A dodo and a young boy are best friends fighting to survive in Dead as a Dodo (photo by Richard Termine)

DEAD AS A DODO

Baruch PAC

55 Lexington Ave. between Twenty-Fourth & Twenty-Fifth Sts.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 9, $55

utrfest.org

bpac.baruch.cuny.edu

“The race is over!” the Dodo suddenly calls out in Lewis Carroll’s 1865 masterpiece, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Its animal friends crowd around, pant, and ask, “But who has won?”

You might be surprised by who wins in Wakka Wakka’s Dead as a Dodo, an awe-inspiring, visually stunning parable about the potential end of the human race and the tenuous future of the planet, sensationally staged with puppets. Running through February 9 at Baruch PAC as part of the Under the Radar festival, the eighty-minute extravaganza plays off the old adage “as dead as a dodo,” which refers to a person, place, or thing that is either no longer alive or decidedly out of date. The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) itself was a flightless bird of Mauritius that was last spotted in 1662.

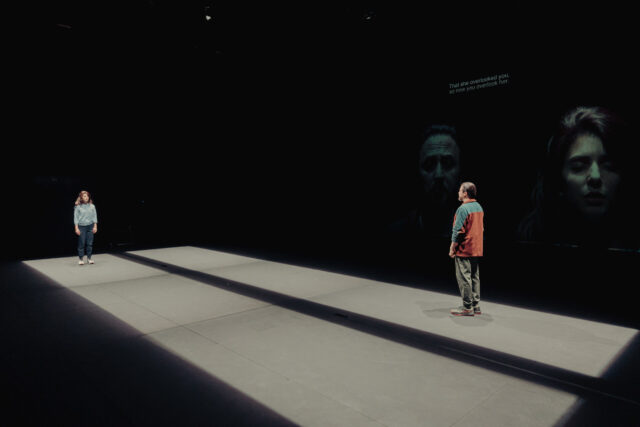

In the Bone Realm, a pair of skeletons, a female dodo and a young boy, are besties. The boy is searching for bones to replace his arm and leg, digging into the basalt for anything that will fit. “So I’m missing an arm / And my ribs are all broken / I’ve lost half my teeth / And my skull is cracked open,” he sings. “Yes, I’m falling apart / And I’m close to the end / Still I’ve gotta take heart / Because I’ve got a friend / And my friend is a dodo.”

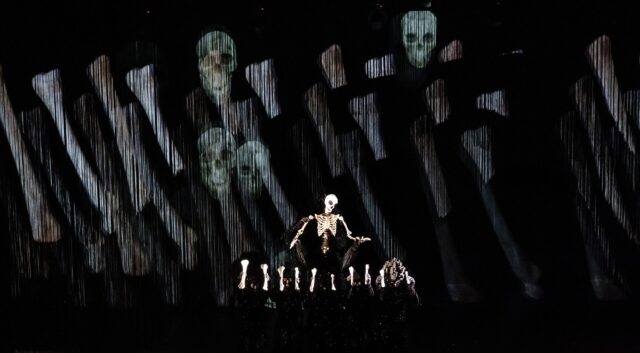

The two are always on the lookout for the Bone King and his daughter, the conniving princess, who are determined to own every bone in the land and are prepared to rip them right off the boy if necessary. “After life is stripped away / All the flesh has decayed / What remains? / Nothing but the bones / Nothing but the bones,” the king chants with dastardly glee. “All the bones in the fields are mine / You can try to take ’em if you got the spine.”

The greedy Bone King wants to own it all in sensationally eerie Dead as a Dodo (photo by Erato Tzavara)

As the boy fears he is disappearing, he notices that the dodo has grown a new feather or two — indications of life. When the Bone King discovers the feathers as well, the Bone Doctor, a kind of Grim Reaper, commands, “It is a plague upon our kingdom. There is only one thing to do. . . . You, sire! — Must chop it up and throw it into the fiery waters of the River Styx!”

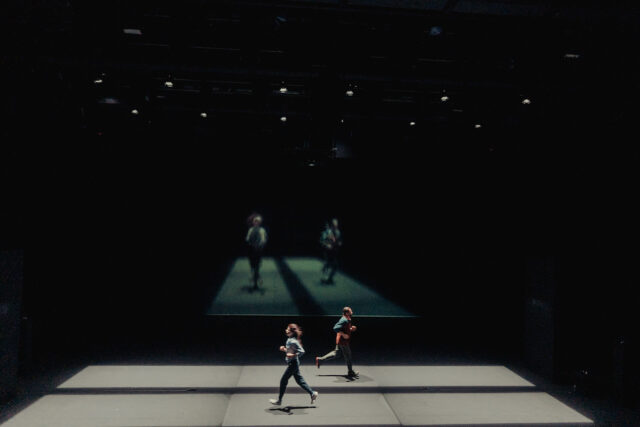

The boy and the dodo then set off on a dangerous journey into other realms, where they meet a scavenging demon, a chatty gondolieri, a giant glowing fish, devil goats, a woolly mammoth, and a scientist named Phinneas who believes that the resurgent dodo is a sign that “the Age of Shimmering Darkness and Fog is coming to an end.”

But no one knows what will happen if the dodo actually returns to the Living Realm, rising like a phoenix. “Ha! That is not the order of things,” the gondolieri argues. “The river only flows in one direction.”

The staging of Dead as a Dodo is a marvel of technology and DIY ingenuity. There are three layers of opaque black string curtains onto which Erato Tzavara’s projections and Daphne Agosin’s lighting lend the proceedings a breathtaking 3D atmosphere. Lei-Lei Bavoil, Alexandra Bråss, Andy Manjuck, Hanna Margrete Muir, Sigurd Rosenberg, Marie Skogvang Stork, Anna Soland, and Kirjan Waage, dressed in black sequined costumes that meld into the background except for their glitter, operate the puppets with great skill and more than a touch of jaw-dropping magic.

The set and costumes are by Wakka Wakka cofounding artistic directors Gwendolyn Warnock and Waage, who also wrote and directed the production; in addition, Waage designed the puppets, based on actual skeletons. Thor Gunnar Thorvaldsson’s music and soundscape, harvested from geodes and crystals and featuring bells and gongs, keep the audience immersed in the riveting narrative, which evokes the climate change, war, and greed that threaten the earth today.

The look and feel of the show were inspired by Tales from the Crypt, Dante’s Inferno, old Silly Symphonies cartoons, and the art of Hieronymus Bosch, a mix that relates to the company’s Bioeccentrism Manifesto, which states, “Life like art is hyperbolically weird, stupendous, openly ridiculous, momentary, rapid, flashy fleshy and loud,” words that can also describe Dead as a Dodo and such previous Wakka Wakka works as The Immortal Jellyfish Girl, Animal R.I.O.T., and Saga.

The show is also about our own fear of death. “When you vanish, will you forget everyone you love?” the basalt asks at the beginning. Shortly after that, the dodo pulls an alarm clock out of the rubble and it rings. “That’s just junk,” the boy says, ignoring the literal and figurative wake-up call, a warning cry to all of us that humanity is on the brink of extinction.

“What do you think happens when you disappear completely? Are you going to forget about me? Will I forget you?” the boy says to the dodo, continuing, “I don’t want to disappear. I’m not ready.”

Then again, as Emily Dickinson once wrote, “Hope is the thing with feathers / That perches in the soul, / And sings the tune without the words, / And never stops at all.”

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]