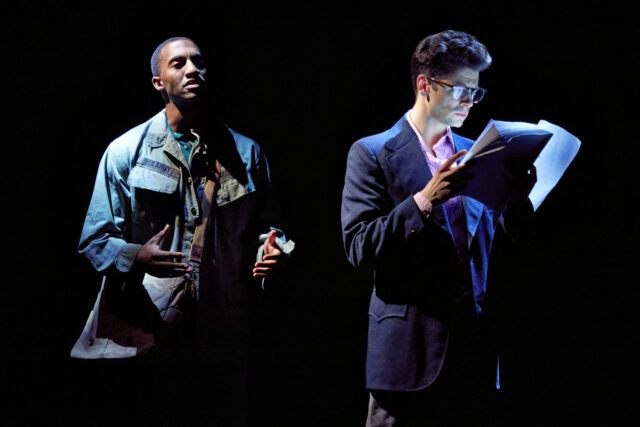

An Astoria tailor shop is the setting for Christina Masciotti’s No Good Things Dwell in the Flesh (photo by Maria Baranova)

NO GOOD THINGS DWELL IN THE FLESH

Jeffrey and Paula Gural Theatre

A.R.T./NY Theatres

502 West Fifty-Third St.

Wednesday – Sunday through September 23, $34.12

www.christinamasciotti.com

There’s a loose thread dangling through much of Christina Masciotti’s No Good Things Dwell in the Flesh, hanging in there until it’s finally pulled and the previously moving play comes undone.

The show is set in 2019 in a tailor shop in Astoria run by Agata Priechev (Kellie Overbey), a straightforward Soviet immigrant. She has hired Janice (Carmen Zilles), one of her students at FIT, as her apprentice. Janice, from a family of Brazilian descent, is approaching thirty, and while Agata is teaching her how to be an expert seamstress, Janice is getting advice that translates as life lessons as well.

Agata’s devotion to and love of her craft makes tailoring a vocation, more than a job, and she does her best to call Janice to that as well. “Everybody knows dying profession. It’s dying because it’s hard way to learn and you have to be creative. People doesn’t wanna learn. It’s time taking. Again, again until perfection,” Agata says in her broken English. “You never see young people working in alterations. You can be lawyer or doctor in ten years. Can’t be alterations in ten years. Now click on internet, make a lot of money. With this you can’t just click, you have to work a hundred years. I prefer this but. Last week, I was stitching so many things, I fell asleep on my couch. Tomorrow will be third, I have to do jacket, two things will go home with me. At home I don’t have that spare of a moment. I can’t continue like this. All of a suddenly, I realized in twelve years I had one vacation. I’m sixty-four. Life will be over soon. I need a vacation.”

Agata, who has a daughter living in London, has decided to take more than just a vacation; she wants to retire and give the shop to Janice, who isn’t sure she’s up to the responsibility and the commitment. Janice has trouble putting down her cell phone and is busy trying to find the right man to settle down with. While she starts dating an old high school friend, Agata is being harassed by Vlad (T. Ryder Smith), a Romanian man from Venezuela who has been obsessed with her since they met at Bloomingdale’s twelve years earlier. Vlad, who could be an Eastern European spy, a sexual predator, or an immigrant with mental health issues, shows up at odd times, asking for strange alterations and making unfounded accusations. Agata remains steadfast, as if Vlad is part of the unhappy old days that she has put behind her. “The past is dead body in basement,” Agata tells Janice.

As Janice weighs her future with Eddie, Agata fights off Vlad, grumpily refuses to take on jobs she doesn’t want to do, and attempts to prepare Janice to take over the business.

Vlad (T. Ryder Smith) is obsessed with Agata Priechev (Kellie Overbey) in No Good Things Dwell in the Flesh (photo by Maria Baranova)

The title of Masciotti’s 105-minute play (without intermission) was inspired by a quote from the apostle Paul about law and sin: “For I know that nothing good dwells in me, that is, in my flesh. For I have the desire to do what is right, but not the ability to carry it out.” The three central characters — Jeffrey Brabant, Annie Fang, and Megan Lomax appear in multiple minor roles, portraying various customers and police officers — all desire to do what is right, but various factors make them unable to, preventing them from flourishing.

Director Rory McGregor (Buggy Baby, Interior) can’t quite weave all the materials together into a satisfying whole. Brendan Gonzales Boston’s set is open on several sides, making it difficult to understand the geography surrounding the tailor shop, especially near the end, when characters start walking through areas that previously seemed to be invisible walls.

A rack of clothes hanging from above in the back is a deft touch, as if representing Agata’s achievement over the years. Given the setting, Johanna Pan’s costumes are not exemplary, although I’m still a bit creeped out by Vlad’s preference for mandals no matter what else he’s wearing. The steady lighting is by Stacey Derosier, with sound by Brian Hickey.

The next line of the Bible quote, from Romans 7:19, reads, “For I do not do the good I want, but the evil I do not want is what I keep on doing.” The title and the biblical quotes that relate to it are both compelling, but the narrative doesn’t live up to that promise. No Good Things Dwell in the Flesh is not a tale of good and evil as much as it is a story of characters in search of a happiness they’re not sure they deserve. Masciotti (Raw Bacon from Poland, Social Security) leaves too many threads untied, too much unused cloth on the cutting-room floor.

Overbey (Love and Information, Mary Page Marlowe) is firm and direct as Agata, a woman who doesn’t know how to be happy. “Tailor are special people,” she tells Janice. “You know it’s dying profession.” Zilles (Epiphany, Fefu and Her Friends) imbues Janice with a kind of wide-eyed wonder, not yet ready for what the world can offer her. Smith (The White Devil, Oslo) plays Vlad with a nervous jitteriness that will make you uncomfortable in your seat.

No Good Things Dwell in the Flesh start off with a good pattern but, in the end, could have used more custom tailoring and alterations.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]