Caryl Churchill’s Glass. takes place on a glowing, floating platform (photo by Joan Marcus)

GLASS. KILL. WHAT IF IF ONLY. IMP.

Martinson Theater, the Public Theater

425 Lafayette St. at Astor Pl.

Tuesday through Sunday through May 25, $89

212-539-8500

publictheater.org

British playwright Caryl Churchill burrows into the fragility of human life and the concept of impermanence in Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp., four short works being performed together at the Public’s Martinson through May 25.

For more than fifty years, Churchill, now eighty-six, has been writing inventive, experimental plays that challenge audiences through abstract narratives and unique, unexpected stagings, from Cloud Nine and Top Girls to Vinegar Tom and Love and Information, creating her own genre, with flourishes of Beckett, Pinter, and Brecht mixed in. The four-time Obie winner has penned more than fifty works for the stage, radio, and television; three of the pieces at the Public were written in 2019, the fourth in 2021. (Glass., Kill., and Imp. were originally performed with Bluebeard’s Friends at the Royal Court Theatre in September 2019 but has been replaced here by What If If Only, her latest play.)

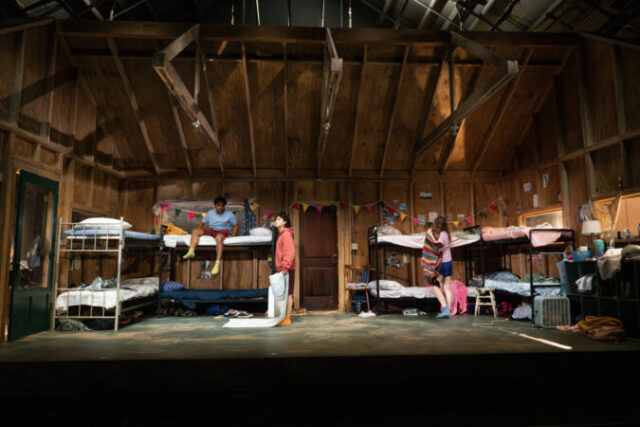

The 135-minute show (with intermissions) is a triumph for both Churchill and Miriam Buether, whose breathtaking sets lift Churchill’s themes to the next level, along with stunning lighting by Isabella Byrd and compelling sound by Bray Poor, making it a visual and sonic treat. First up is Glass., which unfolds on a glowing rectangular platform hanging in the middle of the space, surrounded by darkness. It’s a kind of mantel where a Girl Made of Glass (Ayana Workman), a Clock (Sathya Sridharan), a Vase (Japhet Balaban), and a Red Plastic Dog (Adelind Horan) interact, attempting to define their existence and importance.

“She doesn’t want to be touched. She’s afraid of being broken,” the Girl’s protective mother says, explaining how there are many cracks in her daughter, who needs bubble wrap to go out.

The defensive Clock tells the Girl, “You’re beautiful but I’m also useful.” The Girl responds, “A clock isn’t useful anymore. Who looks at you? Time’s on the phones.” The Clock answers back, “They look at me because I’m worth looking at. Time from me is richer because I’m old and time’s run through me since before their parents were born. And you see it flow because my second hand goes round and my minute hand goes round and my hour hand goes slowly round and there’s none of this digital jumping. You gaze at me and think how long a minute lasts. Pain for a whole minute would be torture. Joy for a whole minute would be exceptional. And even if I stopped I’d be kept as an object because my history is intriguing and my shape is graceful and my value is unquestioned.”

The Dog says she is a reminder of happy times, even if she’s dusty and hasn’t been played with in years. The Vase is thrilled when the Girl says he is beautiful even without flowers. A group of schoolgirls stop by and taunt the Girl. A friend tells her a secret.

The play ends with a moving monologue in which the Girl expresses her fears in a way we can all relate to, how easy it is to become physically and emotionally damaged.

During the first break, hand balancer Junru Wang performs remarkable feats on canes in the pit in front of the stage as the set is changed behind the red velvet curtain. Wang pushes herself high into the air, stretching, switching hands, and contorting her limbs, a dazzling display of what the human body is capable of, a thrilling counterpoint to the delicate Girl Made of Glass.

Deirdre O’Connell relaxes on a cloud while talking about death in Kill. (photo by Joan Marcus)

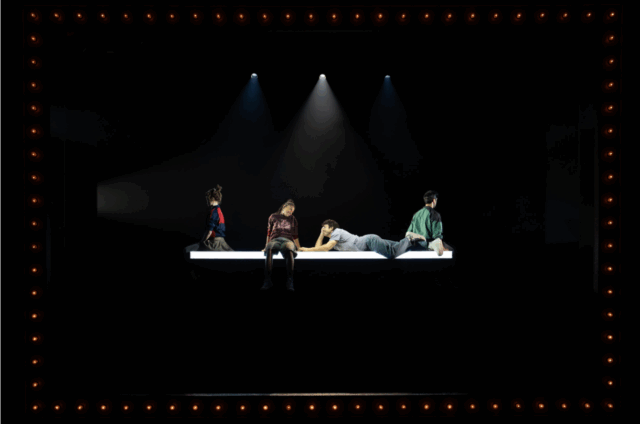

In the solo Kill., Tony winner Deirdre O’Connell, wearing all white, sitting comfortably on a floating cloud in a black sky, delivers a treatise on the gods’ power over humans, treating them as playthings as they watch them murder one another as if orchestrating a Greek tragedy for fun. Fathers, mothers, husbands, brothers, cousins, lovers, and kings are brutally murdered, sent to hell, eaten, brought back for more punishment — it’s a vicious cycle of death and destruction put on for pleasure, a sly comment on the theater itself as well as the violence inherent in everyday life.

She begins, “We take this small box and shut the furies up in it, they’re furious and can’t get out, they say let us out and we’ll be kind. We gods can do that sometimes, quieten the furies, we can’t do everything, we don’t exist, people make us up, they make up the furies and how they bite. They’re after the boy, they won’t let him sleep or wake or sleep and he suffers. He suffers and suffers because he kills his mother, which we’re against and so is everyone but he has his reason so he’s right and wrong. He kills his mother, hoping she’ll die quickly, it can’t be over quickly enough, he doesn’t want her unrecognisable but still here, both slipping in the blood, his duty to do it, everyone thinks that and so do we, and he kills her lover happy to kill him but taking out the knife he remembers loving his mother and the nonsense words they’d say to each other though he still has the same hate in his heart coming home as when he’s little and runs away when she’s killing his father.”

It’s a tour de force for O’Connell, the words spilling out in a nonstop poetic assault that underlines humanity’s penchant for real and fictional violence; Churchill also questions the notion of faith, people’s belief that someone else is pulling the strings, be it a supreme being or, perhaps, a playwright, from Ancient Greece or twenty-first-century England. As the god says multiple times, “We don’t exist.”

During the second break, Maddox Morfit-Tighe juggles clubs, involving a few audience members; it’s not as awe-inspiring as what Wang did, and the metaphor is more obvious, but it is still entertaining as the stage is prepared for the third tale.

A man (Sathya Sridharan) faces loss in What If If Only. at the Public (photo by Joan Marcus)

What If If Only. is set in a mysterious large white cube reminiscent of Churchill’s Love and Information. A man identified in the script as Someone on Their Own (Sridharan) is sitting at a small table with a bottle of wine and two chairs; it is apparent that he is waiting for a person who is unlikely to come.

“If I was the one who was dead would you still be talking to me? We once said if one of us died if there was any way of getting in touch we should do it, I thought we’d be old. Are you not trying?” he says. “If you’d wanted to talk to me you could have stayed alive. I’ve nothing to say really, I just miss you. I once thought I saw a ghost, not spooky like Halloween, just a wisp of something standing in the door. I’ve told you this already, do you remember? Is remembering something you can do or has it all gone now? I miss you I miss you I miss you I miss you. I miss you. Please, can you? Just a wisp would be fine. If you can, please. Please, I miss you. A small thing, just any small thing, let me know you’re there somewhere. If you can.”

A woman (Workman) does arrive, but the man is not sure what or who she is. They agree she is at least a little like his lost love, then talk about regrets and possibilities, living and dying. She tells him, “I’m the ghost of a dead future. I’m the ghost of a future that never happened. And if you can make me happen then there would be your beloved real person not a ghost your real real living because what happened will never have happened what happened will be different will be what you want will be a happy happy.”

Soon the walls of the white cube rise and others enter, including a young girl (Cecilia Ann Popp), Asteroid, Empire, Silver, Nature, Small, and a calm, supportive older man (John Ellison Conlee) who tries to help the younger man face the reality of his situation, that there are so many futures but only one that will happen. It’s a gorgeous existential conversation with a surprise conclusion.

Imp. concludes quartet of existential works by Caryl Churchill (photo by Joan Marcus)

Imp. follows a full intermission (without acrobatics), featuring another brilliant set, this time a raggedy living room with a couch, a comfy chair, a floor lamp, and a red oriental rug on a slanted platform. It is the home of nonkissing cousins Jimmy (Conlee) and Dot (O’Connell), who bicker like an old married couple with nothing better to do. While the widowed Jimmy occasionally gets up to go running, training for a half marathon, the divorced Dot never leaves her chair.

Their several-times-removed Irish niece, Niamh (Adelind Horan), was recently orphaned, so she is visiting Jimmy and Dot while making a new life for herself in England. When Niamh says she needs to lose a stone by summer, Dot disagrees and says, “You’re lovely how you are. Don’t do it.” Jimmy argues, “Leave her alone, goals are good, you want everyone not to be fit so they’re no better than you. Just like you want everyone to be miserable.” Dot barks back, “You’re fattist is what he is, not he’s the fattest, Niamh, I mean like racist.” It’s rarely easy to parse Dot’s logic.

Another day they are speaking with the homeless Rob (Sridharan), a world traveler who’s been sleeping in a cemetery, wanting to go back to his son and estranged wife. The ever-suspicious Dot worries that if they let him stay in their house, he might kill them and take the residence for himself. “Why would he want to do that? He’s not stupid,” Jimmy says. Dot replies, “But if he could get away with it and have the flat. Don’t tell me you’ve never thought it.” Rob deadpans, “I’ve never thought it.” Soon Dot and Jimmy are hoping that Niamh and Rob get together.

They delve into faith and religion, with Niamh wondering what being Catholic ever did for her except make her terrified of sin and hell. Dot, a former nurse, is afraid of her temper, which might have cost her her marriage and career. Rob is deeply worried about his immediate future. Meanwhile, Jimmy is an eternal optimist.

But when Jimmy tells Rob about the bottle Dot keeps that she claims has a wish-giving imp in it, new questions arise about what’s next.

There might be a period after the name of each part of Glass. Kill. What If If Only. Imp., but they form a cohesive whole in this stellar production, gorgeously directed by longtime Churchill collaborator James Macdonald (Infinite Life, Escaped Alone). In three of the four plays, the characters wear Enver Chakartash’s casual, naturalistic costumes (O’Connell is in heavenly garb in Kill.), equating them with the audience, making the otherworldliness more believable. The pain of loss, the brittleness of life, the lack of power humans have over their destiny hover over all four plays. In each one, there is also trepidation about the future of each character, the sets tilted and suspended in ways that make it seem like the actors could at any moment fall off into the darkness or be trapped in blazing white light.

Churchill and Macdonald practically implore us to take a look at ourselves and examine how we deal with faith, grief, and, perhaps most important, time. “I sit on the mantelpiece and time goes by,” the Girl says in Glass. The characters in the other three works also are often sitting down, not taking action but watching and waiting.

It’s enough to force you to face your own future once you get out of your theater seat and venture back into the real world.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]