Photographer unknown, Harry Smith at Naropa Institute, gelatin silver print, 1990 (Harry Smith Papers, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles; gift of the Harry Smith Archives)

MY HARRY

Whitney Museum of American Art, Education Center and Hess Family Theater

99 Gansevoort St.

December 8-10, $18-$25

212-570-3600

whitney.org

The Whitney celebrates the legacy of American polymath Harry Smith in the three-day festival “My Harry.” Held in conjunction with the multimedia exhibition “Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: The Art of Harry Smith,” which continues at the museum through January 28, the revelry features listening sessions, illustrated lectures, film screenings, conversations, live music, art workshops, and more, with appearances by friends and colleagues of Smith, who was born in Portland, Oregon, in 1923 and died in New York City in 1991 at the age of sixty-eight, leaving behind a treasure trove of music, art, and film that he both made and collected, as well as a lifelong interest in the occult. Among those participating in the weekend are Carol Bove, Ali Dineen, Bradley Eros, Raymond Foye, Andrew Lampert, April and Lance Ledbetter, James Inoli Murphy, Rani Singh, Peter Stampfel, Charles Stein, and Anne Waldman. Below is the full schedule.

My Harry: Magick and Mysticism

Friday, December 8, $8-$10, 5:30–9 pm

Listening Session: Harry Smith’s Field Recordings, 5:30

Fragments of a Faith Forgotten: A Presentation by Carol Bove, with Carol Bove and Andrew Lampert, 6:30

Screening of Harry Smith’s “Film No. 14: Late Superimpositions,” 7:30

Harry Smith and the Future of Magick: A Presentation by Charles Stein, with Charles Stein and Raymond Foye, 8:00

Harry Smith, Untitled [Zodiacal hexagram sctratchboard], ink on cardstock, ca 1952 (Lionel Ziprin Archive, New York)

My Harry: Stories, Songs, and Strings

Saturday, December 9, free with museum admission, 11:00 am – 6:00 pm

Stop Motion Animation Studio and Paper Airplane Workshop, hosted by Bradley Eros, 11:00 am – 3:00 pm

Singing Circle with Ali Dineen, 11:00 am

Peter Stampfel and the Atomic Meta-Pagan Posse, with Peter Stampfel, Eli Smith, Zoe Stampfel, Eli Hetko, Steve Espinola, Paul Nowinski, Sam Werbalowsky, Heather Wagner, and Dok Gregory, 12:00

String Figure Workshop with James Inoli Murphy, 12:00

Paper Airplane Contest with Bradley Eros, 2:00

On Mahagonny: A Presentation by Rani Singh, 5:00

My Harry: Affinities

Sunday, December 10, free with museum admission, 11:00 am – 5:00 pm

Listening Session: Harry Smith’s Field Recordings, 11:00 am

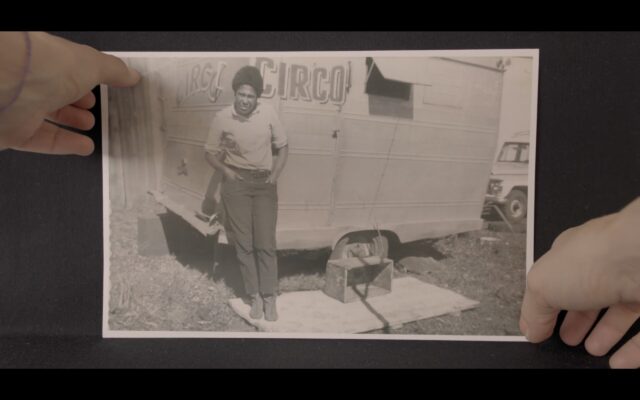

On Harry’s Trail: A Presentation by Dust-to-Digital, with Lance and April Ledbetter, 12:00

Screening: A selection of films and videos featuring Harry Smith by a variety of the artist’s friends and associates, 1:00

Friendly Rivals: The Art of Jordan Belson, a Presentation by Raymond Foye, 3:00

Anne Waldman, 4:00

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]