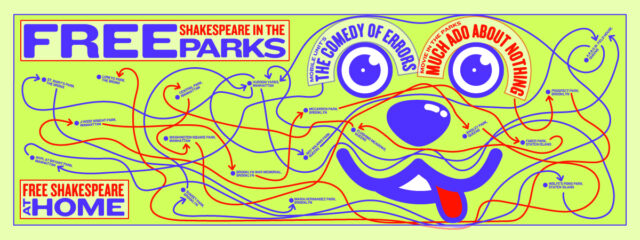

Two essential healthcare workers take a much-deserved brief break in a Wuhan hospital in 76 Days

76 DAYS (Hao Wu, Weixi Chen, and Anonymous, 2020)

China Institute in America

100 Washington St. (use 40 Rector St. entrance)

Wednesday, June 20, $12, 6:00

chinainstitute.org/events

www.76daysfilm.com

The prospect of sitting through a ninety-minute documentary about essential healthcare workers in four hospitals in Wuhan fighting in the early days of Covid-19, during the city’s seventy-six-day lockdown, might seem daunting. But what could have been a difficult, emotional, and political roller coaster about fear and anger, government lies and finger pointing turns out to be a deeply affecting film that celebrates our most basic hopes and humanity.

Chinese director Hao Wu was researching a film about pandemics when, in mid-February, he came upon footage being shot by a pair of reporters in Wuhan, Weixi Chen and a man who has decided to remain anonymous. They had been given full access to four hospitals, where they followed doctors, nurses, patients, and family members for several months. There are no talking heads, and no one speaks directly to the camera; instead, 76 Days offers a fly-on-the-wall perspective that manages to be as uplifting as it is frightening.

The film opens like a sci-fi thriller, as an unidentified group of people in head-to-toe protective gear that includes light-blue masks, long face shields, white Hazmat suits, and blue footies comforts a distraught colleague who is prevented from saying goodbye to her father, who has just died from the novel coronavirus. Near the end of the scene, one of her coworkers tries to calm her down, saying, “We don’t want to see you in distress or pain. What will we do if you fall sick? We all have to work in the afternoon.” Moments later, sick people are banging on a door of the hospital to be let in, like a crowd trying to escape a coming zombie apocalypse, while two workers decide who to admit first. Those exchanges set the stage for the rest of the film, in which doctors and nurses go about their business with a relatively relaxed demeanor, displaying endless empathy and compassion as they care for scared patients with uncertain futures.

Wu focuses on a few specific cases that serve to represent the crisis as a whole, following an elderly couple who both have the virus and are not permitted to see each other even though they are on the same floor, and a young couple who are forced to quarantine in their apartment after the woman gives birth to a baby girl, unable to see their newborn for two weeks. While the nurses fall in love with the infant, who must stay in an incubator and whom they name Little Penguin, the workers have their hands full with the old man, who constantly tries to leave the hospital and doesn’t seem capable of wearing his mask correctly, if at all.

Doctors and nurses in Wuhan care for Covid patients, displaying empathy and compassion during seventy-six-day lockdown

The genuine kindness and concern displayed by the hospital employees is, well, infectious. They are risking their lives at every moment; each encounter is fraught with the possibility that they could contract the virus even with all the PPE. It’s hard not to cringe when they feed the old man, wipe the face of the infant, or use a patient’s phone to call a relative with news, because the reality is that people die from this disease, and Wu is not afraid to show that. It’s a riveting film that immerses you in this global emergency that started right there, at that time; if this doesn’t make you wear a mask, wash your hands, observe social distance protocols, and avoid gathering with others indoors, I don’t know what will.

We also see the empty streets and highways of Wuhan, a city of eleven million people, deserted, with signs advising, “Staying home makes a happy family.” All the action is happening in the hospitals, where the doctors and nurses bond with themselves and the patients, decorate their white Hazmat suits with drawings and sayings (“Clay Pot Chicken: I miss you”), and caution everyone to “be extra vigilant.” The crisis may be over, but those are still words to live by. Winner of the Best Cinematography award at DOC NYC 2020 and nominated for a Best Documentary Gotham Award, 76 Days is screening June 20 at 6:00 at China Institute and will be followed by a Q&A with Wu and film scholar Karen Ma.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]