Who: Steve Earle

What: Annual Winter Residency

Where: City Winery, 155 Varick St. between Spring & Vandam Sts., 212-608-0555

When: Monday, January 5, 12, 19, 26, $45-$75, 8:00

Why: Folk-rock troubadour Steve Earle, whose next album with the Dukes, Terraplane, comes out on February 17, teams up with special guests every Monday in January at City Winery, beginning with Willie Watson on January 5, followed by Shawn Colvin and Kate Davis on January 12, Willie Mason on January 19, and Willie Nile on January 26

twi-ny recommended events

BIRDMAN OR (THE UNEXPECTED VIRTUE OF IGNORANCE)

Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) and Mike Shiner (Edward Norton) battle it out onstage and off in BIRDMAN

BIRDMAN OR (THE UNEXPECTED VIRTUE OF IGNORANCE) (Alejandro G. Iñárritu, 2014)

Opened October 17

www.birdmanthemovie.com

In Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s swirling camera immerses the audience in Mexican director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s gripping whirlwind black comedy of a former superhero action star trying to regain respect on the Broadway stage. Onetime Batman star Michael Keaton plays Riggan Thomson, an actor who left his blockbuster Birdman franchise in order to be taken more seriously. Twenty years later, he is considering refinancing his house in order to support his Broadway debut as writer, director, and star of an adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.” As he works on the play with costars Mike Shiner (Edward Norton), Shiner’s girlfriend, Lesley (Naomi Watts), and his own girlfriend, Laura (Andrea Riseborough), he battles his inner demons, which take the form of the dark, gravelly voice of his Birdman character (voiced by Keaton). Either his somewhat obscure but vaguely Buddhist spiritual pursuits or his Birdman abilities also apparently give him the ability to move objects with his mind; the first time we see him, he is levitating in front of the window of his dressing room at the St. James Theatre. His team also includes his devoted lawyer, producer, and best friend, Jake (Zach Galifianakis), his stalwart stage manager, Annie (Merritt Wever), and his daughter and personal assistant, Sam (Emma Stone), a bitter and cynical young woman fresh out of rehab. He also has an encounter with vicious theater critic Tabitha Dickinson (Lindsay Duncan), who is licking her lips in anticipation of reviewing his show. With opening night approaching, Thomson must look deep within himself as he reevaluates his life and career.

In Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Ignorance), Oscar-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki’s swirling camera immerses the audience in Mexican director Alejandro G. Iñárritu’s gripping whirlwind black comedy of a former superhero action star trying to regain respect on the Broadway stage. Onetime Batman star Michael Keaton plays Riggan Thomson, an actor who left his blockbuster Birdman franchise in order to be taken more seriously. Twenty years later, he is considering refinancing his house in order to support his Broadway debut as writer, director, and star of an adaptation of Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.” As he works on the play with costars Mike Shiner (Edward Norton), Shiner’s girlfriend, Lesley (Naomi Watts), and his own girlfriend, Laura (Andrea Riseborough), he battles his inner demons, which take the form of the dark, gravelly voice of his Birdman character (voiced by Keaton). Either his somewhat obscure but vaguely Buddhist spiritual pursuits or his Birdman abilities also apparently give him the ability to move objects with his mind; the first time we see him, he is levitating in front of the window of his dressing room at the St. James Theatre. His team also includes his devoted lawyer, producer, and best friend, Jake (Zach Galifianakis), his stalwart stage manager, Annie (Merritt Wever), and his daughter and personal assistant, Sam (Emma Stone), a bitter and cynical young woman fresh out of rehab. He also has an encounter with vicious theater critic Tabitha Dickinson (Lindsay Duncan), who is licking her lips in anticipation of reviewing his show. With opening night approaching, Thomson must look deep within himself as he reevaluates his life and career.

Riggan Thomson (Michael Keaton) tries to reestablish his relationship with his daughter, Sam (Emma Stone), in BIRDMAN

Iñárritu (Amores Perros, Babel) and Lubezki (Gravity, Children of Men) take viewers on a wicked, wild ride in Birdman, which is masterfully made to look as if it is one continuous two-hour shot, the handful of cuts cleverly hidden as the camera roams through the narrow hallways and small dressing rooms of the St. James and into (and above) Times Square, instilling the film with the energy and feel of live theater. The live aspect reaches a new peak when, as Thomson is winding his way backstage accompanied by Antonio Sánchez’s propulsive percussion score, he runs past a man playing the music on the drums. (Think Count Basie leading his band out on the western plains in Blazing Saddles.) Another inside joke occurs when Shiner is shown reading Jorge Luis Borges’s Labyrinths, a short-story collection filled with magical scenes of its own. Keaton gives the best, bravest performance of his career as Thomson, a comeback role that clearly hits home; it seems so tailor made for him that it is hard to believe it was not written specifically for the ’80s star of such hits as Night Shift, Mr. Mom, Gung Ho, and Beetlejuice. Keaton — who has had very limited theater experience — lets it all hang out, as does Norton, channeling his narrator character from Fight Club. The film’s supporting cast is outstanding as well, including Watts, who is now considering making her long-awaited theater debut, and Amy Ryan as Thomson’s ex-wife, but Stone’s big, expressive eyes nearly steal the movie. Birdman is so fresh and potent, so dynamic and spirited, that it’s easy to forgive it its few plot holes. It’s a biting satire of Hollywood and Broadway, of fame and stardom, a magical fantasy that relates to everyone’s fear of becoming insignificant.

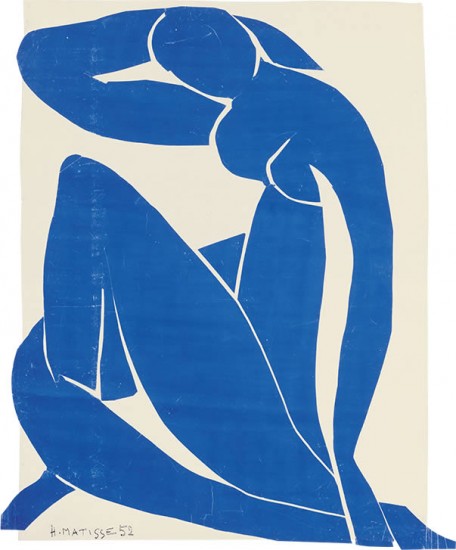

HENRI MATISSE: THE CUT-OUTS

Henri Matisse, “Blue Nude,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on canvas, spring 1952 (Musée national d’art moderne/Centre de création industrielle, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris)

Museum of Modern Art

The Joan and Preston Robert Tisch Exhibition Gallery, sixth floor

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Timed tickets daily through February 10, $25

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

Near the center of “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” visitors gather to watch excerpts from Frédéric Rossif’s 1950 Matisse film, which show the white-bearded artist at work, creating masterpieces with only painted paper and a pair of scissors. There’s a smile on everyone’s face as the eighty-year-old Matisse cuts shapes out of yellow paper, perhaps a bit more sophisticated than a young child making a row of paper dolls. And that gets right to the heart of why the exhibition is so successful, and why Matisse’s cut-outs are so beloved: It seems so simple, something that anyone can do, but of course that is not quite true, as no one has ever used a pair of scissors quite like Matisse did. In her catalog essay “Bodies and Waves,” Jodi Hauptman discusses Matisse’s methods when beginning his first “Blue Nude.” She writes, “The process was arduous. Matisse labored for a number of weeks, relentlessly revising. His studio assistant at the time, Paule Martin, pushed by Matisse to work with equal rigor, describes the tense conditions: ‘Whereas subsequent forms were cut in a single movement, the first figure demanded such patience and attention on Matisse’s part, but also from me, that it exhausted me and I was on the brink of collapse. He made me pin tiny squares of paper to enhance the curvature of the thigh or some other part of the body, then remove parts of the figure to remove colour strips, then set it back in place as my febrile fingers fumbled with the pins.’ These enhancements and removals along with markings in chalk can be seen in a series of black and white photographs made by [secretary and studio assistant] Lydia Delectorskaya to document each stage, reminding the artist where he was and where he had been in order for him to decide where to go next.” The process was so organic that Matisse used pins to place the cut-outs on the walls of his studio, moving them around in different configurations until he was ready to mount them on canvas; if you look close enough, you can still see the pinholes on these marvelous works, not quite like a child pinning them onto a board in a classroom.

Installation view, “Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs,” with (from left) “Black Leaf on Green Background,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, 1952; “Christmas Eve,” maquette for stained-glass window, gouache on paper, cut and pasted, mounted on board, 1952; “Black Leaf on Red Background,” gouache on paper, cut and pasted, 1952; and “Christmas Eve,” stained glass, summer-fall 1952 (photo by Jonathan Muzikar © 2014 the Museum of Modern Art)

“Matisse: The Cut-Outs” consists of some 170 cut-outs, drawings, maquettes, stained glass, photographs, screenprints, illustrated books, and other ephemera related to Matisse’s use of cut paper painted over with gouache, which he began in the 1930s but became his preferred medium in the mid-to-late-1940s. This creative resurgence resulted in glorious works that combine a childlike innocence with a complex mastery of space, light, shape, and color, melding abstraction with imagery of the natural world. In “Icarus,” a maquette for the 1947 book Jazz, a silhouetted figure with a red heart floats among yellow stars. (“You have no idea how, during the cut-out paper period, the sensation of flight which emanated from me helped me better to adjust my hand when it used the scissors,” Matisse said. “It’s a kind of linear and graphic equivalence to the sensation of flight.”) Leaflike images come alive in “White Alga on Red and Green Background,” “Two Masks (The Tomato),” and “Composition with Red Cross.” A somewhat figurative element is added in “Black Boxer,” a black image over a red rectangle on a green background. Matisse displays a more spiritual side in his maquettes, studies, and trials for stained-glass windows for the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence. His four blue nudes, dating from spring 1952, are simply breathtaking, as blue geometric shapes and white spaces come together to form seated figures with slightly different body positions like a contemplative four-part dance. That summer, Matisse made the nine-panel room installation “The Swimming Pool,” an extraordinary horizontal swirl about which he said, “I have always adored the sea and now that I can no longer go for a swim, I have surrounded myself with it.” It was MoMA’s conservation of the piece that led to the idea of staging the cut-out exhibition in the first place, so now the work surrounds visitors from around the world.

An April 15, 1950, black-and-white photograph by Walter Carone shows Matisse in his bed, using a long pole to draw on the wall of his room at the Hôtel Régina in Nice with charcoal. The wall already includes elements that would become “The Thousand and One Nights.” It’s a charming photo of the artist, apparently relaxing in bed while continuing to work. Of course, just as the cut-outs themselves are not simple, neither were Matisse’s last years, much of which was spent in bed and in his wheelchair. The catalog essay “The Studio as Site and Subject” notes, “In a 1952 interview with the writer André Verdet, Henri Matisse describes a cluster of colourful cut-paper forms pinned to his studio walls as a ‘little garden.’ ‘You see,’ he explains, ‘as I am obliged to remain often in bed because of the state of my health, I have made a little garden all around me where I can walk . . . There are leaves, fruits, a bird.’ As Matisse speaks, he points to ‘a large mural composition of cut paper that encompassed half the room.’” The artist is referring to pieces that he would use to create “The Parakeet and the Mermaid,” but he could just as well be describing what visitors experience as they walk through this magical exhibition, like meandering through a colorful garden filled with joy and beauty. “Matisse: The Cut-Outs” is a revelatory show, the happiest of the season, displaying a childlike wonder as experienced by an aging yet still determined artist of extraordinary talent.

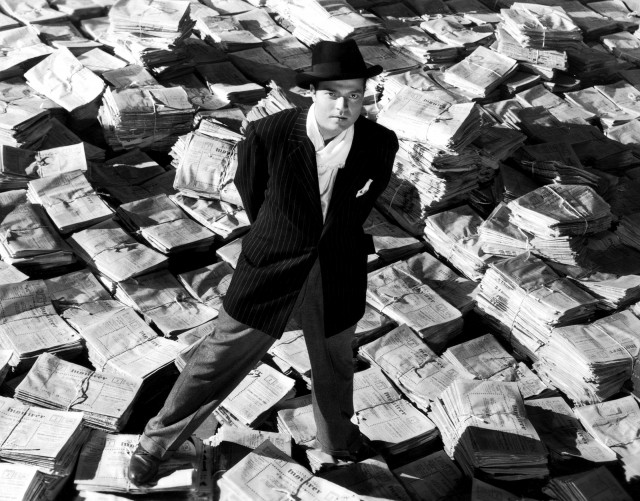

ORSON WELLES 100: CITIZEN KANE

CITIZEN KANE (Orson Welles, 1941)

Film Forum

209 West Houston St.

January 1-8

Series continues through February 3

212-727-8110

www.filmforum.org

www2.warnerbros.com

Film Forum is ringing in 2015 with the greatest American movie ever made, the epic Citizen Kane, kicking off a massive centennial celebration of the birth of its creator, the rather iconoclastic writer, director, producer, actor, and wine spokesman Orson Welles. In 1941, a young, brash, determined Welles shocked Hollywood with a masterpiece unlike anything seen before or since — a beautifully woven complex narrative with a stunning visual style (compliments of director of photography Gregg Toland) and a fabulous cast of veterans from his Mercury radio days, including Everett Sloane, Joseph Cotten, Ray Collins, Paul Stewart, and Agnes Moorehead. Each moment in the film is unforgettable, not a word or shot out of place as Welles details the rise and fall of a self-obsessed media mogul. The film is prophetic in many ways; at one point Kane utters, “The news goes on for twenty-four hours a day,” foreseeing today’s 24/7 news overload. And it doesn’t matter if you’ve never seen it and you know what Rosebud refers to; the film is about a whole lot more than just that minor mystery. Like every film the Wisconsin-born Welles made, Citizen Kane was fraught with controversy, not the least of which was a very unhappy William Randolph Hearst seeking to destroy the negative of a film he thought ridiculed him. Kane won only one Oscar, for writing — which also resulted in controversy when Herman J. Mankiewicz claimed that he was the primary scribe, not Welles. The film lost the Academy Award for Best Picture to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley, but it has topped nearly every greatest-films-of-all-time list ever since.

Film Forum is ringing in 2015 with the greatest American movie ever made, the epic Citizen Kane, kicking off a massive centennial celebration of the birth of its creator, the rather iconoclastic writer, director, producer, actor, and wine spokesman Orson Welles. In 1941, a young, brash, determined Welles shocked Hollywood with a masterpiece unlike anything seen before or since — a beautifully woven complex narrative with a stunning visual style (compliments of director of photography Gregg Toland) and a fabulous cast of veterans from his Mercury radio days, including Everett Sloane, Joseph Cotten, Ray Collins, Paul Stewart, and Agnes Moorehead. Each moment in the film is unforgettable, not a word or shot out of place as Welles details the rise and fall of a self-obsessed media mogul. The film is prophetic in many ways; at one point Kane utters, “The news goes on for twenty-four hours a day,” foreseeing today’s 24/7 news overload. And it doesn’t matter if you’ve never seen it and you know what Rosebud refers to; the film is about a whole lot more than just that minor mystery. Like every film the Wisconsin-born Welles made, Citizen Kane was fraught with controversy, not the least of which was a very unhappy William Randolph Hearst seeking to destroy the negative of a film he thought ridiculed him. Kane won only one Oscar, for writing — which also resulted in controversy when Herman J. Mankiewicz claimed that he was the primary scribe, not Welles. The film lost the Academy Award for Best Picture to John Ford’s How Green Was My Valley, but it has topped nearly every greatest-films-of-all-time list ever since.

A classic American story that never gets old, Citizen Kane, in a 4K restoration, will run at Film Forum January 1-8, igniting “Orson Welles 100,” a four-week festival programmed by Bruce Goldstein along with consultant Joseph McBride, author of What Ever Happened to Orson Welles? A Portrait of an Independent Career. Welles’s career was fraught with controversy, with battles over editorial control, finances, and politics, with more unfinished projects than completed ones. As McBride points out at the start of his 2006 book, “‘God, how they’ll love me when I’m dead!’ Welles was fond of saying in his later years, with a mixture of bitterness and ironic detachment. But that’s a half-truth at best. More than two decades after Welles’s death, his career is, in a very real sense, still flourishing. But it is a disturbing irony that Welles is more ‘bankable’ now than when he was living.” The Film Forum series confirms this statement, consisting of more than thirty films that Welles directed and/or appeared in, including multiple versions of Touch of Evil and Macbeth; the lineup ranges from the familiar (The Magnificent Ambersons, The Third Man, Compulsion, A Man for All Seasons) to the obscure (Prince of Foxes, The Black Rose, Man in the Shadow, Black Magic), from the Shakespearean (Chimes at Midnight, Macbeth, Othello) to the Muppets (The Muppet Movie). Among the double features are The Immortal Story and F for Fake, The Stranger and Journey into Fear, and Jane Eyre and Tomorrow Is Forever. McBride will be on hand to present the rarities collection “Wellesiana” as well as the “Preview version” of Touch of Evil on January 14 and the “Scottish version” of Macbeth on January 16, joined by Welles’s daughter Chris Welles Feder.

LIVE WEBCAST OF TIMES SQUARE NEW YEAR’S EVE CELEBRATION

Who: Times Square Alliance and Countdown Entertainment

What: Six-hour commercial-free live webcast, preceded by highlights from last year’s celebration

Where: Times Square

When: Wednesday, December 31, free, 6:00 pm – 12:15 am

Why: Annual New Year’s Eve celebration in the Crossroads of the World, beginning with the ball raising at 6:00, behind-the scenes stories, live performances by O.A.R., American Authors, Alejandra Guzmán, and Jencarlos Canela, a military salute by the USO Show Troupe, and more, hosted by Allison Hagendorf with correspondents Maggie Rulli, Andrea Boehlke, and Jeremy Hassell, and celebrity guests, concluding with Waterford Crystal ball drop at midnight

THE CONTENDERS 2014: THE MISSING PICTURE

THE MISSING PICTURE (L’IMAGE MANQUANTE) (Rithy Panh, 2013)

MoMA Film, Museum of Modern Art

11 West 53rd St. between Fifth & Sixth Aves.

Saturday, January 3, 7:30

Series runs through January 16

Tickets: $12, in person only, may be applied to museum admission within thirty days, same-day screenings free with museum admission, available at Film and Media Desk beginning at 9:30 am

212-708-9400

www.moma.org

www.themissingpicture.bophana.org

Winner of the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes and nominated last year for a Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award, Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture is a brilliantly rendered look back at the director’s childhood in Cambodia just as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge began their reign of terror in the mid-1970s. “I seek my childhood like a lost picture, or rather it seeks me,” narrator Randal Douc says in French, reciting darkly poetic and intimately personal text written by author Christophe Bataille (Annam) based on Panh’s life. Born in Phnom Penh in 1964, Panh, who has made such previous documentaries about his native country as S21, The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine and Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell and wrote the 2012 book L’élimination with Bataille, was faced with a major challenge in telling his story; although he found remarkable archival footage of the communist Angkar regime, there are precious few photographs or home movies of his family and the community where he grew up. So he had sculptor Sarith Mang hand-carve and paint wooden figurines that Panh placed in dioramas to detail what happened to his friends, relatives, and neighbors. Panh’s camera hovers over and zooms into the dioramas, bringing these people, who exist primarily only in memory, to vivid life. When people disappear, Panh depicts their carved representatives flying through the sky, as if finally achieving freedom amid all the horrors. He delves into the Angkar’s propaganda movement and sloganeering — the “great leap forward,” spread through film and other methods — as the rulers sent young men and women into forced labor camps. “With film too, the harvests are glorious,” Douc states as women are shown, in black-and-white, working in the fields. “There is grain. There are the calm, determined faces. Like a painting. A poem. At last I see the Revolution they so promised us. It exists only on film.” It’s a stark comparison to cinematographer Prum Mésa’s modern-day shots of the wind blowing through lush green fields, devoid of people.

Winner of the Un Certain Regard prize at Cannes and nominated last year for a Best Foreign Language Film Academy Award, Rithy Panh’s The Missing Picture is a brilliantly rendered look back at the director’s childhood in Cambodia just as Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge began their reign of terror in the mid-1970s. “I seek my childhood like a lost picture, or rather it seeks me,” narrator Randal Douc says in French, reciting darkly poetic and intimately personal text written by author Christophe Bataille (Annam) based on Panh’s life. Born in Phnom Penh in 1964, Panh, who has made such previous documentaries about his native country as S21, The Khmer Rouge Killing Machine and Duch, Master of the Forges of Hell and wrote the 2012 book L’élimination with Bataille, was faced with a major challenge in telling his story; although he found remarkable archival footage of the communist Angkar regime, there are precious few photographs or home movies of his family and the community where he grew up. So he had sculptor Sarith Mang hand-carve and paint wooden figurines that Panh placed in dioramas to detail what happened to his friends, relatives, and neighbors. Panh’s camera hovers over and zooms into the dioramas, bringing these people, who exist primarily only in memory, to vivid life. When people disappear, Panh depicts their carved representatives flying through the sky, as if finally achieving freedom amid all the horrors. He delves into the Angkar’s propaganda movement and sloganeering — the “great leap forward,” spread through film and other methods — as the rulers sent young men and women into forced labor camps. “With film too, the harvests are glorious,” Douc states as women are shown, in black-and-white, working in the fields. “There is grain. There are the calm, determined faces. Like a painting. A poem. At last I see the Revolution they so promised us. It exists only on film.” It’s a stark comparison to cinematographer Prum Mésa’s modern-day shots of the wind blowing through lush green fields, devoid of people.

The Missing Picture is an extraordinarily poignant memoir that uses the director’s personal tale as a microcosm for what happened in Cambodia during the 1970s, employing the figures and dioramas to compensate for “the missing pictures.” Like such other documentaries as Jessica Wu’s Protagonist and In the Realms of the Unreal, Michel Gondry’s Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?, Jeff Malmberg’s Marwencol, and Zachary Heinzerling’s Cutie and the Boxer, which incorporate animation, puppetry, and/or miniatures to enhance the narrative or fill in gaps, Panh makes creative use of an unexpected artistic technique, this time concentrating on painful history as well as personal and collective memory. The Missing Picture is screening January 3 at 7:30 as part of MoMA’s annual series “The Contenders,” which consists of films the institution believes will stand the test of time; the series continues with such other documentaries as Laura Poitras’s Citizenfour, Frederick Wiseman’s National Gallery, and Sergey Loznitsa’s Maidan.

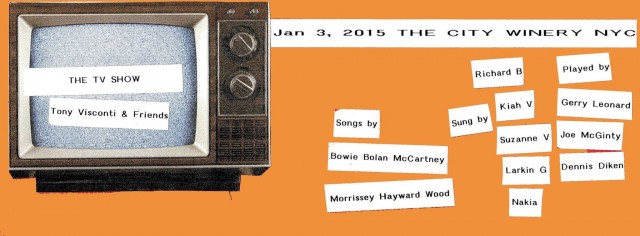

THE TV SHOW: TONY VISCONTI & FRIENDS

Who: Uber-producer, musician, and singer Tony Visconti (T Rex, David Bowie, Thin Lizzy, the Moody Blues, Adam Ant, Morrissey, Kristeen Young, etc.)

What: The TV Show

Where: City Winery, 155 Varick St. between Spring & Vandam Sts., 212-608-0555

When: Saturday, January 3, $30-$42, 8:00, followed by meet and greet, $45, 10:00

Why: Super-producer Tony Visconti takes the stage at City Winery, playing bass with Gerry Leonard on guitar, Joe McGinty on keyboards, Dennis Diken on drums, and Everett Bradley on vocals, joined by special guests Richard Barone, Suzanne Vega, Kiah Victoria, Larkin Grimm, Nakia, and others performing songs by Paul McCartney, David Bowie, Marc Bolan, Morrissey, Justin Hayward, and Mick “Woody” Woodmansey