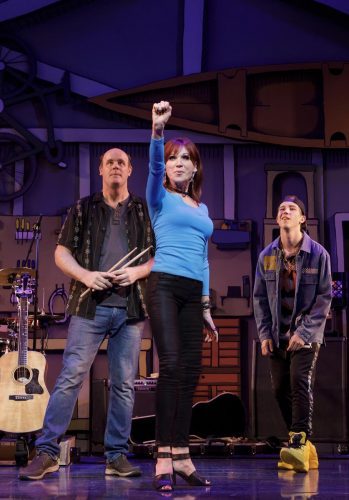

Emory (Robin De Jesús), Bernard (Michael Benjamin Washington), Larry (Andrew Rannells), and Michael (Jim Parsons) dance at birthday party that is about to become rather intense (photo by Joan Marcus)

Booth Theatre

222 West 45th St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Saturday through August 11, $69-$199

boysintheband.com

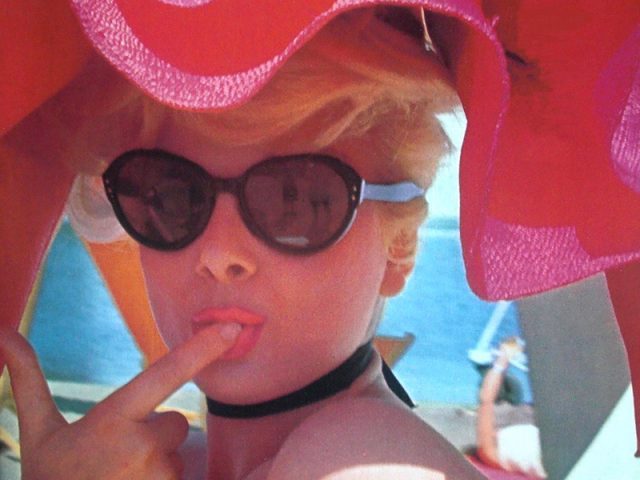

There’s quite a party going on eight times a week at the Booth Theatre, but along with all the drinking and dancing is a whole lot of internalized fear and self-loathing. Mart Crowley’s groundbreaking, controversial play, The Boys in the Band, is making its Broadway debut in a raucous fiftieth-anniversary adaptation lavishly directed by Joe Mantello. Originally presented in 1968, when it ran downtown for more than two years (totaling a thousand and one performances), the revival opened tonight at the Booth Theatre, not showing a bit of its age — aside from its rotary phones. Much has happened in the intervening half century, from the Stonewall Riots to the AIDS crisis to the legalization of same-sex marriage, but The Boys in the Band — the title comes from a line in the 1954 Judy Garland / James Mason film A Star Is Born — still is compelling, a bitter, searing look at the inner struggle many gay men experience in their life, both staying in and coming out of the closet. Over the years, the play has been accused of being hateful and mean-spirited, of spreading gay stereotypes, promoting offensive language, and hindering the advancement of homosexuals in society at large; it has also been praised for helping men come to terms with their sexual identity and to join the fight for gay rights. Frighteningly, several original cast members died of AIDS. But now, for the first time in the show’s history, every member of the cast is gay and out, in addition to Crowley, Mantello, and one of the producers, which is cause for joy all on its own, on various levels. It also helps that the show is still tantalizing and involving and packs a punch, literally as well as figuratively.

Fiftieth-anniversary production of The Boys in the Band is reason to celebrate at the Booth Theatre (photo by Joan Marcus)

The Boys in the Band takes place more or less in real time in Michael’s (Jim Parsons) lovely duplex in the East Fifties, decorated with fancy mirrors, glass walls, a central staircase, and comfy chairs and couches. (The set and costumes are by the always innovative David Zinn, with splendid lighting by Hugh Vanstone.) Michael, who is worried about his receding hairline and has recently stopped drinking, is hosting a birthday party for his best friend, the acerbic Harold (Zachary Quinto), who is turning thirty-two. Before the fête, Donald asks Michael who is coming. “I think you know everybody anyway — they’re the same old tired fairies you’ve seen around since day one. Actually, there’ll be seven, counting Harold and you and me,” Michael says. “Are you calling me a screaming queen or a tired fairy?” Donald replies. “Oh, I beg your pardon — six tired, screaming fairy queens and one anxious queer,” Michael shoots back. That language, now considered “hate speech” by millennials and others, sets the tone of much of the discourse that follows; it’s also not nearly as shocking now as it was in 1968. The invited guests are Michael’s part-time lover, the ruggedly handsome Donald (Matt Bomer); flaming queen Emory (Robin De Jesús); Michael’s good friend Larry (Andrew Rannells) and his new beau, Hank (Tuc Watkins), who has left his wife and children; and the respectable, dignified Bernard (Michael Benjamin Washington). Michael’s straight college roommate, Alan (Brian Hutchison), arrives unexpectedly from Washington, bringing his own set of heterosexual problems; also joining in the festivities is Cowboy (Charlie Carver), an adorable, if not very bright, male prostitute who is one of Harold’s gifts. As the alcohol flows and the music swirls, there’s plenty of needling and not-too-subtle flirting, but when Michael insists they all play a telephone game, things get quickly out of hand as the barbs become much more pointed and hurtful, led by Michael’s vicious mean streak. “Sounds like there’s, how you say, trouble in paradise,” Michael says about a lover’s quarrel. “If there isn’t, I think you’ll be able to stir up some,” Harold offers.

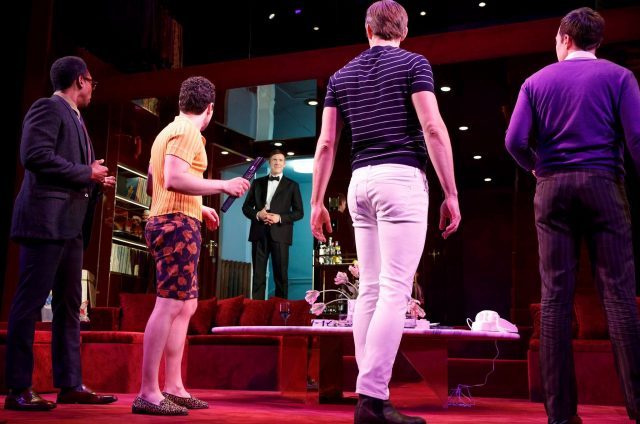

Party swiftly changes upon arrival of the straight, uninvited Alan (Brian Hutchison) (photo by Joan Marcus)

The Boys in the Band is viciously funny as it takes on gay stereotypes without exploiting them. In 2018 the effect is somewhat different from 1968 (it was also made into a film in 1970 by William Friedkin and was previously revived in New York in 1996 and 2010) in that the audience now sees characters who are gay, not gay characters, a paradigm shift in the widespread acceptance of gay culture throughout much of America, revolutionized by the gay community’s response to the vice squad raid on the Stonewall Inn in 1969, which essentially set the gay pride movement in motion. As mounted by two-time Tony winner Mantello (The Humans, Love! Valour! Compassion!) — who played Louis in the original Broadway production of Angels in America in 1993-94, the seminal “Gay Fantasia” that is currently being spectacularly revived at the Neil Simon Theatre — the show focuses on individual identity. What matters is what’s going on at the party itself, not what might be occurring outside in a world that today is more sensitive to the LGBTQ community. Instead of being stereotypes, the characters now feel more real, genuine examples of the diversity among gay men while honoring that difference. “Everybody’s just a little bit homosexual, whether they like it or not,” Allen Ginsberg sang. In The Boys in the Band, that might even extend to Alan, who is married with two kids but seems instantly attracted to Hank — perhaps primarily because he sees so much of himself in Larry’s lover.

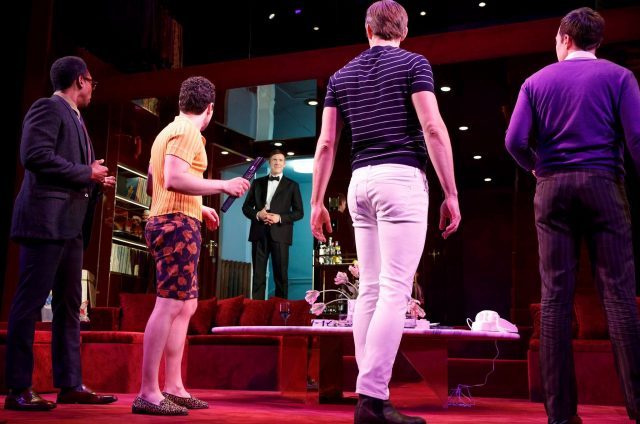

Phone-call game offers surprises galore in The Boys in the Band (photo by Joan Marcus)

All these years later, it is evident that Crowley, who wrote a sequel, The Men from the Boys, in 2002, captured more than just a moment in time; he was embracing individuality as well as the very zeitgeist of homosexuality, even as the party devolves amid the onslaught of personal demons coming to the fore. Crowley also touches on racism and anti-Semitism in addition to homophobia. When Michael is upset that Bernard allows Emory to use the N-word but not him, Bernard, the only black character, explains, “He can do it, Michael. I can do it. But you can’t do it.” That warning also serves as a clever way to take back the oft-criticized gay language in the show, telling the audience who can say what when, that gays own a specific vocabulary just as blacks do. The ensemble cast is outstanding, and judging from all the publicity the actors and crew members have been doing, they seem to be having tons of fun performing the 110-minute intermissionless play. Parsons (An Act of God, Harvey) and Hutchison (La Cage aux Folles, Mamma Mia!) are particularly effective, as their characters change the most during the party. It all might not be as radical or subversive as it once was, but this version is extremely effective in making all of us, gay or straight or trans, etc., consider how far we’ve come as a society while understanding how much more we still have to accomplish. Perhaps The Boys in the Band will be more of a dusty time-capsule piece in 2068, when it turns one hundred.