Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) run away to start a new life in Summer with Monika

SUMMER WITH MONIKA (SOMMAREN MED MONIKA) (Ingmar Bergman, 1953)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

February 23, 24, 26, 27, March 3

Series runs February 7 – March 15

212-727-8110

filmforum.org

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman shocked the film world in 1953 with the controversial Summer with Monika, the tale of two young lovers who run away from their families and go on a brief but intense sexual adventure. The film featured full-frontal nudity by Harriet Andersson, with whom Bergman had a short relationship; the movie was actually edited down by distributor Kroger Babb to focus on the sex and nudity, renaming it Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl! and marketing it to US audiences as an exploitation picture. But Film Forum is screening the superb original version as part of its five-week centennial celebration of Bergman’s birth. Based on the 1951 novel by Per Anders Fogelström, Summer with Monika takes place in a working-class area of Stockholm, where Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) toil away in a glassware factory. Harry lives with his ailing father (Georg Skarstedt), while Monika sleeps in her family’s kitchen. Both teens are bored with their already dull and unfulfilling lives. So when they meet in a café, the bold, forward Monika lures the shy, fragile Harry into what begins as a summer of fun, as they steal Harry’s father’s boat and head out to their own private hideaway, but ends up as something very different. Bergman boils down an entire relationship — courtship, romance, children, breakup, in a way a precursor to his later epic, Scenes from a Marriage — into ninety-seven sharp, intuitive moments, turning clichéd plot twists into subtle statements on life and family. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer shoots the film in a dark, gloomy black-and-white, with stark close-ups — Monika stares directly into the camera at one point, challenging the audience — and long shots of water and nature, while Erik Nordgren’s score is kept spare, with Bergman favoring natural sound and light.

Swedish director Ingmar Bergman shocked the film world in 1953 with the controversial Summer with Monika, the tale of two young lovers who run away from their families and go on a brief but intense sexual adventure. The film featured full-frontal nudity by Harriet Andersson, with whom Bergman had a short relationship; the movie was actually edited down by distributor Kroger Babb to focus on the sex and nudity, renaming it Monika, the Story of a Bad Girl! and marketing it to US audiences as an exploitation picture. But Film Forum is screening the superb original version as part of its five-week centennial celebration of Bergman’s birth. Based on the 1951 novel by Per Anders Fogelström, Summer with Monika takes place in a working-class area of Stockholm, where Harry (Lars Ekborg) and Monika (Harriet Andersson) toil away in a glassware factory. Harry lives with his ailing father (Georg Skarstedt), while Monika sleeps in her family’s kitchen. Both teens are bored with their already dull and unfulfilling lives. So when they meet in a café, the bold, forward Monika lures the shy, fragile Harry into what begins as a summer of fun, as they steal Harry’s father’s boat and head out to their own private hideaway, but ends up as something very different. Bergman boils down an entire relationship — courtship, romance, children, breakup, in a way a precursor to his later epic, Scenes from a Marriage — into ninety-seven sharp, intuitive moments, turning clichéd plot twists into subtle statements on life and family. Cinematographer Gunnar Fischer shoots the film in a dark, gloomy black-and-white, with stark close-ups — Monika stares directly into the camera at one point, challenging the audience — and long shots of water and nature, while Erik Nordgren’s score is kept spare, with Bergman favoring natural sound and light.

Harriet Andersson stars as a fierce, independent spirit in Ingmar Bergman’s Summer with Monika

Andersson, who would go on to make many more films with Bergman, including Sawdust and Tinsel, Smiles of a Summer Night, Cries and Whispers, and Fanny and Alexander, is enticing as Monika, who doesn’t mind stepping on people’s souls while asserting herself as an independent woman, while Ekborg, who had a small part in Bergman’s The Magician, shows plenty of vulnerability as Harry, who wants to do the right thing and is ready to at least try to be a grown-up when things get complicated. The film is still shocking after all these years, and still rings true. “I want summer to go on just like this,” Monika says. But there are always other seasons, and more summers, to come. Summer with Monika is screening February 23, 24, 26, and 27 and March 3 in the Film Forum series, which continues through March 15 with such other seasonal Bergman works as Smiles of a Summer Night, Summer Interlude, and Autumn Sonata.

Liv Ullmann and Ingmar Bergman alter ego Max von Sydow pull up to shore in Hour of the Wolf

HOUR OF THE WOLF (VARGTIMMEN) (Ingmar Bergman, 1968)

Film Forum

February 24 and 28, March 1, 2, 5, 9

filmforum.org

One of Ingmar Bergman’s most critically polarizing films — the director himself wrote, “No, I made it the wrong way” three years after its release — Hour of the Wolf is a gripping examination of an artist’s psychological deterioration. Bergman frames the story as if it’s a true tale being told by Alma Borg (Liv Ullmann) based on her husband Johan’s (Max von Sydow) diary, which she has given to the director. In fact, as this information is being shown in words onscreen right after the opening credits, the sound of a film shoot being set up can be heard behind the blackness; thus, from the very start, Bergman is letting viewers know that everything they are about to see might or might not be happening, blurring the lines between fact and fiction in the film itself as well as the story being told within. And what a story it is, a gothic horror tale about an artist facing both a personal and professional crisis, echoing the life of Bergman himself. Johan and Alma, who is pregnant (Ullmann was carrying Bergman’s child at the time), have gone to a remote island where he can pursue his painting in peace and isolation. But soon Johan is fighting with a boy on the rocks, Alma is getting a dire warning from an old woman telling her to read Johan’s diary, and the husband and wife spend some bizarre time at a party in a castle, where a man walks on the ceiling, a dead woman arises, and other odd goings-on occur involving people who might be ghosts. Bergman keeps the protagonists and the audience guessing as to what’s actually happening throughout: The events could be taking place in one of the character’s imaginations or dreams (or nightmares), they could be flashbacks, or they could be part of the diary come to life. Whatever it is, it is very dark, shot in an eerie black-and-white by Sven Nykvist, part of a trilogy of grim 1968-69 films by Bergman featuring von Sydow and Ullmann that also includes Shame and The Passion of Anna. Today, Hour of the Wolf feels like a combination of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining with elements of Mozart’s The Magic Flute — which Bergman would actually adapt for the screen in 1975 and features in a key, extremely strange scene in Hour of the Wolf. But in Bergman’s case, all work and no play does not make him a dull boy at all. Hour of the Wolf is screening February 24 and 28 and March 1, 2, 5, and 9 in Film Forum’s centennial celebration of the birth of Ingmar Bergman.

One of Ingmar Bergman’s most critically polarizing films — the director himself wrote, “No, I made it the wrong way” three years after its release — Hour of the Wolf is a gripping examination of an artist’s psychological deterioration. Bergman frames the story as if it’s a true tale being told by Alma Borg (Liv Ullmann) based on her husband Johan’s (Max von Sydow) diary, which she has given to the director. In fact, as this information is being shown in words onscreen right after the opening credits, the sound of a film shoot being set up can be heard behind the blackness; thus, from the very start, Bergman is letting viewers know that everything they are about to see might or might not be happening, blurring the lines between fact and fiction in the film itself as well as the story being told within. And what a story it is, a gothic horror tale about an artist facing both a personal and professional crisis, echoing the life of Bergman himself. Johan and Alma, who is pregnant (Ullmann was carrying Bergman’s child at the time), have gone to a remote island where he can pursue his painting in peace and isolation. But soon Johan is fighting with a boy on the rocks, Alma is getting a dire warning from an old woman telling her to read Johan’s diary, and the husband and wife spend some bizarre time at a party in a castle, where a man walks on the ceiling, a dead woman arises, and other odd goings-on occur involving people who might be ghosts. Bergman keeps the protagonists and the audience guessing as to what’s actually happening throughout: The events could be taking place in one of the character’s imaginations or dreams (or nightmares), they could be flashbacks, or they could be part of the diary come to life. Whatever it is, it is very dark, shot in an eerie black-and-white by Sven Nykvist, part of a trilogy of grim 1968-69 films by Bergman featuring von Sydow and Ullmann that also includes Shame and The Passion of Anna. Today, Hour of the Wolf feels like a combination of Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining with elements of Mozart’s The Magic Flute — which Bergman would actually adapt for the screen in 1975 and features in a key, extremely strange scene in Hour of the Wolf. But in Bergman’s case, all work and no play does not make him a dull boy at all. Hour of the Wolf is screening February 24 and 28 and March 1, 2, 5, and 9 in Film Forum’s centennial celebration of the birth of Ingmar Bergman.

Liv Ullmann and Bibi Andersson come together in Ingmar Bergman’s dazzling Persona

PERSONA (Ingmar Bergman, 1966)

Film Forum

February 23-25, March 1-3, 7

filmforum.org

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.

A young boy reaches out in avant-garde Bergman masterpiece, spectacularly photographed by Sven Nykvist

Bergman muse Liv Ullmann stars as Elisabet Vogler, an actress who suddenly stops talking while onstage in the midst of a play and continues her silence as she is hospitalized in an institution. Her doctor (Margaretha Krook) is sure there is nothing seriously wrong with Elisabet, that her refraining from speech is a choice based on the horrors she sees in the world. “Reality is diabolical,” she tells her, before sending Elisabeth and Nurse Alma (Bibi Andersson) to her cottage on Fårö Island, hoping the isolation will help ease her fears. On the island, Alma opens up about her own life, particularly about sex, but as the two women grow extremely close, they are also torn apart, both by the narrative and the celluloid, which rips and burns halfway through, setting up a chilling conclusion that is part existential thriller, part ghost story, and very much a sharp, incisive look deep into the human psyche. Filmed in haunting black-and-white by Sven Nykvist and including numerous dazzling, experimental shots, Persona is a grand cinematic achievement, an intense work that expanded the boundaries of what the medium can do. In his 1990 book, Images: My Life in Film, Bergman wrote, “Today I feel that in Persona — and later in Cries and Whispers — I had gone as far as I could go. And that in these two instances, when working in total freedom, I touched wordless secrets that only the cinema can discover.” Indeed, “wordless secrets” abound in Persona, one of Bergman’s most penetrating and mesmerizing tales. Even the title holds additional meaning, as “persona,” in Latin, originally referred to the mask an actor wore that represented the character they were playing onstage. Persona is screening February 23-25 and March 1-3 and 7 in Film Forum’s Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective.

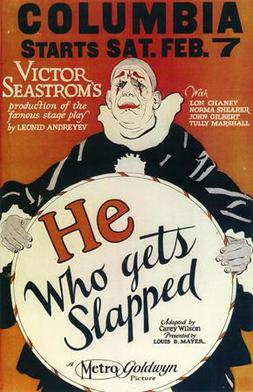

In conjunction with its Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective, Film Forum is presenting “Victor Sjöström: The Screen’s First Master,” five films by the Swedish master who was Bergman’s mentor and appeared in two of his films, To Joy and Wild Strawberries. The mini-festival continues February 26 with Sjöström’s second English-language film and MGM’s first-ever picture, He Who Gets Slapped, which Sjöström wrote and directed under the Americanized last name Seastrom. Lon Chaney stars as scientist Paul Beaumont, who is excited when he makes a major discovery about the origins of humankind, but his wealthy benefactor, Baron Regnard (Marc McDermott), steals his work and presents it to the Academy, slapping Beaumont’s face to great hilarity and applause when the scientist claims it is actually his theory. After Regnard also steals Beaumont’s wife, Maria (Ruth King), the sad-sack scientist runs off and joins the circus, rising in stature as He, a clown who gets slapped over and over and over as a kind of self-flagellation, much to the delight of audiences everywhere. “Over a hundred slaps last night, He,” fellow clown Tricaud (Ford Sterling) tells him. “You lucky fellow! Soon you’ll be getting famous! But you know what they like — there’s nothing makes people laugh so hard as seeing someone else get slapped!” The distraught clown perks up when Consuelo (Norma Shearer) joins the circus as a bareback rider who will team up with Bezano (John Gilbert), but He — Beaumont doesn’t even exist anymore — gets mad when he finds out that Consuelo’s father, Count Mancini (Tully Marshall), has sold her to the circus because he is nearly broke — and shortly after that the Count is pimping his daughter off to none other than the Baron, something that neither Bezano nor He is about to let happen.

In conjunction with its Ingmar Bergman Centennial Retrospective, Film Forum is presenting “Victor Sjöström: The Screen’s First Master,” five films by the Swedish master who was Bergman’s mentor and appeared in two of his films, To Joy and Wild Strawberries. The mini-festival continues February 26 with Sjöström’s second English-language film and MGM’s first-ever picture, He Who Gets Slapped, which Sjöström wrote and directed under the Americanized last name Seastrom. Lon Chaney stars as scientist Paul Beaumont, who is excited when he makes a major discovery about the origins of humankind, but his wealthy benefactor, Baron Regnard (Marc McDermott), steals his work and presents it to the Academy, slapping Beaumont’s face to great hilarity and applause when the scientist claims it is actually his theory. After Regnard also steals Beaumont’s wife, Maria (Ruth King), the sad-sack scientist runs off and joins the circus, rising in stature as He, a clown who gets slapped over and over and over as a kind of self-flagellation, much to the delight of audiences everywhere. “Over a hundred slaps last night, He,” fellow clown Tricaud (Ford Sterling) tells him. “You lucky fellow! Soon you’ll be getting famous! But you know what they like — there’s nothing makes people laugh so hard as seeing someone else get slapped!” The distraught clown perks up when Consuelo (Norma Shearer) joins the circus as a bareback rider who will team up with Bezano (John Gilbert), but He — Beaumont doesn’t even exist anymore — gets mad when he finds out that Consuelo’s father, Count Mancini (Tully Marshall), has sold her to the circus because he is nearly broke — and shortly after that the Count is pimping his daughter off to none other than the Baron, something that neither Bezano nor He is about to let happen.

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.

Ingmar Bergman’s magnificently complex 1966 avant-garde masterpiece, Persona, is not just about the relationship between an actress who has suddenly decided to stop speaking and the young nurse caring for her but about the very power of film as a narrative device able to explore and examine the psychological behavior of characters both fictional and real. Persona opens with mysterious, penetrating music by Lars Johan Werle joined by the sound and image of a movie projector as the reel counts down from ten, featuring snippets of an erect male member, a cartoon, a child’s hands, a comedic silent ghost story, a tarantula, a bleeding slaughtered lamb, and a nail being hammered through a man’s palm before the camera takes viewers inside a hospital where a boy in a bed (Jörgen Lindström) starts reading Mikhail Lermontov’s mid-nineteenth-century book A Hero of Our Time, which the author describes as “a portrait, but not of one man only. . . . You will tell me, as you have told me before, that no man can be so bad as this; and my reply will be: ‘If you believe that such persons as the villains of tragedy and romance could exist in real life, why can you not believe in the reality of Pechorin?’ . . . Is it not because there is more truth in it than may be altogether palatable to you?” That passage relates to Bergman’s oeuvre as a whole but particularly to Persona, a film about identity, storytelling, and the medium itself.

Colombian writer-director Ciro Guerra takes viewers on a spectacular journey through time and space and deep into the heart of darkness in the extraordinary Embrace of the Serpent. Guerra’s Oscar-nominated film, the first to be shot in the Colombian Amazon in thirty years, opens with a 1909 quote from explorer Theodor Koch-Grünberg: “It is not possible for me to know if the infinite jungle has started on me the process that has taken many others to complete and irremediable insanity.” Inspired by the real-life journals of Koch-Grünberg and botanist and explorer Richard Evans Schultes, Guerra poetically shifts back and forth between two similar trips down the Vaupés River, both led by the same Amazonian shaman, each time guiding a white scientist on a perilous expedition in a long, narrow canoe. Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, ailing white ethnologist Theo (Jan Bijvoet) and his native aid, Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), seek the help of Karamakate (Nilbio Torres), a shaman wholly suspicious of whites and who believes he is the last of his tribe. However, Theo claims he knows where remnants of Karamakate’s people live and will show him in return for helping him find the magical and mysterious hallucinogenic Yakruna plant that Theo thinks can cure his illness. Forty years later, white botanist Evan (Brionne Davis) enlists Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar Salvador) to locate what is thought to be the last surviving Yakruna plant, which he hopes will finally allow him to dream in order to heal his soul. Evoking such films as Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Embrace of the Serpent makes the rainforest itself a character, shot in glorious black-and-white by David Gallego (Cecilia, Violencia) in a sparkling palette reminiscent of the work of Brazilian photographer

Colombian writer-director Ciro Guerra takes viewers on a spectacular journey through time and space and deep into the heart of darkness in the extraordinary Embrace of the Serpent. Guerra’s Oscar-nominated film, the first to be shot in the Colombian Amazon in thirty years, opens with a 1909 quote from explorer Theodor Koch-Grünberg: “It is not possible for me to know if the infinite jungle has started on me the process that has taken many others to complete and irremediable insanity.” Inspired by the real-life journals of Koch-Grünberg and botanist and explorer Richard Evans Schultes, Guerra poetically shifts back and forth between two similar trips down the Vaupés River, both led by the same Amazonian shaman, each time guiding a white scientist on a perilous expedition in a long, narrow canoe. Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century, ailing white ethnologist Theo (Jan Bijvoet) and his native aid, Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), seek the help of Karamakate (Nilbio Torres), a shaman wholly suspicious of whites and who believes he is the last of his tribe. However, Theo claims he knows where remnants of Karamakate’s people live and will show him in return for helping him find the magical and mysterious hallucinogenic Yakruna plant that Theo thinks can cure his illness. Forty years later, white botanist Evan (Brionne Davis) enlists Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar Salvador) to locate what is thought to be the last surviving Yakruna plant, which he hopes will finally allow him to dream in order to heal his soul. Evoking such films as Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo and Aguirre, the Wrath of God and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now, Embrace of the Serpent makes the rainforest itself a character, shot in glorious black-and-white by David Gallego (Cecilia, Violencia) in a sparkling palette reminiscent of the work of Brazilian photographer