Lillie P. Bliss, seen here in a photo circa 1924, is subject of new MoMA exhibit (the Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York)

LILLIE P. BLISS AND THE BIRTH OF THE MODERN

MoMA, the Museum of Modern Art

11 West Fifty-Third St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Through March 29, $17-$30

www.moma.org

“Dear Miss Bliss,” Bryson Burroughs, curator of paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, began in a letter to Lillie Plummer Bliss upon her crucial support of the 1921 “Loan Exhibition of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Art,” “I salute you as a benefactress of the human race!”

Born in Boston in 1864, Bliss cofounded the Museum of Modern Art in 1929 with Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and Mary Quinn Sullivan. She died in New York two years later, leaving her collection of approximately 120 works by late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century French artists to the institution, including paintings by Paul Cezanne, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Georges Seurat, and Odilon Redon. She also encouraged the museum to sell pieces of her bequest as necessary to acquire other works, which led the museum to expand its collection with such masterpieces as Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night.

Bliss is celebrated in the lovely MoMA exhibit “Lillie P. Bliss and the Birth of the Modern,” continuing through March 29. Organized by Ann Temkin and Romy Silver-Kohn, the show features such works as Cezanne’s The Bather, Seurat’s At the Concert Européen (Au Concert Européen), Marie Laurencin’s Girl’s Head, Amedeo Modigliani’s Anna Zborowska, Picasso’s Woman in White, and Henri Matisse’s Interior with a Violin Case.

The centerpiece is The Starry Night, which, if you’re lucky, you will get to experience on your own, as it’s hanging in a different spot from its usual place, free of the usual mass of people in front of it, taking photos and videos, obstructing one another’s clear views and peaceful contemplation of one of the most famous canvases in the world.

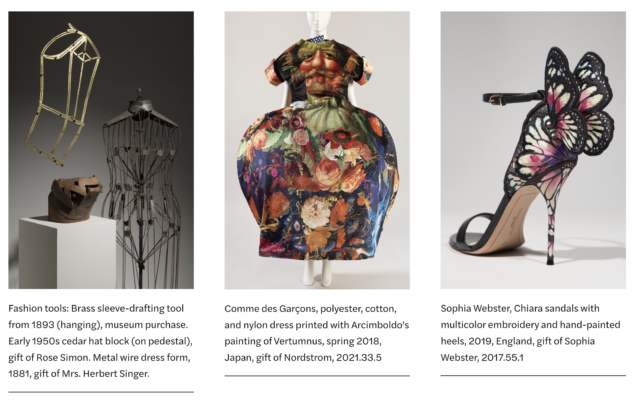

Installation view, “Lillie P. Bliss and the Birth of the Modern” (photo by Emile Askey)

The show is supplemented with such ephemera as old catalogs, acquisition notices, pages from scrapbooks, photos of Bliss as a child, and a few rare letters, as Bliss requested that all her personal papers be destroyed shortly before her death in 1931 at the age of sixty-six. One key letter she sent to a National Academician is quoted in the MoMA book Inventing the Modern: Untold Stories of the Women Who Shaped The Museum of Modern Art, in which Bliss writes: “We are not so far apart as you seem to think in our ideas on art, for I yield to no one in my love, reverence, and admiration for the beautiful things which have already been created in painting, sculpture, and music. But you are an artist, absorbed in your own production, with scant leisure and inclination to examine patiently and judge fairly the work of the hosts of revolutionists, innovators, and modernists in this widespread movement through the whole domain of art or to discriminate between what is false and bad and what is sometimes crude, perhaps, but full of power and promise for the enrichment of the art which the majority of them serve with a devotion as pure and honest as your own. There are not yet many great men among them, but great men are scarce — even among academicians. The truth is you older men seem intolerant and supercilious, a state of mind incomprehensible to a philosopher who looks on and enjoys watching for and finding the new men in music, painting, and literature who have something to say worth saying and claim for themselves only the freedom to express it in their own way.”

Bliss did it her own way as well.

Clarence H. White, Belle da Costa Greene, platinum print, 1911 (courtesy the Clarence H. White Collection)

BELLE DA COSTA GREENE: A LIBRARIAN’S LEGACY

Morgan Library & Museum

225 Madison Ave. at 36th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 4, $13-$25

www.themorgan.org

“My friends in England suggest that I be called ‘Keeper of Printed Books and Manuscripts,’” Belle da Costa Greene told the New York Times in 1912. “But you know they have such long titles in London. I’m simply a librarian.”

Born Belle Marion Greener in 1879 in Washington, DC, Greene became the first director of the Morgan Library, specializing in the acquisition of rare books and manuscripts, a Black woman passing for white in a field dominated by men. Prior to her death in New York City in 1950 at the age of seventy, she destroyed all her diaries and private papers, but her correspondence with others paints a picture of an extraordinary woman breaking barriers personally and professionally as she came to be known as “the soul of the Morgan Library.”

Curated by Philip S. Palmer and Erica Ciallela, “Belle da Costa Greene: A Librarian’s Legacy” consists of nearly two hundred items, from letters, photographs, yearbooks, and board minutes to illuminated manuscripts, jewelry, furniture, and books by Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, William Butler Yeats, and Dante Alighieri in addition to canvases by Archibald J. Motley Jr., Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn, Ḥabīb-Allāh Mashhadī, Albrecht Dürer, Henri Matisse, Jacques Louis David, and Thomas Gainsborough. Greene’s early holy grail was Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur; she was prepared to pay up to $100,000 for the work, printed by William Caxton in 1485, but won it for $42,000 at a 1911 auction.

Re-creation of Belle da Costa Greene’s office is centerpiece of Morgan exhibit (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

Just as MoMA would not be what it is today without Lillie P. Bliss, the Morgan would not be the same without Greene. While at Princeton, she became friends with Morgan’s nephew Junius Spencer Morgan, who collected rare books and who recommended Greene to his uncle; J. P. Morgan hired her as a librarian in 1905, and she was appointed director in 1924. Her starting salary was $75 a month, but she was earning $10,000 a year by 1911.

The show is divided into sixteen sections, from “A Family Identity,” “An Empowering Education,” and “Questioning the Color Line” to “A Life of Her Own: Collector and Socialite,” “A Life of Her Own: Philanthropy and Politics,” and “Black Librarianship.” It details Greene’s childhood, her successful parents, her education, and her friendship with art historians Bernard and Mary Berenson; Greene had a long-term affair with Bernard, who had an open marriage with his wife. Following Morgan’s death in 1913, Greene worked closely with J.P.’s son, Jack, to expand the institution’s holdings. The centerpiece is a re-creation of Greene’s office, with her desk, swivel chair, and card catalog cabinet, all made by Cowtan & Sons, accompanied by a quote from a letter she wrote to Bernard in 1909: “I was busily engaged hunting up particulars of a certain book & half the Library was on my desk.”

One of the most heart-wrenching parts of the exhibit explores her relationship with her nephew and adopted son, Robert MacKenzie Leveridge, who died tragically in WWII.

The Morgan show is supplemented by three online sites that offer further information about Greene’s life and career: “Telling the Story of Belle da Costa Greene,” “Belle da Costa Greene and the Women of the Morgan,” and “Belle da Costa Greene’s Letters to Bernard Berenson.”

At the heart of it all is Greene’s dedication to her work. As she also told the Times in 1912, “I just have to accomplish what I set out to do, regardless of who or what is in my way.”

Like Bliss, Greene accomplished all that and more, in her own way.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]