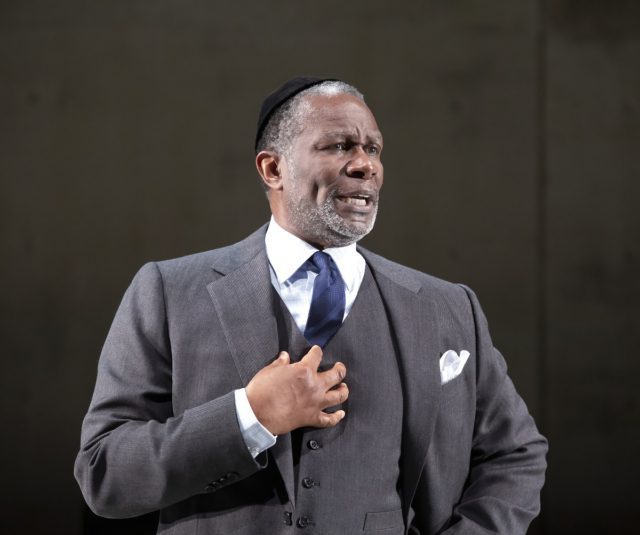

Jesse (Damian Jermaine Thompson) and Neil (Tom Holcomb) face several crises in This Bitter Earth (photo by Mike Marques)

THIS BITTER EARTH

TheaterWorks Hartford online (and in person)

March 7-20, $20 virtual, $25 – $65 in person

twhartford.org

“This bitter earth / Well, what a fruit it bears / What good is love / Mmh, that no one shares? / And if my life is like the dust / Ooh, that hides the glow of a rose / What good am I? / Heaven only knows,” Dinah Washington sings in her 1960 number one hit, “This Bitter Earth.” The song plays at the end of TheaterWorks Hartford’s production of Harrison David Rivers’s This Bitter Earth, being performed onstage and streamed on demand through March 20.

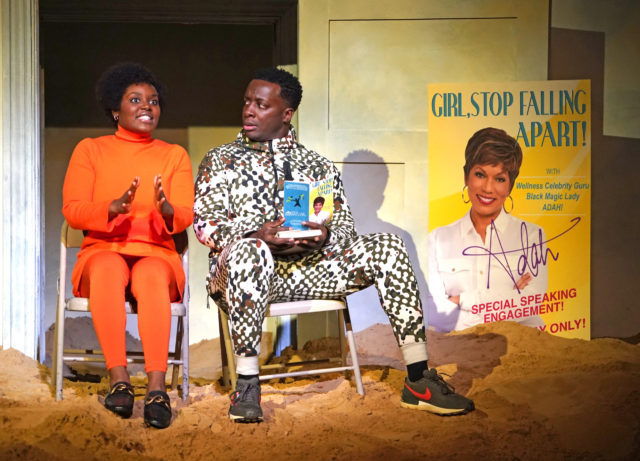

The tender and moving, if earnest, play stars Damian Jermaine Thompson and Tom Holcomb as a mixed-race thirtyish couple facing different kinds of trauma in New York City and St. Paul, Minnesota, between March 2012 and December 2015. The serious Jesse Howard (Thompson) is a Black playwright with a burgeoning career; the more outgoing Neil Finley-Darden (Tom Holcomb) is a white Black Lives Matter activist from a wealthy family. While Neil feels grounded in his life and confident in his purpose, Jesse is much more on edge; in fact, he has a troubled relationship with gravity.

“Sometimes — and scientists may refute this, but fuck them — sometimes I can feel the Earth move. And not like tremors or earthquakes, tornados or hurricanes. This is not a matter of wind or tectonic plates but rather a matter of chemistry. Body chemistry. My body chemistry,” Jesse says in one of numerous short monologues he delivers directly to the audience. “I find it strange that others can’t feel it — the rotation. Strange and a bit lonely.”

The play takes place in their spacious Harlem bedroom, with large windows that often show snow falling, a coldness hovering over everything. (The attractive set is by Riw Rakkulchon.) “It’s the way that history isn’t history at all. Or, at least, the way that it doesn’t stay in the past. The way that the past fucks the present,” Neil tells us. The narrative goes back and forth in time, from when Jesse and Neil first meet and fall for each other, to the current day, amid several tragedies. Each flashback adds a bit more to the story, further developing the characters and certain key aspects of the story, which revolve around the murders of innocent Black men at the hands of white police officers and other citizens, from Trayvon Martin and Michael Brown to Jamar Clark and the Charleston church shooting.

Tom Holcomb and Damian Jermaine Thompson star as lovers who look at the world differently in TheaterWorks Hartford production (photo by Mike Marques)

But Rivers offers a neat twist on expectations, as Neil seems more intent on doing something about it than Jesse does. “You know, you accuse me of my white guilt, but what about yr apathy?” Neil declares as he prepares to take a van to a protest in Ferguson, Missouri. Jesse explains that he can’t go because he has rehearsals. “You know, yr not the center of the universe, Jesse. No one has that kind of gravitational pull. Not even you,” Neil says before leaving.

Their fights, which are no different from those of straight couples of the same race, often end in loving embraces, with clothes coming off as they roll around on the bed; their passion is evident throughout, even with their distractions. (There’s plenty for fight and intimacy director Rocío Mendez to do, as well as costume designer Devario D. Simmons.) But a common theme keeps arising, that of Jesse’s desire to live life like a regular person, whatever that is these days. “Yr a fucking double minority, Jesse,” Neil says, to which Jesse responds, “What does that have to do with anything?” Be sure to bring tissues for the conclusion.

Affectionately directed by David Mendizábal (Tell Hector I Miss Him, On the Grounds of Belonging) with almost too much thoughtful understanding, This Bitter Earth is a sensitive story of love in difficult times. The stream is well shot with multiple cameras in front of an audience, feeling like a theatrical work and not a film. The show, which premiered in 2017 at San Francisco’s New Conservatory Theatre Center, is even more cogent today, with the murders of Elijah McClain, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and so many others occurring since the play’s debut. Rivers (Broadbend, Arkansas; When We Last Flew) has Jesse quote extensively from gay Black poet and activist Essex Hemphill, a hero of Jesse’s and, apparently, the playwright’s; the story works much better when Jesse speaks for himself.

Thompson (Fly, The Brother/Sister Plays) and Holcomb (London Assurance, Transport) have a sweet chemistry; you can’t help but root for Jesse and Neil through their hardships, trying to survive, as individuals and as a couple, in a world that needs to be seen as more than just black or white, straight or gay, male or female. As Washington sings, “Oh, this bitter earth / Yes, can it be so cold? / Today you’re young / Too soon you’re old / But while a voice / Within me cries / I’m sure someone / May answer my call / And this bitter earth, ooh / May not, oh, be so bitter after all.”