The Pearl Theatre tackles Aaron Posner’s “sort-of” adaptation of Chekhov’s THE SEAGULL, STUPID FUCKING BIRD (photo by Russ Rowland)

The Pearl Theatre

555 West 42nd St. between Tenth & Eleventh Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through May 8, $60-$80

212-563-9261

www.pearltheatre.org

If the title of the current production at the Pearl didn’t already prepare you for something unusual at the theater that houses “New York’s only classical resident company,” then perhaps the flimsy wall of doors onstage painted with huge letters spelling out the name as well as a Warholesque-posterized photograph of Anton Chekhov would give you a hint. And if you’re still not sure, you’ll probably catch on once a young man comes out, looks at the audience, and says, “The play will begin when someone says: ‘Start the fucking play.’” As he’s hit with a barrage of shouts of “Start the fucking play” from a suddenly roused crowd, the play does indeed start. And the audience-actor barrages continue to fly for the next two hours, a raucous romp through the world created by Chekhov in his 1896 tragicomic favorite, The Seagull. Aaron Posner, a former actor and longtime Shakespeare director who has written reverent adaptations of Chaim Potok’s The Chosen and My Name Is Asher Lev and Ken Kesey’s Sometimes a Great Notion, is now in the midst of a quartet of irreverent Chekhov adaptations, or, as he warns, “sort of adapted.” Stupid Fucking Bird furiously breaks down the barriers between actor, character, and audience, between truth, reality, and fiction, as it investigates unrequited love, lust, and the value of art. Conrad Arkadina (Christopher Sears), known as Con, is putting on a show featuring his girlfriend, Nina (Marianna McClellan), in the lakefront backyard belonging to his mother, superstar actress Emma Arkadina (Bianca Amato). Emma is joined by her lover, famous writer Doyle Trigorin (Erik Lochtefeld), and her relatively plainspoken brother, Dr. Eugene Sorn (Dan Daily). Also on hand for the “site-specific performance event” are Con’s best friend, the well-meaning, very odd Dev (Joe Paulik), and the dark, brooding Mash (Joey Parsons). Dev loves Mash, Mash loves Con, Con loves Nina, his muse, but Nina is instantly attracted to Trigorin, setting in motion some fab relationship confrontations alternating between sad and pathetic and sexy and funny. The conceit is that not only is this a play-within-a-play, it’s a play-within-a-play by actors who understand that they are performing a play for an audience, as made clear when it all begins. “This is a play. There is simply more than one reality going on at a time,” Posner explains in a “Meta-Theatrics” stage note.

Nina (Marianna McClellan) stars in her boyfriend’s play-within-a-play in STUPID FUCKING BIRD (photo by Russ Rowland)

Con’s supposedly cutting-edge performance piece with Nina is a pretentious piece of claptrap, even if Emma never gives it a fair chance, and Stupid Fucking Bird has every possibility of being a piece of pretentious claptrap as well. But it skillfully avoids such a fate over and over again through its clever dialogue, superb acting, and fearless direction by Davis McCallum (The Whale, Water by the Spoonful), a Shakespeare veteran who has recently helmed such rediscovered old treasures as Fashions for Men and London Wall at the Mint. Sears (London Wall, Third) is an aggressive whirlwind as Con, overcome with an endless supply of energy and rage that he can’t rein in. Paulik (A Feminine Ending, P.S. Jones and the Frozen City) is a hoot as Dev, a simple, soft-spoken young man who tries to find the good in life even though he is poor and unloved. Pearl veteran Parsons (The Rivals, The Misanthrope) is wonderfully gloomy as the dour goth Mash, who dresses in black and occasionally breaks out her ukulele and sings a sad song (“Life is a muddle / Life is a chore / Life is a burden / Life is a bore”). Daily (The Dining Room, Sin: A Cardinal Deposed) is downright amiable as the friendly Sorn, a combination of Sorin and Dorn from Chekhov’s original, while Lochtefeld (Small Mouth Sounds, February House) and McClellan (#liberated, Cherry Smoke) make a fine pair of potential cheating lovers. And Amato (Arcadia, The Coast of Utopia) does a grand star turn as the self-obsessed diva determined to maintain her career success — and her sexuality.

The actors go in and out of character as they explore love and death, art and sex in irreverent Chekhov adaptation (photo by Russ Rowland)

Stupid Fucking Bird is very much about making connections, among the actors, the characters, and the audience; at several points, members of the audience are asked to participate, although at other times the questions posed apparently to them are actually rhetorical. The physical space is broken down too; the first act takes place in front of the wall of doors, a space recognized as the front of the stage, but the second and third acts are set in the kitchen of the lake house as actions occur somewhat more conventionally from a theatrical perspective, although you should still expect the unexpected, particularly when the actors venture into the audience. (The stage design is by Derek Dickinson.) You don’t have to know anything about The Seagull to thoroughly enjoy this passionate, free-wheeling marvel of a production, chock-full of self-referential commentary on itself and the theater in general, with tongue in cheek as well as sticking out at everyone and everything with humor, cynicism, and sarcasm while staying true to the spirit of Chekhov’s original. (Posner’s second Chekov “irreverent variation” is Life Sucks, or the Present Ridiculous, based on Uncle Vanya.) “Life is disappointing,” Mash sings early on. “You try you die so why begin / It’s all a game you’ll never win.” When life includes such deliriously chaotic yet controlled rave-ups like Stupid Fucking Bird, there’s nothing disappointing about it at all.

Akira Kurosawa’s thrilling police procedural, Stray Dog, is one of the all-time-great film noirs. When newbie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) gets his Colt lifted on a trolley, he fears he’ll be fired if he does not get it back. But as he searches for the weapon, he discovers that it is being used in a series of robberies and murders — for which he feels responsible. Teamed with seasoned veteran Sato (Takashi Shimura), Murakami risks his career — and his life — as he tries desperately to track down his gun before it is used again. Kurosawa makes audiences sweat, showing postwar Japan in the midst of a brutal heat wave, with Murakami, Sato, dancer Harumi Namiki (Keiko Awaji), and others constantly mopping their brows — the heat is so palpable, you can practically see it dripping off the screen. (You’ll find yourself feeling relieved when Sato hits a button on a desk fan, causing it to turn toward his face.) In his third of sixteen films made with Kurosawa, Mifune plays Murakami with a stalwart vulnerability, working beautifully with Shimura’s cool, calm cop who has seen it all and knows how to handle just about every situation. (Shimura was another Kurosawa favorite, appearing in twenty-one of his films.)

Akira Kurosawa’s thrilling police procedural, Stray Dog, is one of the all-time-great film noirs. When newbie detective Murakami (Toshirō Mifune) gets his Colt lifted on a trolley, he fears he’ll be fired if he does not get it back. But as he searches for the weapon, he discovers that it is being used in a series of robberies and murders — for which he feels responsible. Teamed with seasoned veteran Sato (Takashi Shimura), Murakami risks his career — and his life — as he tries desperately to track down his gun before it is used again. Kurosawa makes audiences sweat, showing postwar Japan in the midst of a brutal heat wave, with Murakami, Sato, dancer Harumi Namiki (Keiko Awaji), and others constantly mopping their brows — the heat is so palpable, you can practically see it dripping off the screen. (You’ll find yourself feeling relieved when Sato hits a button on a desk fan, causing it to turn toward his face.) In his third of sixteen films made with Kurosawa, Mifune plays Murakami with a stalwart vulnerability, working beautifully with Shimura’s cool, calm cop who has seen it all and knows how to handle just about every situation. (Shimura was another Kurosawa favorite, appearing in twenty-one of his films.)

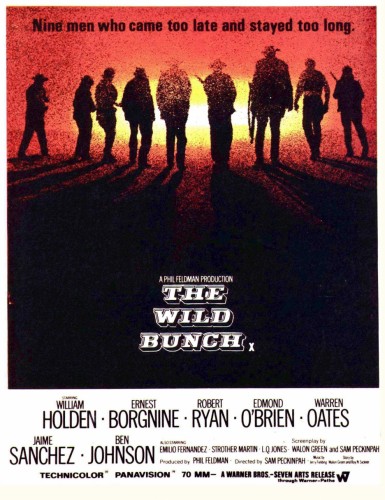

Sam Peckinpah cemented his reputation for graphic violence and eclectic storytelling with the genre-redefining 1969 Western The Wild Bunch. When a robbery goes seriously wrong, Pike Bishop (William Holden), Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine), Freddie Sykes (Edmond O’Brien), Angel (Jaime Sánchez), and brothers Lyle (Warren Oates) and Tector Gorth (Ben Johnson) set out to get even, planning an even bigger score by going after a U.S. Army weapons shipment on a railroad protected by detective Pat Harrigan (Albert Dekker) and his hired gun, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who is given nothing but “egg-suckin’, chicken-stealing gutter trash” to work with, including the hapless Coffer (Strother Martin) and T.C. (L. Q. Jones). The aging Pike, who sees this as his last score, is worried about being in cahoots with the unpredictable General Mapache (Emilio Fernández), a local warlord battling Pancho Villa’s freedom forces. But at the center of the film is the cat-and-mouse game between Pike and Thornton, the latter determined to capture his former partner, who left him to rot in jail years earlier. It all comes to a head in Agua Verde, which might translate to “Green Water” but will soon be bathed in red blood in one of the most violent shoot-outs ever depicted on celluloid.

Sam Peckinpah cemented his reputation for graphic violence and eclectic storytelling with the genre-redefining 1969 Western The Wild Bunch. When a robbery goes seriously wrong, Pike Bishop (William Holden), Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine), Freddie Sykes (Edmond O’Brien), Angel (Jaime Sánchez), and brothers Lyle (Warren Oates) and Tector Gorth (Ben Johnson) set out to get even, planning an even bigger score by going after a U.S. Army weapons shipment on a railroad protected by detective Pat Harrigan (Albert Dekker) and his hired gun, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), who is given nothing but “egg-suckin’, chicken-stealing gutter trash” to work with, including the hapless Coffer (Strother Martin) and T.C. (L. Q. Jones). The aging Pike, who sees this as his last score, is worried about being in cahoots with the unpredictable General Mapache (Emilio Fernández), a local warlord battling Pancho Villa’s freedom forces. But at the center of the film is the cat-and-mouse game between Pike and Thornton, the latter determined to capture his former partner, who left him to rot in jail years earlier. It all comes to a head in Agua Verde, which might translate to “Green Water” but will soon be bathed in red blood in one of the most violent shoot-outs ever depicted on celluloid.