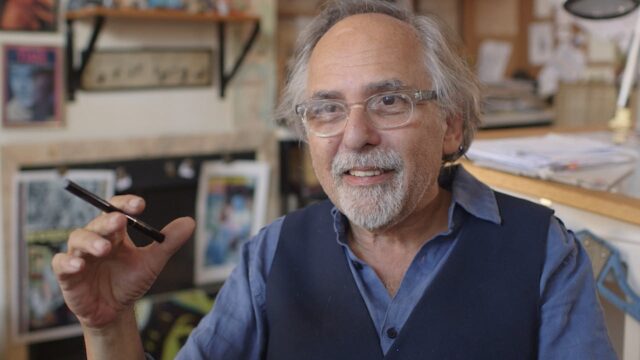

Art Spiegelman discusses hie life and career in Disaster Is My Muse

COMIC ARTS FEST 2025: ART SPIEGELMAN: DISASTER IS MY MUSE (Molly Bernstein & Philip Dolin, 2024)

L’Alliance New York, Florence Gould Theater, Tinker Auditorium

55 East 59th St. between Madison & Park Aves.

Friday, March 28, $30.55 – $54.20, 7:30

Festival runs March 28–30, pass $86.10

212-355-6100

lallianceny.org

In the documentary Art Spiegelman: Disaster Is My Muse, Pulitzer Prize–winning cartoonist and editor Art Spiegelman explains, “I did take comics very, very seriously, and I thought they were time turned into space, a perfect container for memory, and an incredibly maligned art form. And without being pretentious about it, I thought that this was as valid as anything that happened in literature or in painting, or in cinema.”

Winner of the 2024 DOC NYC Grand Jury Prize in the Metropolis Competition, the hundred-minute PBS American Masters film is part of the opening-night celebration of the 2025 Comic Arts Fest, taking place March 28–30 at L’Alliance New York; it will be shown on Friday evening at 7:30, followed by a Q&A with special guests and a party with food and drink, music, and a live Exquisite Corpse session with guest illustrators.

In the documentary, Bernstein and Dolin incorporate archival footage, family photos, detailed investigations of key panels from many of Spiegelman’s comics and graphic novels, and new interviews with such comic artists as Griffith, R. Crumb, Trina Robbins, Gary Panter, Charles Burns, Chris Ware, Peter Kuper, and Jerry Craft in addition to author Hillary Chute, film critic J. Hoberman, filmmaker Ken Jacobs, Spiegelman, Mouly, and their children, Dash and Nadja. “By showing in your comics stuff you’re not supposed to show, stuff you’re not supposed to deal with, the culture outside is telling you don’t go there, by doing it, you’re robbing it of its power,” Griffith says of his Arcade cofounder’s aesthetic.

Mouly offers, “Art has never separated work and life,” especially when it comes to his genre-redefining 1986 graphic novel, Maus: A Survivor’s Tale (My Father Bleeds History) and the 1991 sequel, Maus: And Here My Troubles Began. The books explore his complicated relationship with his Polish father, Vladek, who finally told his son about his experiences at Auschwitz, a subject that he and Art’s mother, Anna, had previously avoided delving into with him.

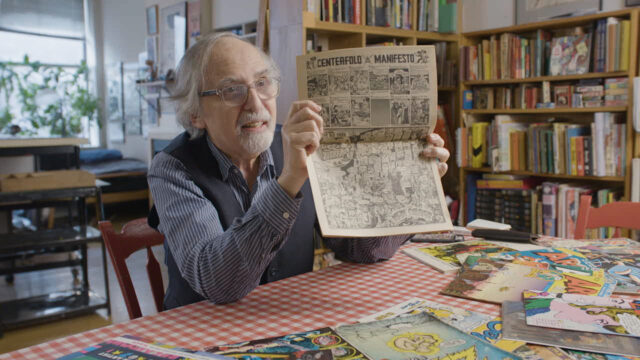

Art Spiegelman holds up the 1973 “Centerfold Manifesto” in poignant documentary

In the books — which the New York Times originally listed as fiction until Spiegelman wrote them a letter explaining that Maus was a carefully and thoroughly researched true story and should be categorized as nonfiction — Spiegelman depicted the Jews as mice and the Nazi soldiers as evil cats. “He tackled a subject that was enormous and he established the medium as a serious literary form,” Sacco says.

As deeply personal as Maus is — the documentary includes scenes of Spiegelman visiting Auschwitz in 1987 — it is primarily a human tale of innocent people trapped amid the scourge of Fascism, something Spiegelman has been warning people about given what is happening around the world this century.

“Art Spiegelman is the guy that reinvented comics as a medium that people took seriously,” artist and author Molly Crabapple says. “He showed that comics could express the darkest, most tragic, most complicated, most true things about history, about our relationships, about family.” Disaster Is My Muse was made prior to Donald Trump reclaiming the presidency in November, but Spiegelman makes his feelings about him very clear in lectures and conversations.

Speaking about his early, radical work with EC and Mad writer and editor Harvey Kurtzman, Spiegelman notes, “It was asking you to deeply question things, and I believe it was an important aspect of what led to the generation that protested the Vietnam War.” Among the other topics that are examined are several of Spiegelman’s autobiographical panels from Breakdowns: Portrait of the Artist as a Young %@&*!; 1968’s Prisoner on the Hell Planet: A Case History, about his mother’s suicide, the comic that first attracted Mouly to him; his longtime association with Topps designing Wacky Packages and Garbage Pail Kids cards; making potent New Yorker covers; his 9/11 book, In the Shadow of No Towers; Maus being banned in many school libraries across the country; such influences as Mad magazine #11 and Bernard Krigstein’s Master Race; his adaptation of Joseph Moncure March’s 1928 lost classic, The Wild Party; and his time spent in a state mental facility and the tragic death of his brother. Although his smoking habit is never mentioned, he is nearly always seen with a pipe, cigarette, or vape.

In 1973, Spiegelman and Griffith created the “Centerfold Manifesto” in Short Order Comix #1, which proclaimed, “Comics must be personal! . . . Efficient and Callous Capitalist Exploitation must be condemned and deplored at every turn . . . And replaced by Inefficient and humane Capitalist Exploitation!” More than fifty years later, he is still living by his word.

The Comic Arts Fest overflows with opportunities to appreciate the art form Spiegelman champions: Highlights include screenings of four episodes from season two of Florian Ferrier’s series The Fox-Badger Family and four episodes of Daniel Klein’s Living with Dad, the masterclass “Aleksi Briclot: My Journey with Marvel Studios,” the conversation “The Return of the Iconic Gaston Lagaffe” with Delaf, the lecture “The Rise of Afromanga” with Gigi Murakami, a screening of Anora Oscar winner Jacques Audiard’s Paris, 13th District followed by a discussion with artist Adrian Tomine, a screening of Silenn Thomas’s Frank Miller: American Genius followed by a Q&A with Thomas and artist Emma Kubert, and the closing event, “Françoise Mouly, from Indie Comics to the New Yorker,” in which Spiegelman’s wife and business partner sits down with Anita Kunz, Peter de Sève, Barry Blitt, and others to talk about her career. Spiegelman will also be at the Artist Alley & Bookstore section of the fest on March 30 from 3:30 to 5:30; among the other participants are Paul & Gaëtan Brizzi, Patrick McDonnell, Pauline Lévêque, Griffith, and Tomine.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]