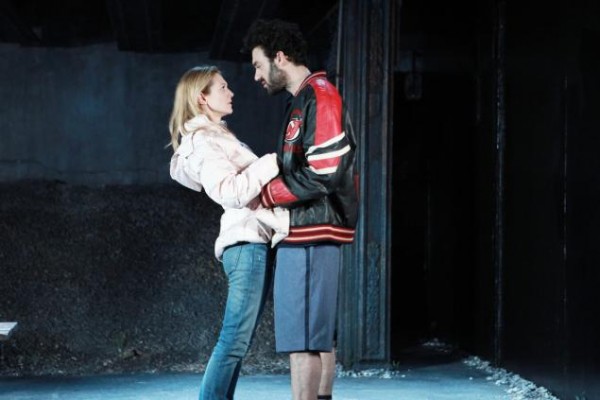

Carmen Cusack belts away on moving set in dazzling Broadway debut in BRIGHT STAR (photo by Nick Stokes)

Cort Theatre

138 West 48th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through June 26, $45 – $115

brightstarmusical.com

The opening number of the new Steve Martin and Edie Brickell musical, Bright Star, takes a chance right from the start, putting its cards on the table as Alice Murphy (Carmen Cusack) declares, “If you knew my story / My heaven and hell / If you knew my story / You’d have a good story to tell.” It turns out that Bright Star does have a pretty good story to tell, for the most part, and it does so with an intoxicating homey style and sweet sense of humor. The fairy-tale-like narrative, with its fair share of darkness, shifts between the 1920s and 1940s in North Carolina. In 1945, Billy Cane (AJ Shively) has returned home from the war with a jump in his step but is saddened to learn from his father (Stephen Bogardus) that his mother has recently passed away. Determined to become a writer, Billy has been sending his stories to his childhood friend Margo Crawford (Hannah Elless), who owns the local bookstore. Now grown up, she has taken a more romantic interest in Billy, who is oblivious to her desires; he decides to move to Asheville to try to get his writing published in the prestigious Asheville Southern Journal, which will be no easy feat, as it is run by notoriously difficult editor Alice Murphy and her two gatekeepers, the snarky and sarcastic Daryl Ames (Jeff Blumenkrantz) and the sexy and alluring Lucy Grant (Emily Padgett). When Billy first arrives at the company, Daryl tells him that the New Yorker wanted to steal Miss Murphy away, but Lucy notes that the dour editor wanted to stay in North Carolina. “That’s good!” Billy cries out. “Not for young tadpoles like you,” Daryl says. Lucy adds, “She once made Ernest Hemingway cry. He lay right there, banged his fists on the floor, and sobbed.” Billy asks, “Why?” to which Lucy replies, “He used the word ‘their’ as a singular pronoun.” The story then jumps back to sixteen-year-old Alice (Cusack) in 1923 and her flirtation with twenty-year-old Jimmy Ray Dobbs (Paul Alexander Nolan), the hunky son of Mayor Josiah Dobbs (Michael Mulheren). But the mayor, a big-time businessman of the Old South, has other plans for his son, preparing to marry him off to help the company. However, Jimmy Ray wants to go to college and experience the world outside Zebulon. “You can’t expect the future to be just like the past / You haven’t got a clue, sir, please try to understand,” Jimmy Ray sings. “When I stood tall, side by side with your grandpa / There was just nothing at all we couldn’t do,” his father responds. Soon the two main plots merge, leading to a surprise conclusion that is not quite as shocking as it thinks it is but is heart-wrenching nonetheless.

Part of band spends entire show in mobile cabin in musical by Steve Martin and Edie Brickell (photo by Nick Stokes)

Actor, musician, novelist, comedian, and playwright Martin (Picasso at the Lapin Agile, Shopgirl) and folk-rock musician Brickell — billing themselves as the new Steve and Edie — collaborated on the music and story, inspired by an actual event; Martin wrote the book, while Brickell wrote the lyrics. (The musical was initially based on their 2013 album, Love Has Come from You, but went through major changes, leading to their 2015 follow-up, So Familiar, which includes their versions of many of the songs that made the final show.) Director Walter Bobbie (Chicago, Venus in Fur) and choreographer Josh Rhodes (Rodgers & Hammerstein’s Cinderella, It Shoulda Been You) make fantastic use of Eugene Lee’s (Wicked) rustic set, an open cabin (reminiscent of the one at the start of The Jerk) where four members of the band (Michael Pearce, Bennett Sullivan, Rob Berman, Martha McConnell) play and which gets moved around as the setting changes to the offices of the Asheville Southern Journal, Margo’s bookstore, Mayor Dobbs’s residence, and the Shiny Penny bar. Occasionally a model train passes overhead when a character is traveling. Cusack is sensational in her Broadway debut, going back and forth between the young Alice to the older Miss Murphy with wit and elegance, singing with a vibrant, evocative voice and infectious confidence. The show works best when the music follows more of an Americana roots and bluegrass style, which is especially embraced by Nolan (Jesus Christ Superstar, Doctor Zhivago); his duets with Cusack are the musical highlights of the production. The weak link is the dull subplot about Billy’s desire to be a writer, with Shively (La Cage aux Folles, February House) too straitlaced to keep things interesting, lacking any edge, and Martin can get a little too erudite with his literary barbs. In addition to the musicians in the cabin, there are more up top on either side of the stage; Peter Asher’s music direction and August Eriksmoen’s orchestrations mostly work, although the Shiny Penny scene, featuring the ensemble song “Another Round,” is a disaster in every which way. (And why did they have to use glasses with tops on them, making it look ridiculous when characters apparently take a big drink but the same amount of liquid is still clearly visible in their glass?) Stephen Lee Anderson (The Iceman Cometh, The Kentucky Cycle) does a fine turn as Alice’s Bible-thumping father, and Mulheren (Spider-Man, Kiss Me, Kate) gives the mayor a Big Daddy–like presence. “Should’ve raised you with a firmer hand,” Daddy Murphy sings to his daughter in a strong number. For a show partially about writing, Bright Star would have benefited by being edited with a firmer hand, but it’s still an entertaining musical with supreme moments.

(On April 12, Martin and Brickell will be at the Upper West Side Barnes & Noble at 86th St. & Lexington Ave. for a discussion with Asher and a CD signing of So Familiar; priority seating will be given to attendees who purchase the disc there.)