A group of close-knit twentysomethings seek love and happiness in SIGNIFICANT OTHER (photo by Joan Marcus)

Booth Theatre

222 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through April 23, $49-$147

www.significantotherbroadway.com

In 2012, Joshua Harmon’s terrific Bad Jews debuted at the Roundabout’s tiny subterranean Black Box Theatre; the following year it moved upstairs to the much bigger Laura Pels, where it continued to play to sold-out houses. In 2015, Harmon’s equally terrific Significant Other debuted at the Laura Pels, and now it’s moved west to Broadway’s Booth Theatre, where it continues to attract well-deserved accolades. Significant Other is the sassy, heart-wrenching story of twenty-seven-year-old Jordan Berman (Gideon Glick), who becomes more and more depressed as his three best friends, Kiki (Sas Goldberg), Vanessa (Rebecca Naomi Jones, replacing Cara Patterson from the original production), and Laura (Lindsay Mendez), one by one find their significant other while he remains solo, terrified that he will never find his Mr. Right. He’s also afraid of maturity in general. “I wish we still lived together,” he says to Laura. “Grown-ups live alone,” she responds, to which he replies, “We’re grown-ups. I keep forgetting that.” He turns to his grandmother Helen (Barbara Barrie) for advice, but her memory is starting to slip and she occasionally discusses ways to kill herself. “I know life is supposed to be this great mystery, but I actually think it’s pretty simple: Find someone to go through it with. That’s it. That’s the, whatever, the secret,” Jordan says to Laura. “You make it sound so easy,” she says, to which he replies, “No, that’s the hardest part. Walking around knowing what the point is, but not being able to live it, and not knowing how to get it, or if I ever even will.” Jordan gets a sudden burst of energy when he suspects dreamy new coworker Will (John Behlmann) might be gay, but that only amplifies his deep-seated fears and worries.

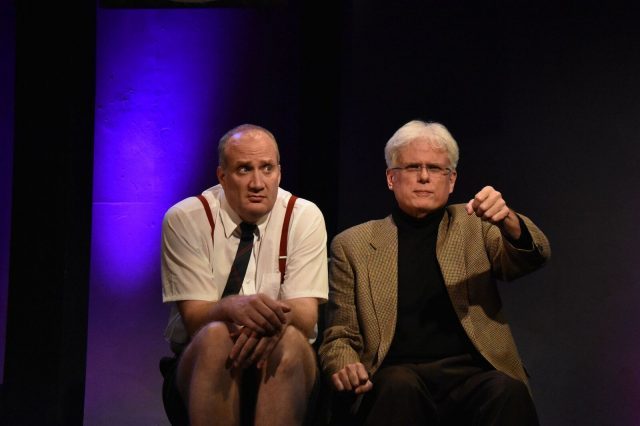

Grandma Helen offers Jordan (Gideon Glick) some relationship advice in SIGNIFICANT OTHER (photo by Joan Marcus)

Seeing Significant Other for the second time was like reconnecting with old friends. The main characters are beautifully drawn by Harmon and exuberantly brought to life by the cast, with Behlmann and Luke Smith playing all of the potential significant others. Director Trip Cullman (Yen, A Small Fire) hasn’t missed a beat with the transition to Broadway, retaining the play’s intimate charm; in fact, some scenes work even better, particularly those in which Jordan dances with Laura at several weddings. Mark Wendland’s vertical set features more than half a dozen inside and outside spaces, lit with pinpoint precision by Japhy Weideman; the lighting in the scene in which Jordan delivers a detailed monologue about seeing Will in a bathing suit is breathtaking and funny. All of the elements come together, but at the heart of everything is Glick’s (Spring Awakening, The Few) heartbreaking performance, which had me more teary-eyed the second time around. The scene in which he decides whether to send an email to Will is an out-and-out riot, while a later argument with one of his best friends is a spellbinding tour de force of writing, acting, and directing. Significant Other is the second of three Roundabout commissions for Harmon; we can’t wait to see what he comes up with next.