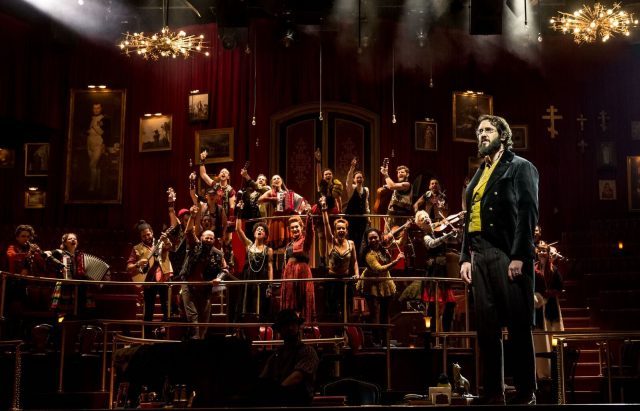

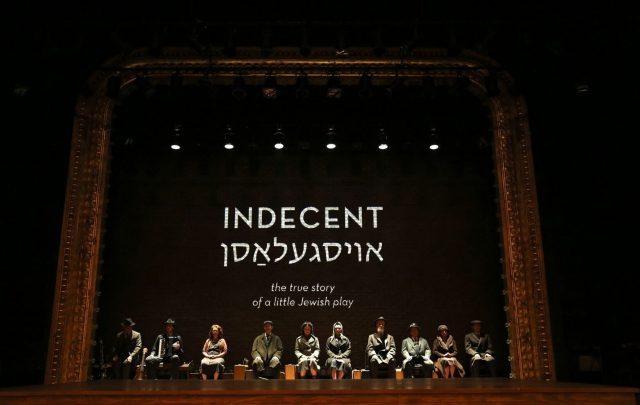

Indecent takes audiences behind the scenes of controversial drama GOD OF VENGEANCE (photo by Carol Rosegg)

Cort Theatre

138 West 48th St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through August 6, $39 – $129

indecentbroadway.com

In late 1922, Sholem Asch’s controversial 1907 Yiddish play, God of Vengeance, premiered in an English-language version at the Provincetown Playhouse in the Village. On February 19, 1923, it moved uptown to the Apollo Theatre on Broadway. On March 5, the cast and producer were indicted on obscenity charges. (The play closed on April 14.) Ninety-three years later, on April 27, 2016, Paula Vogel and Rebecca Taichman’s Indecent, about the making of God of Vengeance, opened at the Vineyard Theatre by Union Square Park. The following April, it moved uptown to the Cort Theatre on Broadway. On May 3, the show received three Tony nominations, including Best Play (Vogel, in her Broadway debut) and Best Director (Taichman). How times have changed. I was moved by Indecent when I saw it at the Vineyard last June. However, since then, I caught the New Yiddish Rep revival of God of Vengeance, and the new U.S. administration has clamped down on immigration while anti-Semitism is on the rise around the world. Those aspects have led me to fall in love with the Broadway version, which is bigger and better at the Cort. Richard Topol again stars as Lemml, an immigrant who is so taken with Asch’s (Max Gordon Moore) play that he becomes the stage manager for the show as it travels through Eastern Europe and ultimately to New York City; he also serves as the narrator, addressing the audience directly as he shares his memories — although he cannot remember how it all ends. (The audience, however, is unlikely to forget the elegiac, haunting conclusion.) In the play within a play, Yankl (Tom Nelis), a devout Jewish man, is running a brothel in his basement in order to be able to afford a better life for his daughter, Rifkele (Adina Verson), as well as a new Torah, which he hopes will protect her virtue. Much to his chagrin, however, Rifkele falls in love with Menke (Katrina Lenk), one of the prostitutes. Nelis is also Rudolph Schildkraut, the famous Austrian actor who headlined and directed the show. The famous lesbian kiss from God of Vengeance, one of the most romantic moments I have ever seen onstage, is handled beautifully by Pulitzer Prize winner Vogel (How I Learned to Drive, The Baltimore Waltz) and Taichman (How to Transcend a Happy Marriage, Familiar), as is the entire production.

Menke (Katrina Lenk) and Rifkele (Adina Verson) share a beautiful moment in Indecent (photo by Carol Rosegg)

As you enter the theater, the cast is already seated in a row of chairs at the back of the stage. There is a slightly raised platform in the center, where most of the action takes place. (The dark, ominous stage design is by Riccardo Hernandez.) Most of the dialogue is in English, with Tal Yarden’s projections explaining what language is actually being spoken. The play features several surreal elements, including the dispensation of sand from the characters’ sleeves, a clever use of suitcases, and sudden breakouts into joyous klezmer songs and Jewish folk dances during which a trio of musicians (clarinetist Matt Darriau, violinist Lisa Gutkin — who gets a bonus surprise — and accordionist Aaron Halva) gets involved. The choreography, which ranges from playful to portentous, is by David Dorfman; Christopher Akerlind’s stunning lighting is virtually a character unto itself. Much of the excellent cast is the same from the Vineyard, with standout performances by Topol (The Merchant of Venice, The Normal Heart), who is both observer and participant, and the sultry, sexy Lenk (Once, The Band’s Visit), who can set the hearts of men and women aflutter. The exhaustively researched Indecent, which was inspired by Taichman and Rebecca Rugg’s 2000 The People vs. The God of Vengeance at Yale, raises questions of freedom of speech, immigration, the suppression of art, homosexuality, and faith, as well as the power of theater itself. With all that’s going on in the world today, the play also serves as a warning that this could all happen again if we’re not careful.