Ed Schmidt’s Edward is an intimate and poetic tale of an ordinary man’s life (photo courtesy Ed Schmidt)

EDWARD

All Street Gallery

119 Hester St. between Forsyth & Eldridge Sts.

Through May 18

edschmidttheater.com

allstnyc.com

Ed Schmidt knows about endings. His 2010 solo show, My Last Play, was ostensibly his swan song, written two years after the death of his father and a transformative rereading of Our Town, concluding a twenty-year career that had also featured Mr. Rickey Calls a Meeting, The Last Supper, held in his Brooklyn kitchen, and the monthly variety show Dumbolio. Nevertheless, in 2015, Schmidt, at the time a professor and basketball coach at Trinity on the Upper West Side, wrote and performed the high school basketball drama Our Last Game, staged in an actual high school locker room.

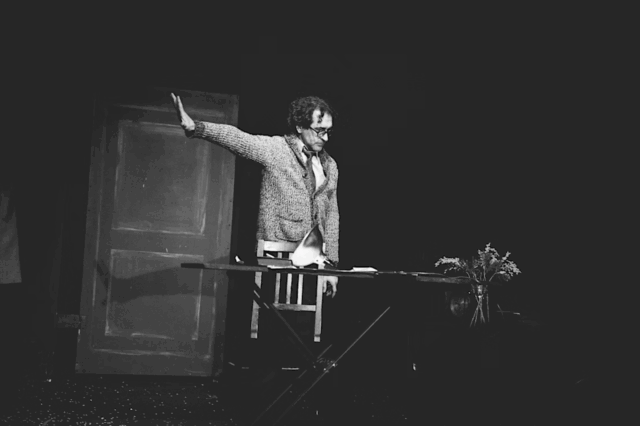

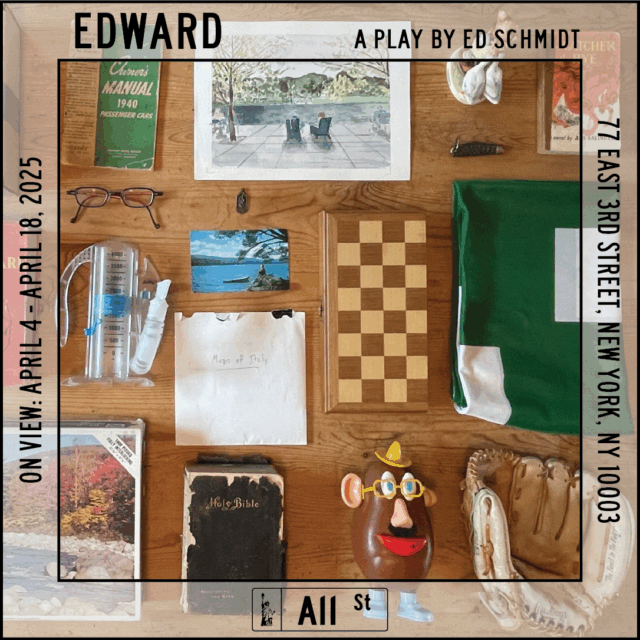

Thankfully, Schmidt is back again with the superb Edward, the poetic, graceful, intimate tale of one Edward O’Connell, an unspectacular but respectable and enigmatic divorced father and educator. The hundred-minute play takes place at All Street Gallery on Hester St., with the audience of between twelve and eighteen people sitting around a long white table covered with twenty-seven objects and an empty box. Fortunate ticket holders are encouraged to arrive early and examine each piece, to pick them up and scrutinize them closely: A Brooks Robinson baseball glove. Four neckties. Mr. Potato Head. A copy of The Catcher in the Rye. A “Goose Girl” Hummel. An ashtray. A jazz CD. A postcard of a boy on a lake. A business card.

“Edward O’Connell died twelve years ago, at the age of seventy-three, and left behind this box, and all that it contained,” Schmidt, resembling a mild-mannered Kevin Costner and sounding like a toned-down Albert Brooks, begins. “With these twenty-seven objects, there are over ten octillion ways to tell Edward’s story. Ten octillion. That’s a one followed by twenty-eight zeroes. That’s the number of grains of sand on the Earth. Multiplied by the number of stars in the Milky Way. In other words, an unfathomable number. Tonight, we will tell one of those ten octillion versions.”

Wearing a dark suit and white shirt, Schmidt then serves as an Our Town–style Stage Manager, going through the objects in random order, each one a way into Edward’s life, directly or indirectly. He speaks in the third person although it feels like he’s channeling O’Connell, delving deep into his being. We learn about Edward’s wife, Angela, and their children and grandchildren; his love of the Celtics and Red Sox; his battles with department head Nona and headmaster Renée Marsh at his school, Enright Academy; his first car; his favorite word; the vacation when he thought his son had drowned; where he was at seminal moments in US history; his multiple regrets.

Many passages unfurl with a quiet majesty. “He likened her transformation to watching a sunset: you can sense a change coming — the air cools, the light fades, the sky pinkens, and then, all of a sudden, you realize, ‘It’s dark. When did that happen?’ Or perhaps the proper metaphor was a sunrise, and darkness slowly, suddenly turning to day,” he muses.

Others are experiences that everyone can relate to. “You know how, on every To Do List, there’s that one task that never gets done? It’s the one item that, for whatever mysterious reason, you can’t cross off, and it ends up getting transferred to the next list and the next and the next, and, in the end, you either complete the task or you just let it slip away and forget, but, in either case, your inability to follow through feels like a moral failure. Why did it take me so long to clean out the gutters? Or send that thank-you note? Or throw away that box of stuff in the attic? What is wrong with me?”

But each helps us learn who Edward O’Connell was and, in turn, who Ed Schmidt is — and who we are. As you walk around the table, examining the objects, several almost certainly will stand out to you personally, bringing up your own memories; for me, the baseball glove, The Catcher in the Rye, the small rock, and the Hummel figurine sent me back. The friend I attended with had actually completed the very jigsaw puzzle that was on the table. Schmidt’s writing is so evocative that the stories will also remind you of similar situations you got tangled up in as a child and an adult.

In Francesco Bonami’s newly updated semifictional Stuck: Maurizio Cattelan — The Unauthorized Autobiography, about the Italian artist and prankster, Bonami writes, “Here is my story of his story. You can believe it or not — it doesn’t matter, just as long as you enjoy it, that’s enough. If cultivating ‘doubt’ is essential to life . . . well, Maurizio Cattelan harvests doubts like nobody else.” Schmidt has accomplished a similar feat with Edward.

Spoiler alert: The next two paragraphs give information about the show that you might not want to know before seeing it but was a critical part of my connecting with the work. The objects are chosen one at a time by the audience, going around in a clockwise circle. I thought long and hard about the two that I selected, wanting to impress Schmidt, hoping they would lead to great anecdotes that I would feel partly responsible for, and imagining that I could have shared my own reminiscence about them.

It seems impossible for Schmidt to know O’Connell as well as he does, especially since Edward did not leave behind a memoir or journal. But as real as O’Connell’s life appears to be, did he even exist? Did Schmidt make it all up, or perhaps use elements from his own life in crafting the play? Going on an intense Google search, I found that there is very little on the internet about Schmidt, and there seems to be no Edward O’Connell who died in 2012 at the age of seventy-three. However, I did find facts about other Edward O’Connells and various Schmidts that pop up in Edward, from names to professions to family relationships. For example, Schmidt talks about a skiing accident that Edward’s brother, Steven, had. I discovered a Substack post by political pundit Steve Schmidt about a skiing accident as well as a news story about a man named Steve Schmit who survived a life-threatening skiing mishap. Coincidence? Maybe — but maybe not.

Spoilers over, it’s also clear that Schmidt has some prankster in him too, as well as a wicked sense of humor, which emerges in his official bio, where he calls himself a “Playwright, Performer, Director, Producer, Genius,” lists the many rejections his plays have received from “some of the most and least venerable theater companies in America,” and explains that “none of Mr. Schmidt’s work has been made possible, in part or in whole, by the generous support of the National Endowment for the Arts, the New York State Council on the Arts, or the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs, or of any corporate foundation or charitable institution, though it’s not for lack of trying.”

As Bonami posits about Cattelan, “It doesn’t matter, just as long as you enjoy it, that’s enough.” For one thoroughly enjoyable evening in a Lower East Side gallery, it was enough to believe in Edward O’Connell, to believe in Ed Schmidt, and just maybe to believe in oneself.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]