Becky (Keala Settle), Jenna (Jessie Mueller), and Dawn (Kimiko Glenn) serve pies and more in WAITRESS (photo by Joan Marcus)

Brooks Atkinson Theatre

256 West 47th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 1, $69-$159

877-250-2929

waitressthemusical.com

www.brooksatkinsontheater.com

Tony-winning star Jessie Mueller has quickly become one of those Broadway sensations you can watch do just about anything, even when she serves up a dish of lukewarm Lifetime schmaltz like Waitress. Mueller, who has risen well above her material in Beautiful: The Carole King Musical and On a Clear Day You Can See Forever, does the same in this American Repertory Theater musical, an adaptation of Adrienne Shelly’s 2007 film, which was accepted to Sundance shortly after Shelly was murdered in Greenwich Village at the age of forty. Mueller plays Jenna Hunterson, a waitress in Joe’s Pie Diner, where every morning she makes such delectable, original delights as Marshmallow Mermaid Pie, Fallin’ in Love Chocolate Mousse Pie, and Jenna’s First Kiss Pie. “You want to know what’s inside? Simple question, so then what’s the answer?” she sings. “My whole life is in here, in this kitchen baking.” Desperate to escape an abusive marriage to Earl (Nick Cordero), she is distraught to learn she’s pregnant. When diner owner Joe (Dakin Matthews) suggests she compete in a pie contest with a prize of twenty thousand dollars, she thinks she may have discovered her way out, but her life gets even more complicated when she becomes attracted to her new gynecologist, the married Dr. Pomatter (Drew Gehling). Her coworkers, the sharp-tongued Becky (Keala Settle) and the wallflower Dawn (Kimiko Glenn, in the role played by Shelly in the movie), provide emotional support and comic relief, while Jenna’s coping skills include memories of baking pies with her late mother and imagining what she’ll make next, creating in her mind such telling desserts as I Don’t Want Earl’s Baby Pie, Betrayed by My Eggs Pie, and I Can’t Have an Affair Because It’s Wrong and I Don’t Want Earl to Kill Me Pie. But Jenna can’t stop spending time with Dr. Pomatter despite knowing better. “It’s a terrible idea me and you,” they sing in a duet. Jenna: “You have a wife.” Dr. Pomatter: “You have a husband.” Jenna: “You’re my doctor!” Dr. Pomatter: “You’ve got a baby coming.” Both: “It’s a bad idea me and you / Let’s keep kissing till we come to.” Unfortunately, by the time they come to, it’s too late.

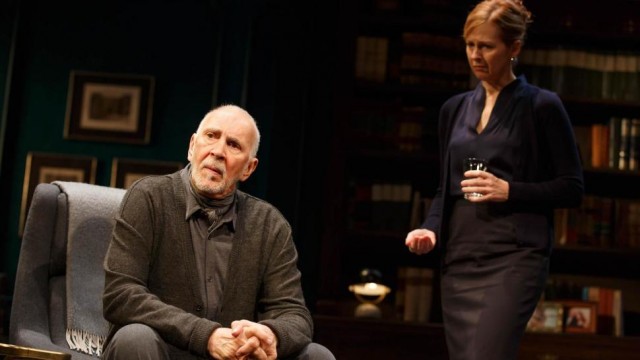

Dr. Pomatter (Drew Gehling) and Jenna (Jessie Mueller) seek a sweeter life in adaptation of Adrienne Shelly’s 2007 romantic comedy (photo by Joan Marcus)

Mueller shines once again in Waitress, making the most of what is essentially a hard-to-believe contemporary bodice ripper disguised as a romantic musical comedy. She has a comforting stage presence, blending confidence and vulnerability in charming ways, even as we watch her character make absurdly ridiculous decisions. She, Settle (Hands on a Hardbody, Priscilla Queen of the Desert), and Glenn (Orange Is the New Black, Yoshimi Battles the Pink Robots) share a warm camaraderie, recalling the trio of waitresses from the television series Alice, along with Eric Anderson (Soul Doctor, Kinky Boots) as Cal, the gruff cook. Christopher Fitzgerald (Young Frankenstein, Finian’s Rainbow) nearly steals the show as Ogie, going all out as a stalker-like major nerd who is interested in Dawn and is not afraid to let everyone know about it. His stirring rendition of “Never Ever Getting Rid of Me” is a genuine showstopper. The songs, by five-time Grammy nominee Sara Bareilles, are relatively harmless, mixing in multiple genres, but former waitress Jessie Nelson’s (I Am Sam; Corrina, Corrina) book never really gets cooking, jumping around too much while taking underdeveloped or overdone turns. Director Diane Paulus (The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess, Hair, Pippin) does what she can with the mediocre material, wisely making sure that Mueller is front and center as much as possible on Scott Pask’s set, which changes from the diner to the doctor’s office to Jenna and Earl’s home. Waitress serves up a few very tasty slices, but it takes more than that to make a wholly satisfying pie.