Marisa Tomei is fiery and passionate as Serafina in Roundabout revival of Tennessee Williams’s The Rose Tattoo (photo by Joan Marcus)

American Airlines Theatre

227 West 42nd St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through December 8, $59-$299

212-719-1300

www.roundabouttheatre.org

Following the disappointing reaction to his third major play, Summer and Smoke, a Broadway failure in 1948 after the runaway successes of 1944’s The Glass Menagerie and 1947’s A Streetcar Named Desire, Mississippi-born playwright Tennessee Williams headed to Sicily with the love of his life, Frank Merlo. The trip reenergized Williams and inspired him to write The Rose Tattoo, which won four Tonys in 1951, including Best Play, Best Supporting Actor (Eli Wallach), and Best Supporting Actress (Maureen Stapleton). “The Rose Tattoo was my love-play to the world,” he wrote in Memoirs. “It was permeated with the happy young love for Frankie and I dedicated the book to him, saying: ‘To Frankie in return for Sicily.’” Roundabout’s revival of the play at the American Airlines Theatre, its ninth Williams show since 1975, is a fiery, passionate affair imbued with broad comedy, along with muddling confusion.

The play is set in 1950 in a Gulf Coast village populated by Sicilian immigrants. Serafina Delle Rose (Marisa Tomei) is eagerly awaiting the return of her truck-driver husband, who she calls the Baron. “The clock is a fool. I don’t listen to it. My clock is my heart and my heart don’t say tick-tick, it says love-love!” she tells Assunta (Carolyn Mignini), an elderly fattuchiere. But the Baron never makes it home, leaving Serafina a young widow raising a daughter, Rosa (Ella Rubin), by herself. Regularly surrounded by a Greek chorus of women in black (Andréa Burns as Peppina, Susan Cella as Giuseppina, Jennifer Sánchez as Mariella, and Ellyn Marie Marsh as Violetta) and with the Strega (Constance Shulman) ever lurking about, the young widow mourns intensely for three years, praying to her very special statue of the Virgin Mary at a shrine at stage front and to the urn that holds her husband’s ashes. Serafina, a seamstress having trouble sewing her life back together, swears to be faithful to the Baron’s memory while she tries to protect Rosa’s virginity as Rosa strenuously tries to lose it to Jack (Burke Swanson), an eighteen-year-old sailor in the throes of young love. But when she overhears Bessie (Paige Gilbert) and Flora (Portia) gossiping about how the Baron cheated on her with the fancy Estelle Hoehengarten (Tina Benko), Rose has to rethink her life, especially when she meets another truck driver, Alvaro Mangiacavallo (Emun Elliott), as he’s being harassed by a racist traveling salesman (Greg Hildreth). Alvaro reminds her of the Baron, lighting a fire inside her she hasn’t felt for a long time.

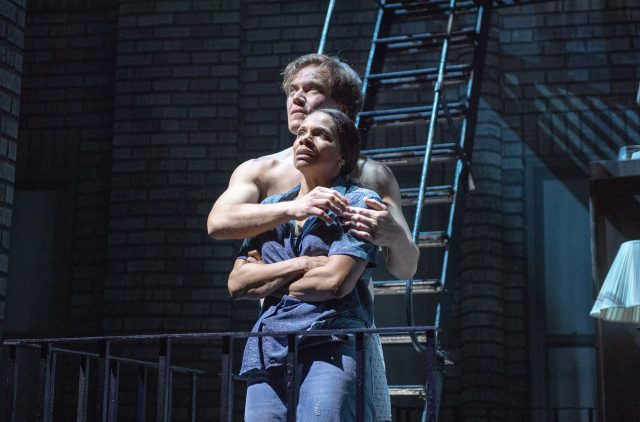

Serafina Delle Rose (Marisa Tomei) and Alvaro Mangiacavallo (Emun Elliott) find common ground in The Rose Tattoo at the American Airlines Theatre (photo by Joan Marcus)

Obie-wining director Trip Cullman zeroes in on the comic aspects of Williams’s story; if you’ve seen the 1955 movie starring Anna Magnani, who won an Oscar as Serafina, a role Williams wrote for her, you might be surprised at just how funny it is, including a bizarre moment with condoms that led to an arrest in a 1957 Irish production. Meanwhile, a scene involving Bessie and Portia coming to Serafina to pick up clothing she made for them is so racist it’s hard not to wonder why it’s done in that style in this day and age. Many of Cullman’s plays have unique and unusual sets that offer complex ways to look at the work, from Lobby Hero and Significant Other to Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow Moscow and The Pain of My Belligerence. But Mark Wendland’s stage for The Rose Tattoo is confounding. It’s a combination of indoor and outdoor spaces, with a wooden walkway over sand, a living room, a window, a flock of pink flamingos at the back, and Lucy Mackinnon’s projections of the tide rolling in on the shore on three sides. Characters enter and exit inconsistently in too many different ways so it’s hard to tell where everything leads to and from. Tomei (The Realistic Joneses, How to Transcend a Happy Marriage), whose maternal grandmother was Sicilian, is steamy and, appropriately, ardent — Serafina means “ardent” in Italian — as the zealous widow, imbuing her with a fierce sexuality, leaving Elliott (Black Watch, Red Velvet), in his Broadway debut, to play catch-up. (The pair was played by Stapleton and Wallach in the 1951 original, Magnani and Burt Lancaster in the 1955 film, Stapleton and Harry Guardino in the 1966 Broadway revival, and Mercedes Ruehl and Anthony LaPaglia in the 1995 Broadway adaptation.) Rubin is a force as Rosa, representing the next generation of Italian Americans who are not about to do things the way their parents did. Jonathan Linden contributes country-folk blues off stage right, enhancing the period setting.

“During the past two years I have been, for the first time in my life, happy and at home with someone and I think of this play as a monument to that happiness, a house built of images and words for that happiness to live in,” Williams wrote to Elia Kazan in June 1950 when asking him to direct the show. “But in that happiness there is the long, inescapable heritage of the painful and the perplexed like the dark corners of a big room.” Williams even threw in a nod to Merlo, the man responsible for his happiness and whom he called the Little Horse, by giving Alvaro the last name Mangiacavallo, which means “eat a horse.” This latest Broadway revival of The Rose Tattoo also manages to find happiness amid the painful and the perplexed.