Danielle Ryan and Stephen Brennan are exceptional as a bitter daughter and father in streaming revival of Marina Carr’s The Cordelia Dream

THE CORDELIA DREAM

Irish Rep Online

Daily through August 8, suggested donation $25

irishrep.org

Summer theater in New York City is dominated by outdoor Shakespeare presentations, including Shakespeare in the Parking Lot’s Two Noble Kinsmen, the Classical Theatre of Harlem’s Seize the King, the Public Theater’s Merry Wives of Windsor at the Delacorte and the Mobile Unit’s Shakespeare: Call and Response, and NY Classical’s King Lear with a happy ending.

One of the best productions is taking place indoors, but not in a theater with an audience. I wouldn’t be giving anything away if I told you that there is no happy ending in the Irish Rep’s virtual revival of Marina Carr’s The Cordelia Dream, streaming online through August 8. The brutal, relentless two-act, ninety-minute play was commissioned by the Royal Shakespeare Company and debuted in 2008 at Wilton’s Music Hall in London. Charlotte Moore and Ciarán O’Reilly of the Irish Rep, in association with casting director and producer Bonnie Timmermann, enlisted director Joe O’Byrne to helm a new version filmed at the New Theatre in Dublin, as part of the innovative company’s continuing onscreen works made during the pandemic.

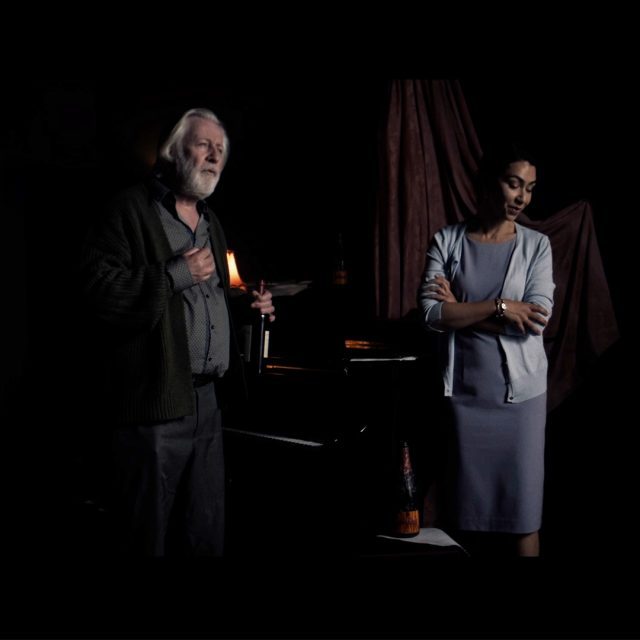

The play takes place in a dark, eerie room where an elderly man (Stephen Brennan) lives alone, drinking by himself and playing his piano. He is visited one day by his long-estranged daughter (Danielle Ryan); they have not seen each other in many years, and their discomfort and hostility are immediately apparent in their initial exchange.

Man: You.

Woman: Yes. Me.

Man: Well.

Woman: It wasn’t easy . . . seeking you out.

Man: Wasn’t it?

Woman: I stayed away as long as I could.

Man: You think I’m going to die soon?

Woman: Maybe.

Man: You want to kiss and make up before the event?

Woman: Some people visit each other all the time.

Man: I’m not some people. You of all people should know that.

Woman: Can I come in or not?

There is no love lost between father and daughter; it’s as if an older Cordelia has come to see her aging father, both filled with resentment, no reconciliation in sight. “Love needs a streak of darkness. The day is for solitude. Morning especially. Morning is for death,” he says. “And afternoons?” she asks. “At your age they’re for transgressions, at mine they’re for remorse,” he replies. “You know about remorse?” she wonders. “I’m an expert on it,” he answers.

Both characters are revealed as cold and cruel as details of their lives emerge in the corrosive conversation. He is an extremely talented but failed composer attempting to create his magnum opus before he dies, while she is a famous composer who has not been able to enjoy her success. He accuses her of wasting her gifts, claiming his superiority, unashamed of his hatred of her. He is glad that none of her children are named after him; he even criticizes the wine she brought. “You are very mediocre,” he declares. “Does mediocre need ‘very’ in front of it?” she asks. “When talking about you. Yes, it does,” he replies with bitterness.

She is there to say her piece, not about to cower from him. “You haven’t left me alone,” she says. “You’ve retreated to this sulphurous corner to gather venom for the next assault. You? Leave me alone? You haunt me.”

She has also come to tell him about a dream she has had, about their life and death, about the four howls and the five “never”s in Shakespeare’s grand tragedy. “You think you’re Cordelia to my Lear. No, my dear. You’re more Regan and Goneril spun,” he spits at her. “And you’re no Lear,” she shoots back, soon leaving.

She returns five years later, but it is not quite the same. His mental faculties are decreasing, not unlike the mad Lear’s, thinking her to be the goat-faced, dog-hearted dark lady of his nightmares, a reference to the character Shakespeare addresses in Sonnet 130 and others, whom he loves but cannot outright compliment, disparaging her instead. He recalls moments from his past but is foggy. “Your self-delusion is complete,” she says. “Men should not have daughters,” he opines. The acerbic cat-and-mouse dialogue continues as they eviscerate each other till nothing’s left.

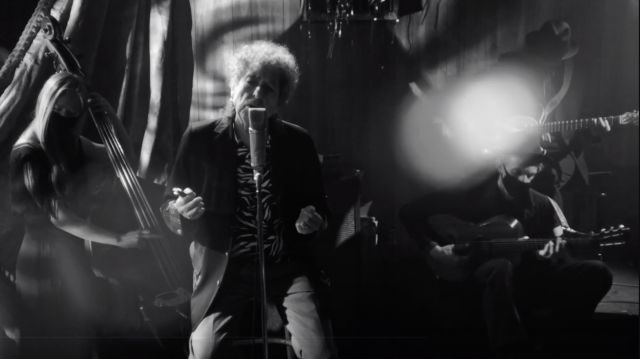

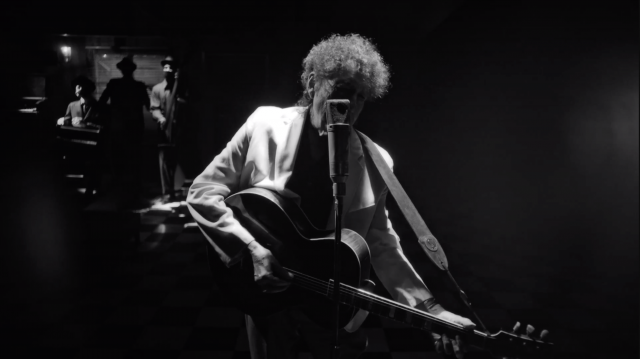

Fiercely directed by Joe O’Byrne (McKeague and O’Brien present “The Rising,” Frank Pig Says Hello), The Cordelia Dream is a merciless, unyielding depiction of an unredeemable relationship between a father and daughter. With biting language, Carr (Woman and Scarecrow, Marble) brilliantly compares the creation of a work of art to the birth of a child and all the responsibilities that are supposed to accompany it. The play is intimately photographed and edited by Emmy winner Nick Ryan, with ghostly set design by Robert Ballagh and sound and original music by Emmy nominee David Downes, the actors naturally lit by a few lamps and a window that offers brief reprieves from the enveloping darkness that makes it feel like it is all a dream.

Brennan (A Life, The Pinter Landscape) commands the screen with an immense presence, his white-haired, white-bearded character skewering his daughter with relish, unafraid of any consequences. Ryan (Harry Wild, Wild Mountain Thyme), who made her professional debut in 2007 playing Cordelia and Brigitte in the Edinburgh Fringe award winner Food, portrays the lost woman with a graceful finesse as she tries to unburden herself of the many ways she claims he destroyed her life. The harrowing work hits even deeper at a time when loved ones are reuniting after the long pandemic lockdown, with hugs and kisses, smiles of relief and unabashed joy, none of which is evident in these two characters who harbor a disturbing, apparently unsalvageable history.