way of cutting to the core of visual ideas. You always have the sense watching her work that things are actually happening, that there’s a real exchange taking place. She’s also one of the smartest people I know. It seemed, therefore, only natural to ask her to help us curate and develop the eleven nightly actions for our piece, none of which is dance, per-se. . . .

twi-ny: The images of you and Jake in the installation evoke the work of Gilbert and George. Did they serve as any kind of influence or inspiration?

Nick: Absolutely. I don’t know if it would have been possible for the two of us as a couple and artistic team not to address Gilbert and George in some way. At some level I think their work was probably influencing us from the very beginning of our collaborations, but I don’t know that we realized it until their retrospective at the Brooklyn Museum a few years ago.

I think there is a very different approach to performance and it’s something that has certainly come up multiple times as we’ve developed the nightly actions. G&G were revolutionary in that they presented themselves as objects, stripped (or at least muted) of identity. Our presence in our work (hopefully) serves to frame the world through our eyes so you’re looking with us, not at us.

But there are small references peppered throughout the piece: There’s a large wax panel work that bears a slight reference to G&G in its framing. There are three sprayed-paint performances that I think in some way give a little nod to the silver and red body paint of the duo. But there are also other little nods to other artists who have inspired us.

There’s a piece in the downstairs hallway (and bathrooms) that lightly reference this wonderful Sol Lewitt piece Jake and I saw at MassMOCA last year in which he took an art criticism journal and diligently connected every use of the word “art” so you got this strange kind of matrix and it turned the text into this impenetrable geometric construction. We’ve taken a much looser approach, deconstructing John Updike’s Rabbit Run and attempting to give some kind of graphic anchor to the images that feel related, from a very subjective set of criteria.

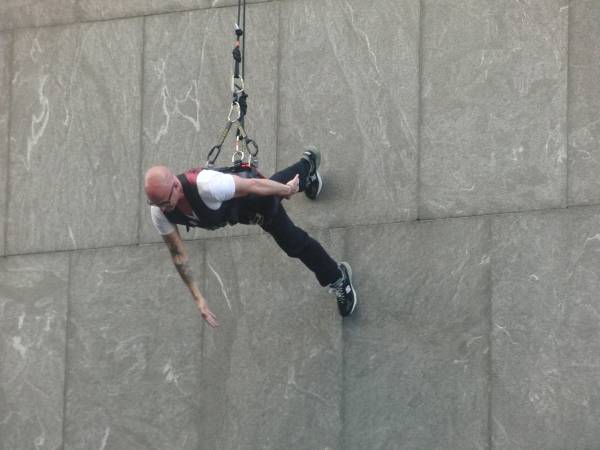

Installation includes geographic portraits made of cut maps emphasizing negative space (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

twi-ny: You met while working together at the Team, and now you’re married. How has the dynamic of living, working, and performing together impacted your relationship?

Jake: One thing we joke about is that normally your spouse is the person you can come home to and gripe about work and your coworkers. . . . We can’t really do that. Our collaboration came out of conversations that we had while on tour with the TEAM as well as while on tour with Yoshiko Chuma. It feels that through the TEAM we have the most wonderful outlet for making theater with a group of the smartest and most talented people we know. And we realized that we shared an interest in installation art and how performance functions in that setting, and what started as daydreaming while on tour turned into works-in-progress at various places and ultimately this residency at HERE.

The show will change over time, with people encouraged to return to see where things have gone. Dare we read anything into the work as coming from your real-life marriage?

Jake: Each night of the show we will do a different performance action, so they will accumulate over the course of the run, while a fourteen-day-long action in which we, Brandon Hutchinson, Libby King, Sean Donovan, and Chantal Pavageaux read the entire oral arguments of Perry v. Schwarzenegger into clear bags, creating an expanding sculpture of the captured breath. We hope that people will come by later in the run to see how this has evolved, and the tickets are structured to encourage that – the ticket that you purchase is good for return visits so that people might stop by for ten minutes on a later night to check in on it all.

This question makes me laugh – I suppose it does feel like our marriage evolves over time and that if you check back in with us at a later point it will have gotten larger and more complicated and more fleshed out . . . but I suspect that is true of all relationships.

Earlier this year we were debating whether we should condense the performance actions into brief excerpts that could all be performed each night — and ultimately decided that they really only function if they are given the room to take a whole evening each — that their duration is at the core of the thing. Perhaps there’s an analogy there with our marriage, and probably with marriage in general – that it’s slow work, and things take time to breathe and grow, and that in fact this expansive time is a really good thing. A great perk of being married is that there isn’t the pressure to get things right immediately, because we’re in it for the long haul.

(A Marriage: 1 (Suburbia) runs April 23 – May 4 at HERE and will include several special programs. The April 24 performance will be preceded by “Cocktails & Context” at 7:30 and will be followed by the panel discussion “The Ambiguity of Acceptance,” and the May 1 show will be followed by a discussion moderated by Risa Shoup and featuring Steven Cheslik-DeMeyer, Erin Markey, Glenn Marla, and Tony Osso.)