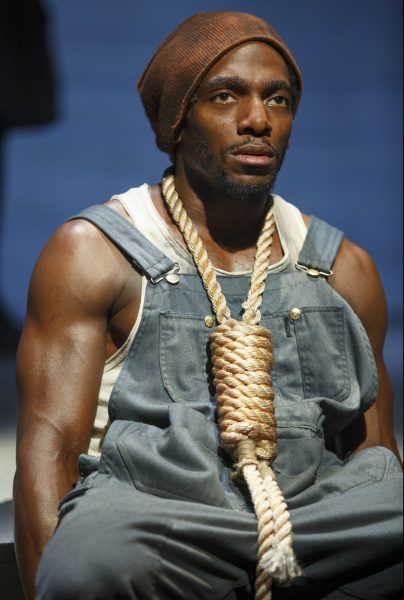

La Marquise de Merteuil (Janet McTeer) and Le Vicomte de Valmont (Liev Schreiber) use seduction as a weapon in Broadway revival of Christopher Hampton’s LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES (photo © Joan Marcus 2016)

Booth Theatre

222 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through January 22, $40- $159

liaisonsbroadway.com

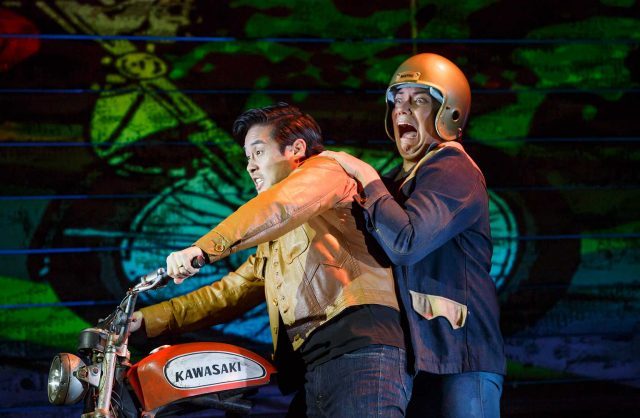

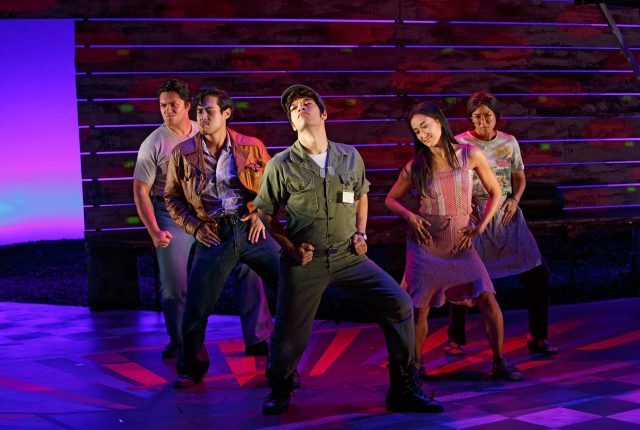

Tony winners Janet McTeer and Liev Schreiber take a somewhat unexpectedly playful tack in Josie Rourke’s Donmar Warehouse production of Christopher Hampton’s 1985 devilishly wicked Olivier Award winner, Les Liaisons Dangereuses, running at the Booth Theatre through January 22. In early 1780s Paris, former lovers La Marquise de Merteuil (McTeer) and Le Vicomte de Valmont (Schreiber) spend their days and nights calculating who they can sleep with, turning the art of seduction into a malicious game in which they manipulate and humiliate friends, enemies, strangers, and acquaintances primarily for the mere sport, although they occasionally have other goals. “Love and revenge: two of your favourites,” Merteuil tells Valmont. When Merteuil expresses her dissatisfaction with Valmont’s decision to attempt to bed the married, eminently proper Madame de Tourvel (Birgitte Hjort Sørensen) instead of the virginal fifteen-year-old Cécile Volanges (Elena Kampouris), daughter of Madame de Volanges (Ora Jones), who has spread talk of his bad-boy reputation, he explains, “I can’t agree with your theory about pleasure. You see, I have no intention of breaking down [Madame de Tourvel’s] prejudices. I want her to believe in God and virtue and the sanctity of marriage, and still not be able to stop herself. I want passion, in other words. Not the kind we’re used to, which is as cold as it’s superficial. I don’t get much pleasure out of that anymore. No. I want the excitement of watching her betray everything that’s most important to her. Surely you understand that. I thought ‘betrayal’ was your favourite word.” Accusing him of developing real feelings for Madame de Tourvel, Merteuil claims, “Love is something you use, not something you fall into, like quicksand, don’t you remember? It’s like medicine; you use it as a lubricant to nature.” Other sexual innuendos include such phrases as “I know Belleroche was pretty limp,” “I want you to help me stiffen his resolve,” “The position in which I find myself,” “Nothing firm,” and “I’m sure she’ll soon be back in the saddle.” Determined to bed Madame de Tourvel, Valmont heads out to the summer cottage of his elderly aunt, Madame de Rosemonde (Mary Beth Peil), where Madame de Tourvel is staying while her husband is off at war. In the meantime, Merteuil decides to go after young Cécile’s love, Le Chevalier Danceny (Raffi Barsoumian), as her next sexual toy.

The married Madame de Tourvel (Birgitte Hjort Sørensen) does not want to give in to the Le Vicomte de Valmont’s (Liev Schreiber) wicked charms in LES LIAISONS DANGEREUSES (photo © Joan Marcus 2016)

Based on Pierre Choderlos de Laclos’s 1782 epistolary novel about sexual manipulation, humiliation, and seduction in pre-revolutionary France, Les Liaisons Dangereuses has been adapted into numerous stage and screen versions as well as radio dramas, ballets, and operas; among the duos who have portrayed Merteuil and Valmont (or their equivalents) onstage and -screen are Lindsay Duncan and Alan Rickman, Jeanne Moreau and Gérard Philipe, Glenn Close and John Malkovich, Sarah Michelle Gellar and Ryan Phillippe, Catherine Deneuve and Rupert Everett, Duncan and Ciarán Hinds, and Annette Bening and Colin Firth. McTeer (Mary Stuart, A Doll’s House) and Schreiber (A View from the Bridge, Glengarry Glen Ross) are not quite electrifying in their roles, sometimes seeming more like brother and sister — if siblinghood makes one think of Cersei and Jaime Lannister from Game of Thrones. Valmont’s seduction of Cécile turns ugly fast, and his wooing of Madame de Tourvel has echoes of Richard III, but without the explicit evil. Tom Scutt’s costumes are rich and elegant but his set, a dilapidated living room with paintings (some wrapped partially with plastic, which would not be invented for another 125 years) lying on the floor against the walls, is rather mystifying; perhaps it represents the coming fall of the aristocracy in France, or maybe it is meant to evoke Merteuil’s and Valmont’s damaged states of mind. But Mark Henderson’s lighting is splendid, from circles of candles to chandeliers lowered from above. Rourke (Privacy, The Machine) has delivered a pleasurable period drama, if one that is not quite as illicitly rousing and arousing as it could have been.