Ernestine (Debra Messing) lives a relatively simple life in Noah Haidle’s Birthday Candles (photo by Joan Marcus)

BIRTHDAY CANDLES

American Airlines Theatre

227 West 42nd St. between Broadway & Eighth Ave.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 29, $39-$250

212-719-1300

www.roundabouttheatre.org

“Have I wasted my life?” Ernestine (Debra Messing) asks her mother, Alice (Susannah Flood), at the beginning of Noah Haidle’s Birthday Candles, continuing through May 29 at the Roundabout’s American Airlines Theatre.

Haidle’s Broadway debut is a touching and bittersweet, if at times Hallmark-y, look at ninety years in the life of an average American woman in Grand Rapids, Michigan. The play is built around her annual preparation of her birthday cake, a recipe handed down from mother to daughter in their family. Each scene takes place in the same kitchen, which never changes. Ernestine wears essentially the same costume (by Toni-Leslie James) in every scene as she ages, the time shifts indicated only by a sharp chime that arrives in the middle of the action and contextual clues given by the dialogue and the outfits of the other characters, which range from her boyfriend and future husband, Matt (Tony nominee John Earl Jelks), to her numbers-obsessed neighbor, Kenneth (Enrico Colantoni), who has a serious crush on her, to a parade of children, their spouses, their children, etc. (Jelks, Crystal Finn, Susannah Flood, and Christopher Livingston play multiple roles, their character not always immediately apparent as the next generation arrives. I saw understudy Brandon J. Pierce stepping in for Livingston.)

Ernestine serves as a witness to birth and death, illness and infidelity, success and failure, devoid of any references to the outside world. Whereas Jack Crabb, portrayed by Dustin Hoffman in Arthur Penn’s 1970 epic revisionist Western Little Big Man, spends his 121-year life on the road, meeting famous people (General Custer, Wild Bill Hickok), encountering a diverse series of events (battles with Native Americans, saloon shootouts, getting married and operating a small store), and watching everything change around him, Ernestine lives in a self-contained bubble, with no inkling of what is happening in society at large; there are no references to politics, sports, entertainment, anything that can put us in a specific time and place, only what is occurring within the family at any given moment, and always on her birthday. Another signifier is Ernestine’s annual measurements penciled on a doorframe; she grows taller until she begins shrinking as an old woman. Birthday Candles also recalls Thornton Wilder’s 1931 The Long Christmas Dinner, a one-act play that covers ninety years of the Bayard clan without ever leaving the dining room.

The show opens as Ernestine is turning seventeen, filled with the excitement of all that life offers. “I am a rebel against the universe. I will wage war with the everyday. I am going to surprise God!” she announces to her mother, who is more concerned with teaching her daughter the basic but cherished recipe for the cake.

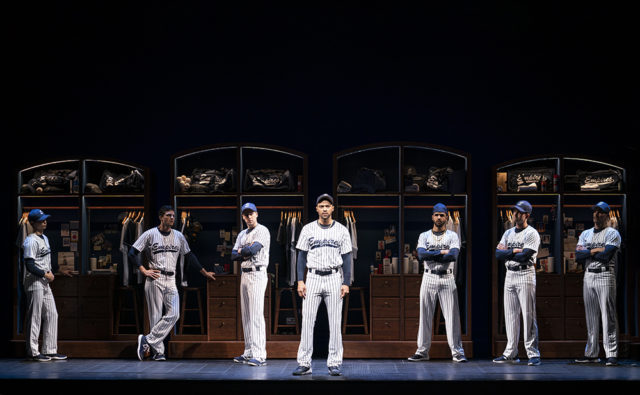

Ninety years pass by in ninety minutes in Birthday Candles (photo by Joan Marcus)

“Eggs, butter, sugar, salt. The humblest ingredients,” Alice tells Ernestine. “But when you turn back and look far enough, you see atoms left over from creation,” implying that the history of the family — perhaps of humanity itself — is embodied in the cake.

Ernestine responds, “Stardust. The machinery of the cosmos is all here, I get it. Will you help me with my audition?”

Ernestine is practicing for the lead in her high school’s gender-switching production of Queen Lear, signaling that Birthday Candles is going to be a matriarchal tale about mothers and children; the men play second fiddle. “Madam, do you know me?” Alice reads as Cordelia. Ernestine, as the queen, answers, “You are a spirit, I know. When did you die?” In King Lear, the elderly monarch starts losing his mind as he deals with his three daughters, the calculating Regan and Goneril and the youngest, Cordelia, the only one who truly loves him. By having Alice reading the part of Cordelia and Ernestine portraying Lear, Haidle is alerting us to the casting choices and plot that follow.

As time marches on, new characters enter and old characters depart, the future replacing the past. Jelks portrays Ernestine’s husband, Matt, and their son, Billy; Finn is Billy’s wife, Joan, and their daughter, Alex; and Flood is Ernestine’s mother, Ernestine’s daughter, Madeline, and Alex’s daughter, Ernie. Finn and Livingston also appear as a surprise couple. People discuss their jobs, their relationships, and their personal identities in a vacuum. At one point, Madeline tells her parents and brother, “I don’t have a definition anymore. There aren’t any. In me. Or in the world.”

The actors make only small adjustments as their characters age, except for Messing once she passes her real-life age of fifty-three. Her slow decline as she survives so many of the others is heartbreaking, but she’s not about to stop making that cake on her birthday, no matter how old she is or who is around to enjoy it with her.

Ernestine’s (Debra Messing) life flashes before our eyes in Noah Haidle’s Broadway debut (photo by Joan Marcus)

One who is always there with her is her pet goldfish, given to her by Kenneth when they were seventeen and named Atman, the Sanskrit word for an individual’s essence, or soul. Kenneth explains, “The Katha Upanishad is the first to use the concept of Atman as a beginning argument of achieving liberation from human suffering. I quote, and please forgive my basic translation. ‘Like fire spreads itself throughout the world and takes the shape of that which it burns, the internal Atman of all living beings, while remaining one fire, takes the form of what He enters and is at the same time outside all forms.’” He points out that goldfish have only three-second memories and “then the world begins anew.” That’s one way to forget the pain, although the pleasurable moments vanish as well; Ernestine’s life is filled with plenty of both.

Haidle (Vigils, Smokefall) has created an emotional, gripping tale that is haunted by the fear of death as it explores various concepts of love, between married couples, parents and children, siblings, owners and pets, and a devoted neighbor. Director Vivienne Benesch, who helmed the play’s world premiere at the Detroit Public in 2017, manages the time shifts with aplomb as characters come and go through several open doorways on Christine Jones’s welcoming kitchen set, over which hangs dozens of household objects — remnants of a long life — in addition to the phases of the moon, a reminder of time itself.

Emmy winner Messing (Will & Grace,Outside Mullingar) is enthralling as Ernestine, who could be any of us. The different paths her life takes, each twist and turn, lead to familiar small dramas that are fully relatable; as she ages, it is hard not to consider what your own future holds. I am not a crier, but I have to admit that I was wiping away tears in the final scenes, and I was not the only one.

Colantoni (The Distance from Here, Fear) is utterly charming in his Broadway debut as Kenneth, an oddball who spends more than half a century pining for Ernestine, a regular reminder of the things in life we want that are so close but can so often be just out of reach. The rest of the cast is excellent as well, with a memorable comic turn by Finn as Joan, who has no filter and talks to herself out loud.

At a 1974 press conference, Muhammad Ali said, “If a man looks at the world when he is fifty the same way he looked at it when he was twenty and it hasn’t changed, then he has wasted thirty years of his life.” Did Ernestine waste her life? It’s a question we all ask ourselves as our birthdays come and go.