Six fairy-tale characters reimagine their future in Once Upon a One More Time (photo by Matthew Murphy)

ONCE UPON A ONE MORE TIME

Marquis Theatre

210 West Forty-Sixth St. between Seventh & Eighth Aves.

Tuesday – Saturday through September 3, $59.75-$319.50

onemoretimemusical.com

In May, I wrote about a pair of jukebox musicals, the extremely disappointing A Beautiful Noise: The Neil Diamond Musical, which unsurprisingly received no Tony nominations, and the absolutely delightful & Juliet, which earned nine nods but unfortunately took home none. The former was a disjointed look at the life and career of the Brooklyn-born megastar, while the latter was a clever follow-up to Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in which his wife, Anne Hathaway, decides to pen a sequel in which Juliet survives and, leaving behind the dead Romeo, heads to Paris to start a new life, set to existing tunes written or cowritten by Swedish producer Max Martin for the Backstreet Boys, Robyn, Demi Lovato, Bon Jovi, Katy Perry, *NSYNC, Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, and others.

Last week I encountered a similar situation when I saw two new musicals, one an unsatisfying biographical chronicle, the other a surprisingly clever reimagining of a fairy-tale world using nothing but songs by Spears, the Princess of Pop, who has sold nearly 150 million records but has won more Golden Raspberries (3) than Grammys (1).

At the Marquis Theatre, Once Upon a One More Time is a load of fun despite a fairly ludicrous setup: After generations of following the rules enforced by the Narrator (Adam Godley), who makes sure to keep every female character in her place from story to story, Cinderella (Briga Heelan), Snow White (Aisha Jackson), Rapunzel (Gabrielle Beckford), Sleeping Beauty (Ashley Chiu), Princess Pea (Morgan Whitley), and Little Mermaid (Lauren Zakrin) start to realize there might be something else out there for them after the O.F.G. — the Original Fairy Godmother (Brooke Dillman) — gives Cin a copy of Betty Friedan’s 1963 game-changer, The Feminine Mystique, which helped usher in second-wave feminism. And they explore their situations through such Spears hits as “Lucky,” “Toxic,” “Womanizer,” “Oops! . . . I Did It Again,” and “. . . Baby One More Time.”

Prince Charming (Justin Guarini) turns out to be quite the dog in Britney Spears musical (photo by Matthew Murphy)

Cinderella is the first to consider that she might have a choice in her future, which upsets the Narrator. “Yes. Listen, I’ve been doing this a long time. And believe me, if I change so much as an intonation, the children go full Rumpelstiltskin,” he tells her. “They want things the same, every time. The narrative is very clear. We’re not here to make fairy tales, we’re here to follow them. Don’t overthink it. Oh, and don’t furrow your brow! We want you delivering lines, not wearing them. There. Better. Happy ever after.”

When Snow notices that Cin appears to be a bit off, she says, “Hey, you seem ‘stuck.’ Doc gives me pills for when I get like that.” Cinderella turns her down, then points out that Snow White’s latest needlepoint, “Happy ever after,” is filled with typos. Snow replies, “Huh. I guess neither of us knows what happy ever after’s supposed to look like. . . . All right, I gotta go get chased through the woods by a terrifying man in pitch blackness.”

When Cin discovers that her Prince Charming (Justin Guarini) is also Snow’s Faithful, the misogyny that is baked into traditional fairy tales rises to the surface and begins to turn things upside down and inside out. Not only do the young women — including Belle (Liv Battista), Goldilocks (Amy Hillner Larsen), and Red (Justice Moore) — start reevaluating the state of their being, but Prince Erudite (Ryan Steele) and Clumsy (Nathan Levy) wonder if they can explore their potential relationship as well. Meanwhile, Cinderella’s Stepmother (Jennifer Simard) and her two stepsisters, Belinda (Ryann Redmond) and Betany (Tess Soltau), lie in wait, willing to play by the rules in order to land Prince Charming or even Prince Brawny (Joshua Daniel Johnson), Mischievous (Kevin Trinio Perdido), Gregarious (Mikey Ruiz), Suave (Josh Tolle), or Affable (Stephen Scott Wormley).

Cinderella (Briga Heelan) discovers a whole new world in a book by Betty Friedan (photo by Matthew Murphy)

If you took Six, & Juliet, Into the Woods, Head Over Heels, Wicked, and Bad Cinderella and put them into a blender, you would come up with something like Once Upon a One More Time. Not all of it works; at two and a half hours with intermission, it is repetitive, and the last fifteen minutes or so should be chopped off, as it basically explains to us what we’ve already seen. The whole Betty Friedan element is still puzzling to me — I understand why they chose that book, but the whole idea of making it a key part of the plot and (sort of) getting away with it is mind-boggling to me — as are the Narrator’s threats to send rule breakers to a place called Story’s End.

Jon Hartmere’s (bare, The Upside) book is otherwise witty and clever, no doubt helped by five-time Tony nominee David Leveaux serving as creative consultant. The crack ten-piece band keeps Spears’s songs down to earth, avoiding haughty orchestrations, although several ballads threaten to go over the top. In their first Broadway show, directors and choreographers Keone and Mari Madrid (Beyond Babel, The Karate Kid) cut loose with ecstatic Spears-inspired dance numbers performed by an exuberant cast.

Anna Fleischle’s appealing set features trees and the facades of houses raised and lowered, an elegant staircase, a multilevel platform laden with stage lighting, a balcony, windowlike screens in the back, and a giant quill in a bubble hanging from the ceiling, daring anyone to grab it and rewrite the fairy tales. Sven Ortel’s projections range from the night sky to scary woods to magic castles, with fanciful lighting and plenty of glowing spots by Kenneth Posner and raucous sound by Andrew Keister.

Many of Loren Elstein’s costumes are based on outfits Spears wore in videos and concerts, with wigs by Nikiya Mathis that further our immersion into all things Britney, as if each fairy-tale character represents a separate part of her history. In her Broadway debut, Heelan is absolutely delightful as Cinderella, a stand-in for anyone ready to burst out with their own story. Jackson (Paradise Square, Waitress) is lovely as Cin’s best friend, Guarini (American Idiot, Wicked) has a field day as the self-absorbed, selfish prince who gets to belt out “Oops! . . . I Did It Again,” and two-time Tony nominee Godley (The Lehman Trilogy, Anything Goes) is just right as the Narrator, who is terrified of change. But two-time Tony nominee Simard (Company, Mean Girls), as she so often does, steals the show as the evil stepmother who always has a plan up her corset.

Once Upon a One More Time bites off more than it can chew, but it’s no poison apple it’s nibbling on but is instead shiny, fresh, and crisp, even if it’s occasionally sour.

While the show is not about Spears’s controversial life — it arrives on Broadway less than two years after Spears was freed from her father’s conservatorship — there are fairy-tale aspects to her early career, followed by bittersweet personal and professional entanglements that titillated the public and impacted her reputation. Once Upon a One More Time helps reestablish that original image.

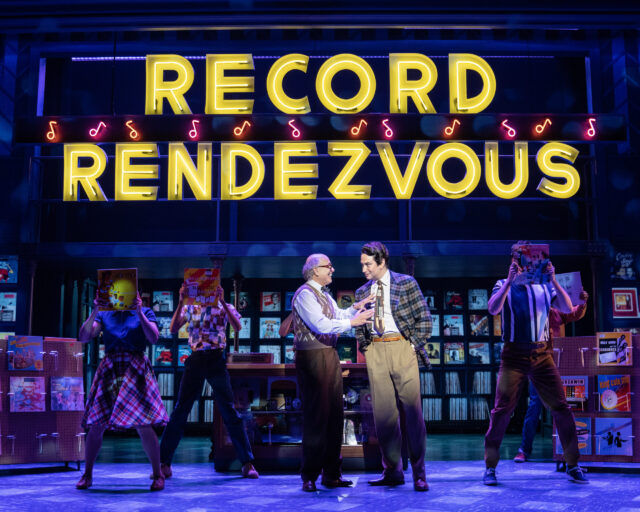

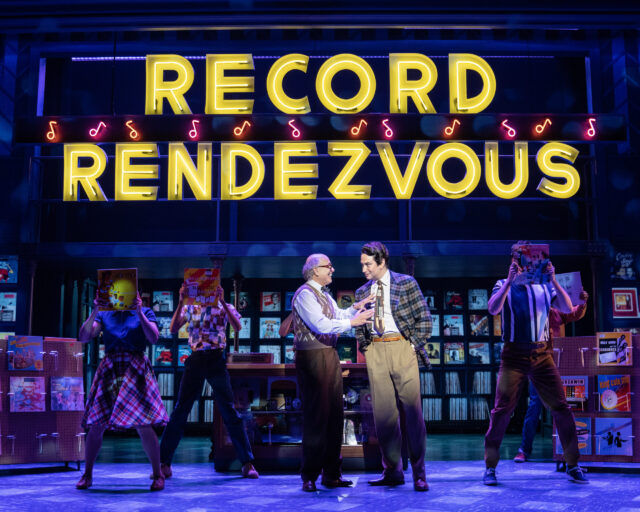

Leo Mintz (Joe Pantoliano) and Alan Freed (Constantine Maroulis) come up with a plan to spread the gospel of rock and roll in musical (photo © Joan Marcus 2023)

ROCK & ROLL MAN

New World Stages

340 West 50th St. between Eighth & Ninth Aves.

Wednesday – Monday through September 1, $90-$164

rockandrollmanthemusical.com

www.newworldstages.com

When my mother was a teenager in the mid-1950s, she would sneak out of her apartment and catch rock and roll shows at the Brooklyn Paramount, seeing all the greats, the originators of the art form. I grew up with that music, treasuring two small boxes of 45s that contained many of the best singles ever recorded, by Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, the Moonglows, the Coasters, the Platters, the Drifters, and others.

All of those artists and more are featured in Rock & Roll Man, a new musical about legendary DJ Alan Freed (Constantine Maroulis) that is making its New York premiere at New World Stages. It opens at the Paramount with Freed’s 1958 Holiday Rock and Roll Extravaganza, kicking off with my favorite song from that era, “Sh-Boom” by the Bronx-based Chords: “Life could be a dream / If I could take you up in paradise up above / If you would tell me I’m the only one that you love / Life could be a dream, sweetheart.” Unfortunately, after a promising beginning, the rest of the show proves not to be a dream of paradise.

The goofy premise is that on the last night of his life, January 20, 1965, amid Beatlemania and the Vietnam War, the Pennsylvania-born Freed is dreaming that he is being tried in an imaginary Court of Public Opinion by Judge Mental (Eric B. Turner) in the trial of The World versus Alan Freed; with the help of his lawyer, Little Richard (Rodrick Covington), Freed must defend his legacy against relentless prosecutor J. Edgar Hoover (Bob Ari), who has charged him with “the destruction of the American way of life by inventing the genre of music which you named rock and roll,” claiming that Freed is a “fraud . . . a modern day snake oil salesman who concocted this foul form of music solely for the purpose of self-promotion and illicit profit . . . then foisted it on our unsuspecting youth, manipulating them into a world of juvenile delinquency, alcohol, narcotics, and . . . SEX!!!!!”

Through flashbacks, Freed returns to Cleveland, where he got his start in radio, teaming up with Record Rendezvous owner and station advertiser Leo Mintz (Joe Pantoliano) to bring rock and roll to the younger generation. Freed immediately draws an integrated audience, with Black and white teenagers listening to his Moondog Show, hanging out at the record store, and going to concerts hosted by Freed and featuring such acts as LaVern Baker (Valisia LeKae).

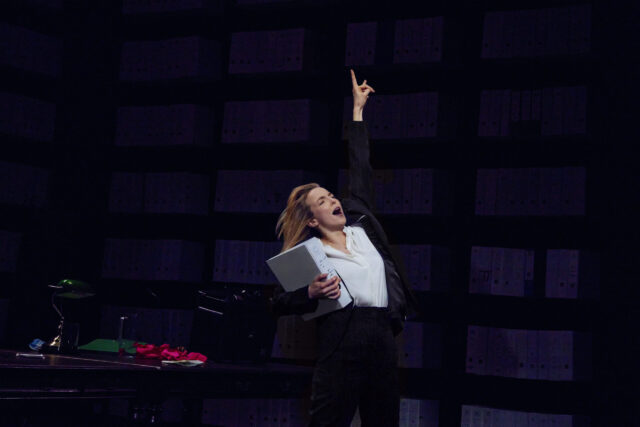

Constantine Maroulis stars as controversial deejay Alan Freed in Rock & Roll Man (photo © Joan Marcus 2023)

Freed hits the big time when he moves to New York City and WINS, teaming up with Roulette Records owner and Birdland cofounder Morris Levy (Pantoliano), who allegedly associated with the Mafia. When a district attorney asks him, “Is it true you associate with known mobsters like Vinnie the Chin Gigante and other members of the Gambino crime family?,” he replies, “Look, I grew up in New York City. I know a lot of different people, including a few of the gentlemen you just mentioned. I also know Cardinal Spellman. That don’t make me a Catholic. And by the way, the cardinal loves me. He’s a real mensch.”

Freed and Levy present Little Richard, Frankie Lymon (Jamonté) and the Teenagers, Buddy Holly (Andy Christopher), Chuck Berry (Matthew S. Morgan), Jerry Lee Lewis (Dominique Scott), Bo Diddley (Eric B. Turner), and other breakthrough favorites, fighting off the trend of Caucasian crooners like Pat Boone (Christopher) “sucking the soul [right out of Little Richard’s] songs . . . bleaching ’em lily white,” with the original artists not seeing a penny in royalties when they’re played on the radio or on TV. Introducing Boone’s hot new song “Ain’t That a Shame” — first recorded by Fats Domino, who wrote it with Dave Bartholomew — on American Bandstand, host Dick Clark (Scott) calls himself “one of the good guys playing good clean American rock and roll for all you good clean American teenagers.”

But white performers and producers weren’t the only ones on the take; as Freed keeps growing more successful, FBI chief Hoover comes after him, accusing him of not only corrupting children but of accepting payola, setting up a final showdown.

By including new songs alongside classic oldies, Rock & Roll Man sets itself up with a major problem: Gary Kupper’s (Freckleface Strawberry, Consumer Behavior) original music and lyrics are vastly overshadowed by “Sixty Minute Man,” “Rocket 88,” “Lucille,” “See See Rider,” and “Smoke Gets in Your Eyes.” Covington and LeKae rip it up as Little Richard and LaVern Baker, respectively, with strong support from Turner as a singer in multiple groups, far outshining Morgan as Berry and Scott as Jerry Lee. The show might have benefited from a more wide-ranging book from Kupper, Larry Marshak, and Rose Caiola, adding much-needed attention to Freed’s family life; there are perfunctory appearances by his daughter Alana (Anna Hertel) and his wife Jackie (Autumn Guzzardi) — which was not the name of any of his three wives. Notably, one of the producers is Colleen Freed, who is married to Alan’s son Lance from his first marriage.

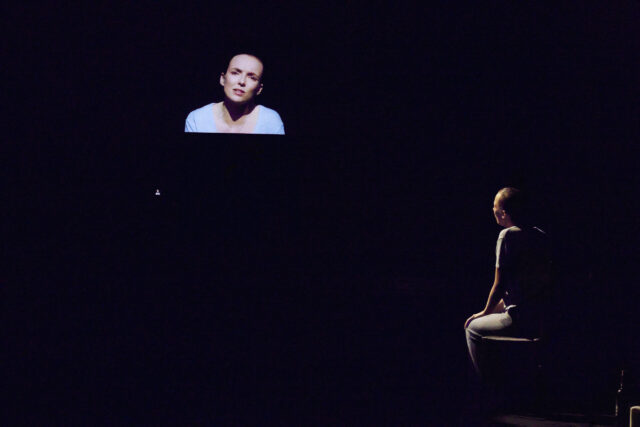

Rodrick Covington rips it up as Little Richard in Alan Freed biomusical (photo © Joan Marcus 2023)

Director Randal Myler (It Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues, Hank Williams: Lost Highway), music supervisor and arranger Dave Keyes (with Kupper), and choreographer Stephanie Klemons only lift the show out of first gear when the classic songs are performed, with Keyes on synth, George Naha on guitar, Lee Nadel on bass, Mark Ivan Gross Sr. on reeds, and Rocky Bryant on drums and percussion.

Tim Mackabee’s two-level set morphs from record store to nightclub to radio station to concert stage. Leon Dobkowski’s costumes capture the feel of the era, enhanced by Kelley Jordan’s fab wigs. The projections are by Christopher Ash, with lighting by Matthew Richards and Aja M. Jackson and sound by Ed Chapman.

Tony nominee Maroulis (Rock of Ages, Jekyll & Hyde) has a charm to him but is not given enough character depth, falling short of Tim McIntire’s more energetic portrayal of Freed in Floyd Mutrux’s 1978 film, American Hot Wax. Emmy winner Pantoliano (Great Kills, Frankie and Johnny in the Claire de Lune) seems more at home as Levy than Mintz, and he sings, too. Ari (Bells Are Ringing, Picasso at the Lapin Agile) is like a grizzly bear onstage as several villainous figures.

There’s no need to sneak out of your apartment to see Rock & Roll Man. If you need to hear “Tutti Frutti,” “Maybellene,” “Great Balls of Fire,” “Yakety Yak,” and “Why Do Fools Fall in Love” — and you do — you can always come over to my place and listen to the original pressings on my Victrola.