Edvard Munch, “Self Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” oil on canvas, 1940–43 (© 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / photo © Munch Museum)

The Met Breuer

945 Madison Ave. at 75th St.

Tuesday – Sunday through February 4, suggested admission $12-$25

212-535-7710

www.metmuseum.org

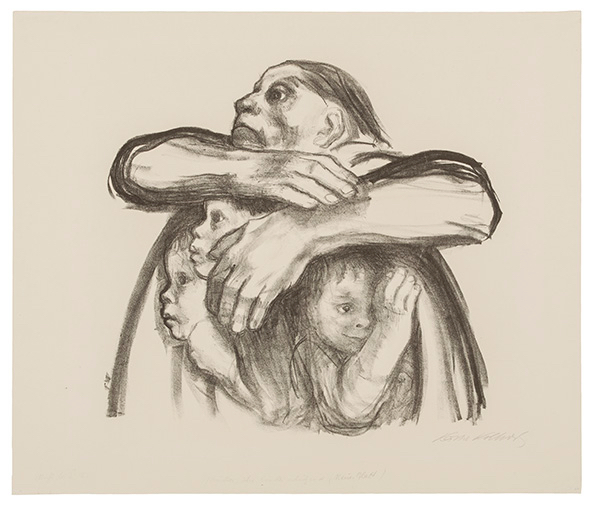

The Met Breur’s exemplary exhibition “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” is anchored by the Norwegian artist’s remarkable “Self-Portrait between the Clock and the Bed,” which Munch worked on from 1940 to 1943. When the painting was completed, Munch was eighty; he passed away the following year. His last major self-portrait, it’s an exquisite reckoning of a man’s life. Munch pictures himself standing straight, eyes slightly closed, his hands at his sides. To his right is a grandfather clock that is a virtual doppelgänger for the artist, the round face and three sections mimicking Munch’s head, upper body, and legs. He knows his time is running out, and in true Munch style, he is none too happy about it, though seemingly resigned to his fate. To his left are representations of some of his other paintings as well as a bed with black and red cross hatches, which may be where he goes to sleep for the last time and never wakes up. The wide range of colors counterbalance the somber mood; this might be a kind of farewell from Munch, but it could be anybody facing mortality. At the beginning of his catalog preface “On Edvard Munch,” novelist Karl Ove Knausgaard writes, “‘My art has been an act of confession.’ So said Edvard Munch at the end of his life. I believe that anyone who has seen Munch’s paintings will understand that remark. Not only because he painted so many self-portraits, or because so many of the stock scenes he returned to again and again have clearly autobiographical elements, but because it’s as if something is revealed in everything he painted, even the landscapes without people, a field covered in snow, a jetty by the shore, a pine forest in the gloam. This is the essence of Munch’s art. But also what we can say least about.” Museumgoers will understand that and more after seeing the fifty works on view at the Breuer through February 4, several of which have never been shown publicly before and were part of Munch’s personal collection. “In fact,” Knausgaard (Out of the World, Min Kamp) continues, “the question is rather whether it is possible to say anything about the essence of Munch’s paintings at all. The paintings are wordless, they are silent and unmoving. They are made up of colors and shapes and they touch us in a way that words never can, they reach places in us where words have no access.”

Edvard Munch, “The Dance of Life,” oil on canvas, 1925 (Munch Museum, Oslo / © 2017 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

The exhibition is divided into seven sections whose titles alone capture the essence of Munch’s oeuvre: “Self-Portraits,” “Nocturnes,” “Despair,” “Sickness and Death,” “Puberty and Passion,” “Attraction and Repulsion,” and “In the Studio.” In the 1906 “Self-Portrait with a Bottle of Wine,” Munch sits in the foreground, looking contemplative and forlorn, his hands clasped in his lap, the loose brushwork placing him in an undetermined reality; he would suffer a nervous breakdown two years later. In two renditions of “The Sick Child,” Munch revisits the death of his beloved sister Sophie, who died from tuberculosis in 1877 at the age of fifteen; in the 1896 painting, Sophie is accepting of her fate, offering solace to her distraught mother, while the brushwork in the 1906 version, in which Munch layered paint and then scraped away color, creates an angrier, more expressionistic scene. Munch, who never married, explores sexuality and romance in “Madonna” and “The Kiss”; the former turns Jesus’s mother into a passionate woman, while the latter melds the two lovers’ faces into one. A lithographic crayon version of Munch’s most famous image, “The Scream,” features the handprinted text “I felt a loud, unending scream piercing nature”; nearby is a photograph of the Ljaborveien road that was the setting for the iconic work. The 1925 oil painting “The Dance of Life” is a more experimental version of the 1899–1900 original, depicting the three stages of a woman’s life as she ages — youthful in white, seductive in red, mourning in black — but it is also more dour despite the light glistening over the ocean. Other extraordinary pieces include “Sick Mood at Sunset: Despair,” “Moonlight,” “Puberty,” “Weeping Nude,” two versions of “The Artist and His Model,” “Death in the Sick Room,” and “The Night Wanderer,” which reveals Munch hunched over, unable to sleep, restless and uneasy, not knowing what to do and where to go next. “Edvard Munch: Between the Clock and the Bed” is an intense, emotional, deeply psychological journey into the abyss as portrayed by a supremely talented and innovative artist overwhelmed by mental anguish. (In Midtown, coinciding with the Met Breuer show, Scandinavia House has just extended “The Experimental Self: Edvard Munch’s Photography,” consisting of photographs, film, and prints, through April 4.)

Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien’s first film in eight years is a visually sumptuous feast, perhaps the most beautifully poetic wuxia film ever made. Inspired by a chuanqi story by Pei Xing, The Assassin is set during the ninth-century Tang dynasty, on the brink of war between Weibo and the Royal Court. Exiled from her home since she was ten, Nie Yinniang (Hou muse Shu Qi) has returned thirteen years later, now an expert assassin, trained by the nun (Fang-Yi Sheu) who raised her to be a cold-blooded killer out for revenge. After being unable to execute a hit out of sympathy for her target’s child, Yinniang is ordered to kill Tian Ji’an (Chang Chen), her cousin and the man to whom she was betrothed as a young girl, as a lesson to teach her not to let personal passions rule her. But don’t worry about the plot, which is far from clear and at times impossible to follow. Instead, glory in Hou’s virtuosity as a filmmaker; he was named Best Director at Cannes for The Assassin, a meditative journey through a fantastical medieval world. Hou and cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing craft each frame like it’s a classical Chinese painting, a work of art unto itself. The camera moves slowly, if at all, as the story plays out in long shots, in both time and space, with very few close-ups and no quick cuts, even during the martial arts fights in which Yinniang displays her awesome skills. Hou often lingers on her face, which shows no outward emotion, although her soul is in turmoil. Hou evokes Andrei Tarkovsky, Akira Kurosawa, Ang Lee, and Zhang Yimou as he takes the viewer from spectacular mountains and river valleys to lush interiors (the stunning sets and gorgeous costumes, bathed in red, black, and gold, are by Hwarng Wern-ying), with silk curtains, bamboo and birch trees, columns, and other elements often in the foreground, along with mist, fog, and smoke, occasionally obscuring the proceedings, lending a surreal quality to Hou’s innate realism.

Taiwanese master Hou Hsiao-hsien’s first film in eight years is a visually sumptuous feast, perhaps the most beautifully poetic wuxia film ever made. Inspired by a chuanqi story by Pei Xing, The Assassin is set during the ninth-century Tang dynasty, on the brink of war between Weibo and the Royal Court. Exiled from her home since she was ten, Nie Yinniang (Hou muse Shu Qi) has returned thirteen years later, now an expert assassin, trained by the nun (Fang-Yi Sheu) who raised her to be a cold-blooded killer out for revenge. After being unable to execute a hit out of sympathy for her target’s child, Yinniang is ordered to kill Tian Ji’an (Chang Chen), her cousin and the man to whom she was betrothed as a young girl, as a lesson to teach her not to let personal passions rule her. But don’t worry about the plot, which is far from clear and at times impossible to follow. Instead, glory in Hou’s virtuosity as a filmmaker; he was named Best Director at Cannes for The Assassin, a meditative journey through a fantastical medieval world. Hou and cinematographer Mark Lee Ping-Bing craft each frame like it’s a classical Chinese painting, a work of art unto itself. The camera moves slowly, if at all, as the story plays out in long shots, in both time and space, with very few close-ups and no quick cuts, even during the martial arts fights in which Yinniang displays her awesome skills. Hou often lingers on her face, which shows no outward emotion, although her soul is in turmoil. Hou evokes Andrei Tarkovsky, Akira Kurosawa, Ang Lee, and Zhang Yimou as he takes the viewer from spectacular mountains and river valleys to lush interiors (the stunning sets and gorgeous costumes, bathed in red, black, and gold, are by Hwarng Wern-ying), with silk curtains, bamboo and birch trees, columns, and other elements often in the foreground, along with mist, fog, and smoke, occasionally obscuring the proceedings, lending a surreal quality to Hou’s innate realism.

During his sixteen-year career, Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke has made both narrative works (The World, Platform, Still Life) and documentaries (Useless, I Wish I Knew), with his fiction films containing elements of nonfiction and vice versa. Such is the case with his 2013 film, the powerful A Touch of Sin, which explores four based-on-fact outbreaks of shocking violence in four different regions of China. In Shanxi, outspoken miner Dahai (Jiang Wu) won’t stay quiet about the rampant corruption of the village elders. In Chongqing, married migrant worker and father Zhao San (Wang Baoqiang) obtains a handgun and is not afraid to use it. In Hubei, brothel receptionist Ziao Yu (Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime muse and wife) can no longer take the abuse and assumptions of the male clientele. And in Dongguan, young Xiao Hui (Luo Lanshan) tries to make a life for himself but is soon overwhelmed by his lack of success. Inspired by King Hu’s 1971 wuxia film A Touch of Zen, Jia also owes a debt to Max Ophüls’s 1950 bittersweet romance La Ronde, in which a character from one segment continues into the next, linking the stories. In A Touch of Sin, there is also a character connection in each successive tale, though not as overt, as Jia makes a wry, understated comment on the changing ways that people connect in modern society. In depicting these four acts of violence, Jia also exposes the widening economic gap between the rich and the poor and the social injustice that is prevalent all over contemporary China — as well as the rest of the world — leading to dissatisfied individuals fighting for their dignity in extreme ways. A gripping, frightening film that earned Jia the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes, A Touch of Zen is screening January 30 and 31 in the Metrograph series “Martial/Art,” which continues through February 10 with such other high-end martial-arts fare as Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Zhang Yimou’s Hero, and, appropriately enough, King Hu’s A Touch of Zen.

During his sixteen-year career, Sixth Generation Chinese filmmaker Jia Zhangke has made both narrative works (The World, Platform, Still Life) and documentaries (Useless, I Wish I Knew), with his fiction films containing elements of nonfiction and vice versa. Such is the case with his 2013 film, the powerful A Touch of Sin, which explores four based-on-fact outbreaks of shocking violence in four different regions of China. In Shanxi, outspoken miner Dahai (Jiang Wu) won’t stay quiet about the rampant corruption of the village elders. In Chongqing, married migrant worker and father Zhao San (Wang Baoqiang) obtains a handgun and is not afraid to use it. In Hubei, brothel receptionist Ziao Yu (Zhao Tao, Jia’s longtime muse and wife) can no longer take the abuse and assumptions of the male clientele. And in Dongguan, young Xiao Hui (Luo Lanshan) tries to make a life for himself but is soon overwhelmed by his lack of success. Inspired by King Hu’s 1971 wuxia film A Touch of Zen, Jia also owes a debt to Max Ophüls’s 1950 bittersweet romance La Ronde, in which a character from one segment continues into the next, linking the stories. In A Touch of Sin, there is also a character connection in each successive tale, though not as overt, as Jia makes a wry, understated comment on the changing ways that people connect in modern society. In depicting these four acts of violence, Jia also exposes the widening economic gap between the rich and the poor and the social injustice that is prevalent all over contemporary China — as well as the rest of the world — leading to dissatisfied individuals fighting for their dignity in extreme ways. A gripping, frightening film that earned Jia the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes, A Touch of Zen is screening January 30 and 31 in the Metrograph series “Martial/Art,” which continues through February 10 with such other high-end martial-arts fare as Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Zhang Yimou’s Hero, and, appropriately enough, King Hu’s A Touch of Zen.