A sadistic teacher (Stig Järrel) torments a student (Alf Kjellin) in Ingmar Bergman–written Frenzy

FRENZY (TORMENT) (HETS) (Alf Sjöberg, 1944)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

Wednesday, February 7, 4:00 & 8:20; Tuesday, February 27, 6:30

Series runs February 7 – March 15

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

Film Forum is celebrating the centennial of Swedish master Ingmar Bergman’s birth with a five-week retrospective of nearly four dozen films he directed and/or wrote, forty of which are new restorations from the Swedish Film Institute. The series, running from February 7 through March 15, kicks off with one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, 1957’s The Seventh Seal, in which an errant knight played by Max von Sydow sits down for a game of chess with Death (Bengt Ekerot), as well as the intense 1944 expressionistic noir, Frenzy. Although directed by Alf Sjöberg, Frenzy, also known as Torment, was written by Bergman, who also served as assistant director and made his directing debut in the final scene, which Bergman added at the insistence of the producers when Sjöberg was not available. A kind of inversion of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, the film is set in a boarding school where high school boys are preparing for their final exams and graduation. They are terrified of their sadistic Latin teacher, whom they call Caligula (Stig Järrel), a brutal man who wields a fascistic iron fist. He particularly has it out for Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin), the son of wealthy parents (Olav Riégo and Märta Arbin) who think he should be doing better in school. One night Jan-Erik helps out a troubled woman in the street, tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling), who is being mentally and physically tormented by an unnamed man who ends up being Caligula. The stakes get higher and the teacher becomes even harder on Jan-Erik when he finds out the young man is having an affair with the wayward woman. When tragedy strikes, Jan-Erik’s soul is in turmoil as lies, threats, and danger grow.

Film Forum is celebrating the centennial of Swedish master Ingmar Bergman’s birth with a five-week retrospective of nearly four dozen films he directed and/or wrote, forty of which are new restorations from the Swedish Film Institute. The series, running from February 7 through March 15, kicks off with one of the greatest and most influential films ever made, 1957’s The Seventh Seal, in which an errant knight played by Max von Sydow sits down for a game of chess with Death (Bengt Ekerot), as well as the intense 1944 expressionistic noir, Frenzy. Although directed by Alf Sjöberg, Frenzy, also known as Torment, was written by Bergman, who also served as assistant director and made his directing debut in the final scene, which Bergman added at the insistence of the producers when Sjöberg was not available. A kind of inversion of Josef von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, the film is set in a boarding school where high school boys are preparing for their final exams and graduation. They are terrified of their sadistic Latin teacher, whom they call Caligula (Stig Järrel), a brutal man who wields a fascistic iron fist. He particularly has it out for Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin), the son of wealthy parents (Olav Riégo and Märta Arbin) who think he should be doing better in school. One night Jan-Erik helps out a troubled woman in the street, tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling), who is being mentally and physically tormented by an unnamed man who ends up being Caligula. The stakes get higher and the teacher becomes even harder on Jan-Erik when he finds out the young man is having an affair with the wayward woman. When tragedy strikes, Jan-Erik’s soul is in turmoil as lies, threats, and danger grow.

Tobacco-shop clerk Bertha Olsson (Mai Zetterling) is terrified of life in Alf Sjöberg’s Frenzy

The twenty-five-year-old Bergman was inspired to write his first produced film script by his experience in boarding school, which led to a public disagreement with the headmaster. In a public letter to the headmaster, Bergman explained, “I was a very lazy boy, and very scared because of my laziness, because I was involved with theater instead of school and because I hated having to be punctual, having to get up in the morning, do homework, sit still, having to carry maps, having break times, doing tests, taking oral examinations, or to put it plainly: I hated school as a principle, as a system and as an institution. And as such I have definitely not wanted to criticize my own school, but all schools.” Throughout his career, Bergman would take on institutions, including religion and marriage, but his defiance began with this hellish representation of education, which oppresses all the boys in some way, including Jan-Erik’s best friend, self-described misogynist Sandman (Stig Olin), and the geeky Pettersson (Jan Molander). While the headmaster (Olof Winnerstrand) knows how frightened the boys are of Caligula, he is willing to go only so far to protect them. The opening credits are shown over a dreamlike sequence of Jan-Erik and Bertha desperately holding on to each other, but Frenzy is so much more than a treacly melodrama, as if Sjöberg (Miss Julie, Ön) is setting us up for one film before switching gears into an ominous, haunting thriller.

Järrel, who played an evil, jealous teacher in his previous film, Hasse Ekman’s Flames in the Dark, is indeed scary as the devious, malicious Caligula, while adding more than a touch of sadness. Zetterling, in her breakthrough role — she would go on to star in such other films as Frieda and The Witches and direct such feminist works as Loving Couples and The Girls — brings a touching vulnerability to Bertha, a young woman who can’t find happiness. It’s all anchored by Kjellin’s (Madame Bovary, Ship of Fools) central performance, so rife with emotion it evokes German silent cinema. Frenzy suffers from Hilding Rosenberg’s overreaching score, although it is usually offset by Martin Bodin’s cinematography, filled with lurching shadows and deep mystery. The film was produced by Victor Sjöström, the legendary director of The Phantom Carriage, The Divine Woman, The Wind, and so many others in addition to his work as an actor, starring as Professor Isak Borg in another Bergman masterpiece, 1957’s Wild Strawberries, and as the conductor in 1950’s To Joy. (Film Forum is also presenting the five-film series “Victor Sjöström: The Screen’s First Master” February 11 through March 5, with live piano accompaniment at each show.) A Grand Prix winner at Cannes, Frenzy is screening February 7 and 27; among the many other highlights of Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective are Crisis, his full-length directorial debut; All These Women, his first color film, being shown with a detergent commercial he shot with Bibi Andersson; the 1969 and 1979 documentaries Fårö Document; and his last feature film, After the Rehearsal, and last short, Karin’s Face.

Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) sits down with Death (Bengt Ekerot) for a friendly game of chess in Bergman classic

THE SEVENTH SEAL (Ingmar Bergman, 1957)

Film Forum

February 7-10

filmforum.org

It’s almost impossible to watch Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal without being aware of the meta surrounding the film, which has influenced so many other works and been paid homage to and playfully mocked. Over the years, it has gained a reputation as a deep, philosophical paean to death. However, amid all the talk about emptiness, doomsday, the Black Plague, and the devil, The Seventh Seal is a very funny movie. In fourteenth-century Sweden, knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) is returning home from the Crusades with his trusty squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand). Block soon meets Death (Bengt Ekerot) and, to prolong his life, challenges him to a game of chess. While the on-again, off-again battle of wits continues, Death seeks alternate victims while Block meets a young family and a small troupe of actors putting on a show. Rape, infidelity, murder, and other forms of evil rise to the surface as Block proclaims “To believe is to suffer,” questioning God and faith, and Jöns opines that “love is the blackest plague of all.” (Bergman fans will get an extra treat out of the knight being offered some wild strawberries at one point.) Based on Bergman’s own play inspired by a painting of Death playing chess by Albertus Pictor (played in the film by Gunnar Olsson), The Seventh Seal, winner of a Special Jury Prize at Cannes, is one of the most entertaining films ever made, and you can bask in its glory February 7-10 when it screens in Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective.

It’s almost impossible to watch Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal without being aware of the meta surrounding the film, which has influenced so many other works and been paid homage to and playfully mocked. Over the years, it has gained a reputation as a deep, philosophical paean to death. However, amid all the talk about emptiness, doomsday, the Black Plague, and the devil, The Seventh Seal is a very funny movie. In fourteenth-century Sweden, knight Antonius Block (Max von Sydow) is returning home from the Crusades with his trusty squire, Jöns (Gunnar Björnstrand). Block soon meets Death (Bengt Ekerot) and, to prolong his life, challenges him to a game of chess. While the on-again, off-again battle of wits continues, Death seeks alternate victims while Block meets a young family and a small troupe of actors putting on a show. Rape, infidelity, murder, and other forms of evil rise to the surface as Block proclaims “To believe is to suffer,” questioning God and faith, and Jöns opines that “love is the blackest plague of all.” (Bergman fans will get an extra treat out of the knight being offered some wild strawberries at one point.) Based on Bergman’s own play inspired by a painting of Death playing chess by Albertus Pictor (played in the film by Gunnar Olsson), The Seventh Seal, winner of a Special Jury Prize at Cannes, is one of the most entertaining films ever made, and you can bask in its glory February 7-10 when it screens in Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective.

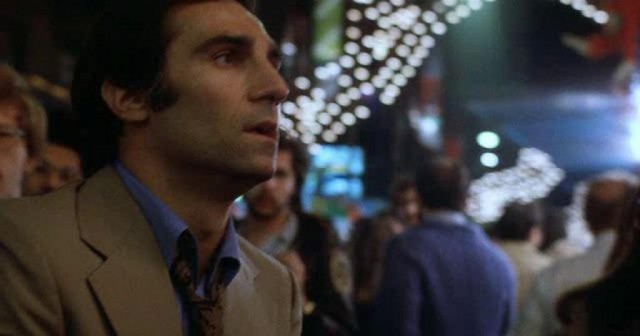

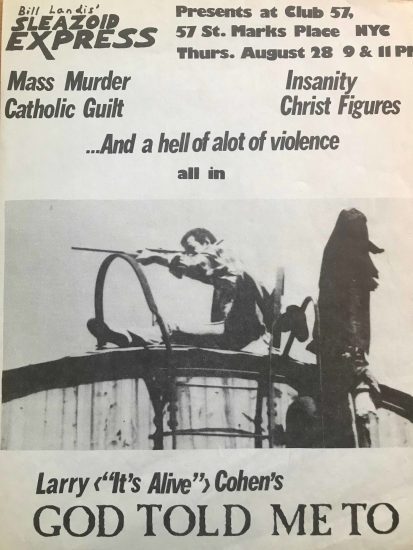

Watching the first half hour of Larry Cohen’s 1976 thriller, God Told Me To, is extremely difficult, given the continuing spate of mass shootings in the United States and the battle over gun control. The film opens with a man (Sammy Williams) on top of a water tower in New York City, picking off random people down below with a .22 caliber rifle. Detective Peter Nicholas (Tony Lo Bianco) risks his life to go face-to-face with the soft-spoken killer, who says he did it because “God told me to.” A religious Catholic suffering a crisis of faith, Nicholas gets the same response from a series of other mass murderers, including a cop played by Andy Kaufman, in his big screen debut, who lets loose during the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. (The next scene takes place at the Feast of San Gennaro, which is held every September in Little Italy, but it’s clear that six months have not elapsed, so we’ll give Cohen, a native of Washington Heights, poetic license in this case.) As Lo Bianco gets deeper and deeper into the mystery that involves an odd, cultlike figure named Bernard Phillips (Richard Lynch), he also has to deal with his estranged wife, Martha (Sandy Dennis), and his younger girlfriend, Casey Forster (Deborah Raffin). As he gets closer to the truth, he is forced to look deep into his soul amid all the madness. God Told Me To is shot by cinematographer Paul Glickman guerrilla style primarily without city permits and using a handheld camera, keeping the viewer off balance; the choppy editing by Michael D. Corey, Arthur Mandelberg, and William J. Waters doesn’t help smooth things out. The production values are quintessential low-budget mid-’70s, eliciting screams not of horror but of campy enjoyment among the middle-aged, who grew up watching these offbeat films at offbeat times in wood-paneled basements. Inspired by the Bible and one of the very first “aliens visited Earth!” books, Erich von Däniken’s bestselling Chariots of the Gods, Cohen, a producer, director, and writer who made such other low-budget faves as Black Caesar, It’s Alive, Q, The Stuff, and The Masters of Horror episode Pick Me Up, creates some intense scenes, including a hellish visit to a burning underground lair, as the twisting plot enters sci-fi territory involving a very special vagina.

Watching the first half hour of Larry Cohen’s 1976 thriller, God Told Me To, is extremely difficult, given the continuing spate of mass shootings in the United States and the battle over gun control. The film opens with a man (Sammy Williams) on top of a water tower in New York City, picking off random people down below with a .22 caliber rifle. Detective Peter Nicholas (Tony Lo Bianco) risks his life to go face-to-face with the soft-spoken killer, who says he did it because “God told me to.” A religious Catholic suffering a crisis of faith, Nicholas gets the same response from a series of other mass murderers, including a cop played by Andy Kaufman, in his big screen debut, who lets loose during the St. Patrick’s Day Parade. (The next scene takes place at the Feast of San Gennaro, which is held every September in Little Italy, but it’s clear that six months have not elapsed, so we’ll give Cohen, a native of Washington Heights, poetic license in this case.) As Lo Bianco gets deeper and deeper into the mystery that involves an odd, cultlike figure named Bernard Phillips (Richard Lynch), he also has to deal with his estranged wife, Martha (Sandy Dennis), and his younger girlfriend, Casey Forster (Deborah Raffin). As he gets closer to the truth, he is forced to look deep into his soul amid all the madness. God Told Me To is shot by cinematographer Paul Glickman guerrilla style primarily without city permits and using a handheld camera, keeping the viewer off balance; the choppy editing by Michael D. Corey, Arthur Mandelberg, and William J. Waters doesn’t help smooth things out. The production values are quintessential low-budget mid-’70s, eliciting screams not of horror but of campy enjoyment among the middle-aged, who grew up watching these offbeat films at offbeat times in wood-paneled basements. Inspired by the Bible and one of the very first “aliens visited Earth!” books, Erich von Däniken’s bestselling Chariots of the Gods, Cohen, a producer, director, and writer who made such other low-budget faves as Black Caesar, It’s Alive, Q, The Stuff, and The Masters of Horror episode Pick Me Up, creates some intense scenes, including a hellish visit to a burning underground lair, as the twisting plot enters sci-fi territory involving a very special vagina.

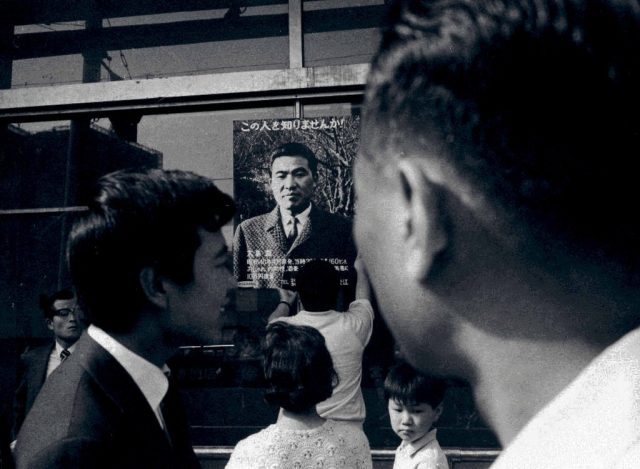

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On February 2, Japan Society is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of its Monthly Classics series; it will be followed on February 21 with “Directing Godzilla: The Life of Filmmaker Ishirō Honda,” a talk with Steve Ryfle, author of Ishirō Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, moderated by Film Forum repertory programming director Bruce Goldstein, whose Rialto Pictures released the film in theaters in 2004 and 2014, followed by a book signing and reception with many old Godzilla posters and memorabilia items on view.

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On February 2, Japan Society is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of its Monthly Classics series; it will be followed on February 21 with “Directing Godzilla: The Life of Filmmaker Ishirō Honda,” a talk with Steve Ryfle, author of Ishirō Honda: A Life in Film, From Godzilla to Kurosawa, moderated by Film Forum repertory programming director Bruce Goldstein, whose Rialto Pictures released the film in theaters in 2004 and 2014, followed by a book signing and reception with many old Godzilla posters and memorabilia items on view.