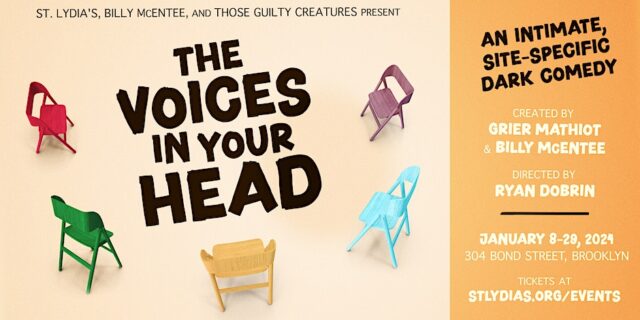

The Whole of Time offers a new look at Tennessee Williams’s The Glass Menagerie (photo by Maria Baranova)

THE WHOLE OF TIME

Torn Page

435 West Twenty-Second St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves.

Thursday – Monday through January 27, suggested donation $44

www.tornpage.org

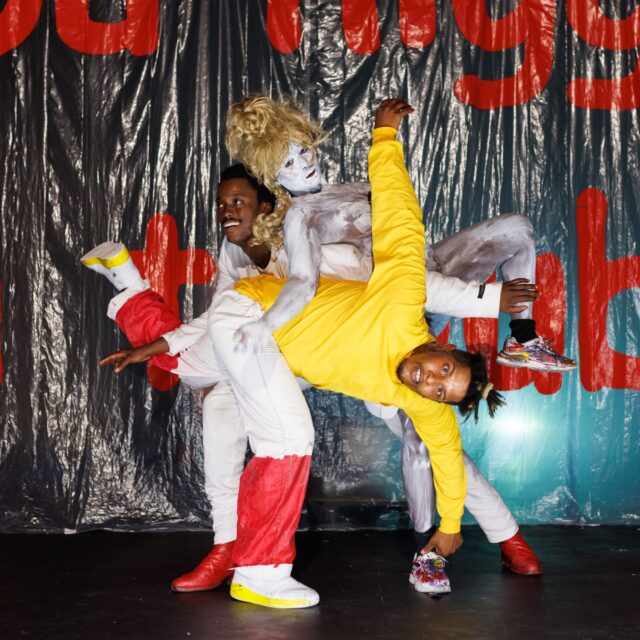

About halfway through the US premiere of Argentinian playwright Romina Paula’s The Whole of Time, there’s a powerful, poignant scene between Antonia (Josefina Scaro), a young woman who prefers to spend her life inside her family’s house, and Maximiliano (Ben Becher), a leather-jacketed macho friend of her brother’s.

When Maximiliano asks her what she does with her life, she replies, “Oh, nothing.” Startled, he says, “What do you mean nothing?” She answers, “Yeah, nothing. At least according to the terms you’re asking me, nothing.” She tells him confidently that she doesn’t work or go to school. “You must do something,” he presses. She responds, “No, I don’t believe in doing.” Her younger brother, Lorenzo (Lucas Salvagno), who is reading Moby-Dick, calmly explains, “Antonia doesn’t go out.”

Lorenzo exits, and Maximiliano continues to ask her about her lifestyle choice, which he cannot understand. “This is who I am, I’m this way,” she declares. He asks, “But don’t you think it’s sad?” They disagree over what’s considered free or wasted time and what happiness is. As they move in closer to each other, she puts on Rata Blanca’s “La leyenda del hada y el mago,” a song about magic, love, and loneliness in a fairy-tale world.

Lorenzo and then their mother, Ursula (Ana B. Gabriel), enter, cutting off whatever might have been happening between Maximiliano and Antonia. “Oh, thank God you’re alive!” Ursula proclaims. Lorenzo interjects, “Awake, Mom. Thank God we’re awake.”

Unfortunately, that’s the only scene with any life to it; the rest of the play is a befuddling snooze.

Ben Becher and Josefina Scaro bring the heat to The Whole of Time (photo by Maria Baranova)

Translated from the original Spanish by Jean Graham-Jones, The Whole of Time is a contemporary reimagining of Tennessee Williams’s memory play The Glass Menagerie, but it goes way off track. It takes place in a small rectangular room at Torn Page, the Chelsea home where actors Rip Torn and Geraldine Page lived. Torn and Page starred onstage and onscreen in Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth and were friends with the two-time Pulitzer Prize winner (for A Streetcar Named Desire and Cat on a Hot Tin Roof). An audience of no more than twenty-two people sit in two rows of folding chairs on one side of the room, across from the set that features a table where Antonia spends time on her laptop, an old armchair where Lorenzo reads, a fireplace, a vanity table, and a chifforobe; the back wall is a swriling blue, evoking Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul in Mexico City. The set and video design is by Tony Torn, Rip and Geraldine’s son, who also directs the play; Donald Gallagher painted the backdrop.

It begins with a discussion about Mexican artist Marco Antonio Solís’s song “Si no te hubieras ido” (“There’s Nothing More Difficult Than Living without You”) that leads them to Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair and talk of murderers. Projections on the back wall above the fireplace include a video of Solís performing his song and images of works by Kahlo, including the self-portrait and Portrait of My Father. The family lives in Argentina but Antonia and Lorenzo were born in Mexico; Ursula is from Hungary, which Antonia notes is like Kahlo’s father, photographer and painter Guillermo, who was born in Germany, died in Mexico, and might or might not have had Hungarian-Jewish roots. (Frida claimed he did, whereas a 2005 book debunked that using genealogy studies.)

Scaro, who strongly resembles Sarah Silverman and is the cocurator of events at Torn Page, is terrific as Antonia, a young woman not realizing that she has trapped herself; instead of having a limp like Laura in The Glass Menagerie, her physical affliction is represented by her obsession with Kahlo, who suffered severe injuries in a bus crash when she was eighteen and lived in terrible pain the rest of her life. Becher, who also serves as the preshow bartender, is seductive and charming as Maximiliano — the gentleman caller — a tough guy with a tender heart who just wants to enjoy life. Salvagno and Gabriel do what they can with their indistinct characters, he playing a calm, unassuming son and she a mother who still wants to dance and party, trying to find quick happiness that remains elusive. There’s a pall over the family, but it’s not the abandonment of the patriarch that hovers over Menagerie.

Jay Ryan’s lighting design is sparse, usually the standard lighting in the room, with occasional turns into darkness. Torn was sitting in one corner, often checking his cell phone, next to stage manager Berit Johnson, who works tech, which can be distracting if you’re sitting nearby. At one point, two characters were on either side of the space, engaged in a conversation that made audience members swivel their heads back and forth like they were watching a lackadaisical tennis match. There are a couple of avant-garde touches, but they feel out of place. Even at a mere seventy minutes, the production lags, meandering in and out of the story in confusing ways.

In The Glass Menagerie, Tom tells the audience, “Yes, I have tricks in my pocket, I have things up my sleeve. But I am the opposite of a stage magician. He gives you illusion that has the appearance of truth. I give you truth in the pleasant disguise of illusion.” That’s precisely what’s missing from The Whole of Time.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]