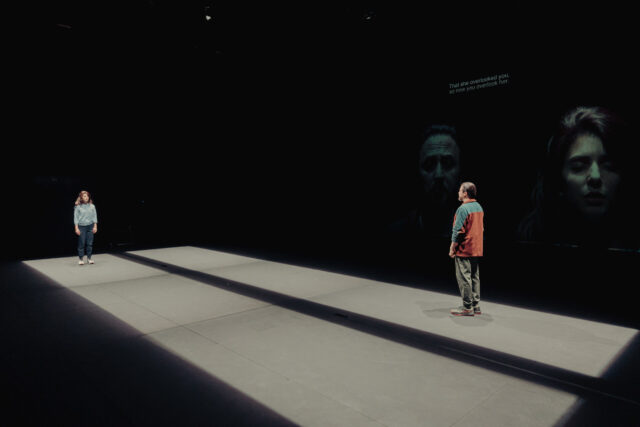

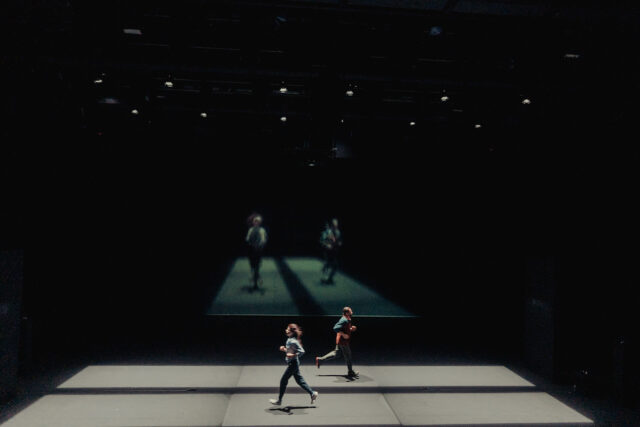

Christina Phensy’s Elegy for the Future is part of opening night of Marvels of Media Festival at MoMI

MARVELS OF MEDIA FESTIVAL 2025

Museum of the Moving Image

35th Ave. at 36th St., Astoria

March 27-29, free with advance RSVP

movingimage.us

The Marvels of Media Festival returns to the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI) for its fourth iteration, celebrating the work of autistic creators with film screenings, panel discussions, workshops, an exhibition, and satellite locations in Westchester, Long Island, and San Francisco.

“Marvels of Media has shown the brilliant work of neurodiverse media makers in clear evidence,” MoMI trustee and founder of Marvels of Media and Sapan Studio Josh Sapan said in a statement. Debut filmmaker and As We See It star Sue Ann Pien added, “Expanding the audience’s understanding of an autistic female’s reality is a perspective changer for those more accustomed to stereotypically male depictions in film and television history. It’s a culturally relevant reminder that no one person is meant to represent an entire spectrum (just like not everyone with blue eyes or brown hair is the same).”

The three-day festival features twenty-two films, five video games, and two virtual reality experiences focusing on the neurodivergent community. The opening-night selection is the East Coast premiere of Pien’s fifteen-minute short, Once More, Like Rain Man, which she explains “gives a voice to a young autistic teenage girl’s own experiences finding her creative empowerment through the casting process.” Also on the bill is Christina Phensy’s fourteen-minute Elegy for the Future; Pien appears in both works. The evening also includes a panel discussion on autistic representation, with Pien, actress Bella Zoe Martinez, and Phensy, moderated by filmmaker and playwright Jackson Tucker-Meyer, and will be followed by a reception and a viewing of the exhibition “The Adventure of Nature and the Senses,” consisting of five films totaling fifteen minutes and the VR presentations Booper, Get Home by Thomas Fletcher and MUD & TKU Student Work XR/VR Gallery by Mike S., Opy S., Pattrick L., Rafat A., Tate B., Xavier A., Rose L., Briana G., Sasha R., Alejan T., Joshua K., and Koby F. In addition, the Marvels of Media Game Lab Exhibition includes Elliot Rex White’s visual novel A Night for Flesh and Roses as well as Metal Place by Abdullah Kante, Fizzy Adventure by Alex Lundqvist, Awesome Game by Carter Lee, and The Happy Hedgehog Wants a Big Wish by Tech Kids Unlimited’s Digital Agency.

We’ve come a long way since Rain Man.

Below is the full schedule.

Thursday, March 27

“Vibrant Voices: Four Shorts”: House of Masks by Atticus Jackson and Jason Weissbrod, 420 Ways to Die by Samara Huckvale, Insight by Ben Stansbery, and Breaking Normal by Jessica Cabot, followed by a discussion with Weissbrod, Huckvale, Stansbery, and Tal Anderson, 4:00

“Marvels of Media Festival Opening Night,” with opening remarks from Josh Sapan, Aziz Isham, Leonardo Santana-Zubieta, and Miranda Lee; screenings of Once More, Like Rain Man by Sue Ann Pien and Elegy for the Future by Christina Phensy; panel discussion, reception, and exhibition viewing (including Night City by Kyle Davis, Daltokki by Daniel Oliver Lee, CMYK Walk in the Woods by Quinn Koeneman, As One by Bec Miriam, and Jellyfish Memories by Eliza Young), 6:30

Friday, March 28

New York premiere of Lone Wolves (Ryan Cunningham, 2024), followed by discussion with Cunningham (in person) and writer-actor Matt Foss (via live video), 6:00

Saturday, March 29

“Playful Tales: Six Shorts”: Secret of the Hunter by Jessica “Jess” Jerome, Wilson S. Whale by Harry Schad, Abelard the Traveling Hedgehog’s Underwater Adventure with Max the Turtle by Pete Peterman and Ambrose Peterman, Joust My Luck by Jacob Lenard, The Ugliest Masterpiece by Rae Xiang, and Julius’ Identity Crisis by Brendan Ratner, followed by a discussion with Schad, Lenard, Xiang, Ratner, Payton Hepler, and Andy Nava, moderated by Mr. Oscar Segal and Allison Tearney, 1:00

“Life Lessons: Four Shorts”: Unbreakable by Alex Astrella, Glitter by Violet Gallo and Maya Velazquez, Surviving the Spectrum by Carley Marissa Dummitt, and Late-Diagnosed by Matthew Baltar, followed by a discussion with Gallo, Baltar, and Dummitt, 2:30

“Media-Maker Talk and Networking Mixer,” with Jason Weissbrod and others, 6:00

Sunday, March 30

“Collage Animation Workshop,” with artist David Karasow, 4:00

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]