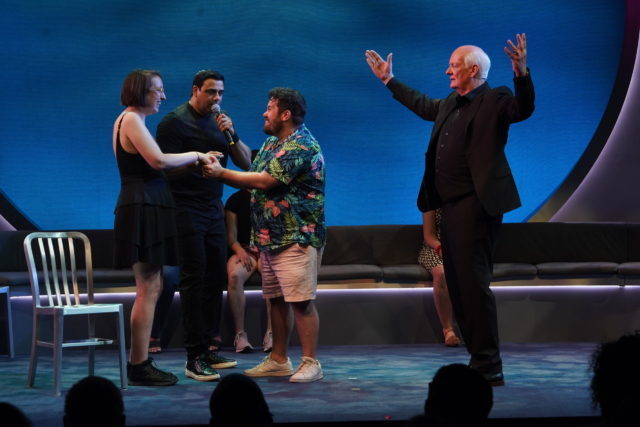

Volunteers fall under the spell of master hypnotist Asad Mecci in HYPROV (photo by Carol Rosegg)

HYPROV

Daryl Roth Theatre

103 East 15th St. between Irving Pl. & Park Ave.

Wednesday – Sunday through October 30, $55-$195

www.hyprov.com

There’s a curious aspect to ticket prices for HYPROV: Improv Under Hypnosis, which opened tonight at the Daryl Roth Theatre. The highest-priced tickets are in the first row and on the aisle in the lower rows, nearly double the price in the second row center. After seeing the hilarious show, I understand why.

HYPROV, a combination of hypnosis and improvisational comedy, has been traveling across the US and Canada, along with stops in England and Scotland, since 2016. Canadian master hypnotist and motivational life and performance coach Asad Mecci contacted Scottish-Canadian improv legend Colin Mochrie via an email he sent through the comedian’s website. Mochrie’s manager, Jeff Andrews, discussed the idea with Mochrie and HYPROV was born.

The evening begins with Mecci describing to the audience what they’re in for. Twenty volunteers will come onstage and be hypnotized, locking out their brain’s penchant for self-reflection and embarrassment so the participants will be much less inhibited and able to invest themselves fully in improv comedy sketches. No one will be made to do anything they don’t want to do; instead, they’re so relaxed that they can release their inner performer. Mecci whittles down the twenty volunteers to about five who will then be part of the main show.

So, back to the ticket prices. When Mecci announces that anyone interested in being hypnotized should come to the stage, there’s a mad dash from all over the theater. Thus, if you are sitting in the front row or the lower aisle seats, you have a much better chance of making the twenty-person cutoff than someone sitting, say, in the middle of the twentieth row. My guess is that those paying the premium price are determined to make it to the stage; a woman in the center of my row hesitated just enough to miss the cut by a few people. But no worries; like the rest of us, she was about to have a rousing good time nevertheless.

Asad Mecci and Colin Mochrie set up the next scene in hypnotic improv show at the Daryl Roth (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Part of the fun is watching the muscle-bound Mecci, who studied under hypnotist Mike Mandel and life and business strategist Tony Robbins, do his thing as you try to predict who he will ultimately select. He tests how relaxed and hypnotized the volunteers are by putting them in a few unusual situations; he doesn’t make anyone bark like a dog or act like a chicken, but he does have them search for one of their missing body parts. The night I went, he asked one of the volunteers why he needed it. “Because my mother gave it to me,” he responded, as if it were a family heirloom. He made the cut.

After Mecci chooses that evening’s cast, Mochrie, who has been a regular on several iterations of Whose Line Is It Anyway? for more than twenty-five years, working with Ryan Stiles, Wayne Brady, Greg Hoops, and Brad Sherwood (as well as hosts Drew Carey and Aisha Tyler), takes over. For the next hour or so, Mochrie selects a series of scenes — there are about ten standard setups in the repertoire, with more to be added — and asks the audience to call out prompts, from locations and professions to animals and props. Mecci throws in an extra twist by deciding which of the hypnotized cast will play what role.

Then the sketches unfurl, with Mochrie ready to pick up any pauses and Mecci holding the mic for the volunteers while making sure they don’t snap out of their trancelike state and, even more important, don’t cross any barriers, either psychological or physical. For example, when one young man began a surprisingly entertaining dance, mixing contemporary with ballet, Mecci watched closely to make sure he wasn’t going to whack anyone in the head or take an unintentional dive off the stage. In another scene, two characters were in the midst of a romantic moment when Mecci jumped between them right before they were about to kiss. “That was a close one,” Mochrie acknowledged. Mecci, who has to be careful not to become too much of an audience member himself — he tries his best to contain his own outbursts of laughter — heartily agreed.

Mochrie, who was one of the first popular social media gifs, appears to be having a ball through it all, though he admits that it is scary for him too; he’s used to working with trained professionals, so his instincts have to be even quicker here with the amateur comedians. He also had to sing, quickly noting that music is not his forte, but the hypnotized woman he duetted with knocked it out of the park.

Speaking of music, Rufus Wainwright, who was born in New York but raised in Montreal, has composed an original score for the induction scene, a steady, breathy drone that is heard as the volunteers are being hypnotized. (Mecci had helped Wainwright’s husband quit smoking through hypnosis.) Meanwhile, music director John Hilsen sits off to stage left, improvising at the keyboards as the scenes play out.

Just about anything can happen in HYPROV, with a few important exceptions (photo by Carol Rosegg)

The line of the night didn’t come from Mecci or Mochrie but instead from one of the volunteers who, while portraying a sound effects engineer for an old-time radio show who gets each noise wrong, called out in a high-pitched voice when he was cued for an owl: “owwwwwwwwlllllllll noooooooooooiiiiiiiiiiiise!”

Jo Winiarski’s set features a giant circle on the back wall, right behind a curved bench where the volunteers sit when not part of the show. The colors on the circle change ever so slowly, with a calming effect; the lighting designer is Jeff Croiter, with sound by Walter Trarbach. Longtime television writer and producer Stan Zimmerman (The Gilmore Girls, A Very Brady Sequel) is left with the near-impossible task of directing a production that thrives when it veers toward a certain amount of chaos.

While there are sure to be skeptics who think that at least some of the volunteers have to be plants, Mecci and Mochrie declare that they have never before met any of the people who have made it onstage, and I spoke with two of the participants after the show who both assured me that it was all legit, that they were aware all the time exactly what they were doing but free of any lack of self-esteem or worry that they would embarrass themselves in public.

HYPROV can be a little ragged at times, and there are occasional hiccups and lapses as the improv sketches get under way, but the show is a tribute to what we are all capable of, persuading each of us that maybe we should get on the stage next time and give it a go. Maybe you’ll come home having delivered the line of the night — but you’ll probably need to splurge for those more expensive seats.