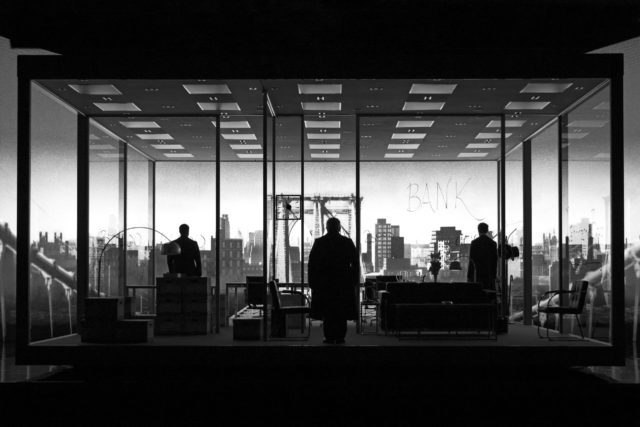

Daniel Hillard (Rob McClure) goes to extreme measures to see his kids in Mrs. Doubtfire (photo by Joan Marcus)

MRS. DOUBTFIRE

Stephen Sondheim Theatre

124 West 43rd St. between Sixth & Seventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 8, $79 – $229

mrsdoubtfirebroadway.com

Robin Williams and Stephen Sondheim must be turning over in their graves — or urns. The musical adaptation of Chris Columbus’s overrated hit 1993 movie, Mrs. Doubtfire, in which Williams plays the title character, a divorced actor who dresses up as an older Scottish nanny in order to spend more time with his children, opened earlier this month at the Stephen Sondheim Theatre on West Forty-Third St., less than two weeks after the musical genius passed away at the age of ninety-one. Williams died in 2014 at the age of sixty-three.

Mrs. Doubtfire the musical is a labored, inorganic embarrassment, a jaw-droppingly inauthentic mess that is scheduled to run for at least six months on the Great White Way. Tony nominee Rob McClure, the talented star of such duds as Chaplin and Honeymoon in Vegas, dives into the shtick headfirst, but four-time Tony-winning director Jerry Zaks is trapped by Karey Kirkpatrick and John O’Farrell’s leaden book and Karey and Wayne Kirkpatrick’s trite music and lyrics. Williams was able to make the film somewhat palatable, but McClure never has a chance with the Broadway version.

Just as the movie felt like a retread of Sydney Pollack’s 1982 romantic comedy, Tootsie, in which Dustin Hoffman plays an unemployed actor who dresses up as an unfashionable older woman in order to get a part on a soap opera, Mrs. Doubtfire the musical offers little we haven’t already seen in the 2019 musical adaptation of Tootsie, which earned ten Tony nominations, winning two awards.

Andre (J. Harrison Ghee) and Frank (Brad Oscar) preen for Wanda Sellner (Charity Angél Dawson) as Daniel (Rob McClure) looks on in Mrs. Doubtfire (photo by Joan Marcus)

Nearly every musical number feels forced and unnatural, as if Zaks (La Cage aux Folles, Hello, Dolly!), choreographer Lorin Lotarro (Waitress, Merrily We Roll Along), and the Kirkpatricks (Something Rotten!) looked around David Korins’s set to find random objects to incorporate into the dancing. When Daniel and the kids start playing air guitar with brooms, well, I considered jumping onstage and sweeping them all away, for the benefit of the audience as well as the performers. Meanwhile, the Spanish restaurant where a critical late scene occurs should be shut down for improper use and storage of musical theater.

The show is primarily set in the Hillard home, where father Daniel (McClure) has plenty of time to hang around with his three kids, Lydia (Analise Scarpaci), Christopher (Jake Ryan Flynn), and Natalie (Avery Sell). While his wife, Miranda (Jenn Gambates), is working hard, putting together a fashion line with her hunk of a partner, Stuart Dunmire (Mark Evans), Daniel is like a fourth child, running around the house with the three of them and breaking things. Lydia finally has had enough and throws him out; when the judge awards full custody to Lydia, Daniel is distraught, ready to do whatever he can to spend time with them again. He is watched closely by court liaison officer Wanda Sellner (Charity Angél Dawson), who will ultimately report back to the judge whether Daniel has an acceptable place to live and a regular job and, therefore, should be allowed to have shared custody.

But it all gets turned upside down and inside out when Daniel hatches the plan to pretend he’s Mrs. Euphegenia Doubtfire — and gets the job as his children’s nanny, taking care of them every weekday afternoon. He has to keep his secret from Lydia as well as the kids, but Wanda is on the prowl, suspicious that something nefarious is going on.

A game cast never has a chance in Mrs. Doubtfire (photo by Joan Marcus)

Brad Oscar and J. Harrison Ghee, as Daniel’s brother, Frank, and Frank’s partner, Andre, respectively, are supposed to provide comic relief (it’s already a comedy, right?) as the designers behind Daniel’s transformation into Mrs. D, but their jokes quickly become repetitive (for example, how Frank has to speak extra loudly every time he tells a lie), and laughing at flamboyant gay minor characters is not as much fun as it was once upon a time. And the scenes with Peter Bartlett as hapless kids’ show host Mr. Jolly (accompanied by Jodi Kimura as humorless channel president Janet Lundy) are not very jolly, unless you find laughing at doddering elderly men hysterical.

“What’s wrong with this picture?” the opening number prophetically asks. The show had to shut down for more than a week because of positive Covid cases; for those of you who had tickets during that time, consider yourselves lucky. [Ed. note: The musical is going on hiatus from January 10 to March 14 “out of concern for the potential long-term employment of everyone who works on Mrs. Doubtfire, and the extended run of the show.”]