Godzilla emerges from the ocean after nuclear testing in classic monster movie

GHOSTS AND MONSTERS: POSTWAR JAPANESE HORROR

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Pl. & St. Felix St.

October 26 – November 1

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

Wanna see something really scary? Then head over to BAMcinématek to see any one of the nine fright flicks comprising “Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror,” running October 26 to November 1. No one makes scary movies like the Japanese do, and the 1950s and 1960s were a particular fertile time in the aftermath of WWII and the fear of global nuclear war. BAM is showing a great mix of films as Halloween approaches, with fantasy and sci-fi, blood and gore, monsters and aliens, and psychological mayhem. You can’t go wrong with any of them; below is only some of the awesomeness. (Also on the schedule are Ishirô Honda’s Mothra, Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Pitfall, and Kaneto Shindô’s Onibaba.)

Ishirō Honda has a smoke with his atomic-gas-breathing monster on the set of Godzilla

GODZILLA (Ishirō Honda, 1954)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

Friday, October 26, 2:00, 4:30, 7:00

www.bam.org

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On October 26, BAMcinématek is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of “Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror.” The film was inspired by Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a real incident involving the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a tuna-fishing boat that got hit by radioactive fallout in January 1954 from a U.S. test of a dry-fuel thermonuclear device in the Pacific Ocean. Writer-director Ishirō Honda and cowriter Takeo Murata expanded on Shigeru Kayama’s story, focusing on a giant dinosaur under the sea who comes back to life after H-bomb testing by the U.S. Standing 165 feet tall and able to breathe atomic gas, Godzilla — known as Gojira in Japanese, a combination of gorira, the Japanese word for gorilla, and kujira, which means whale — wreaks havoc on Japanese towns as he makes his way toward Tokyo. While the military and the government want to destroy the creature — who is played by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka in a monster suit, tramping over miniature houses, streets, cars, trains, and buildings using the suitmation technique (both men also make cameos outside the costume) — Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study Godzilla to find out how the radiation only makes it stronger instead of destroying it. (Throughout, Godzilla is referred to as “it” and not “he,” perhaps because the creature is in part a representation of America and what it wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) “Godzilla was baptized in the fire of the H-bomb and survived. What could kill it now?” Dr. Yamane asks. Meanwhile, one of Dr. Yamane’s assistants, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), is working on a secret oxygen destroyer that he will show only to his fiancée, Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), who is having trouble telling Dr. Serizawa that she is actually in love with salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada). “Godzilla’s no different from the H-bomb still hanging over Japan’s head,” Ogata tells Dr. Yamane, who is none too pleased with his take on the situation. Through it all, the media risks everything to get the story.

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On October 26, BAMcinématek is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of “Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror.” The film was inspired by Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a real incident involving the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a tuna-fishing boat that got hit by radioactive fallout in January 1954 from a U.S. test of a dry-fuel thermonuclear device in the Pacific Ocean. Writer-director Ishirō Honda and cowriter Takeo Murata expanded on Shigeru Kayama’s story, focusing on a giant dinosaur under the sea who comes back to life after H-bomb testing by the U.S. Standing 165 feet tall and able to breathe atomic gas, Godzilla — known as Gojira in Japanese, a combination of gorira, the Japanese word for gorilla, and kujira, which means whale — wreaks havoc on Japanese towns as he makes his way toward Tokyo. While the military and the government want to destroy the creature — who is played by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka in a monster suit, tramping over miniature houses, streets, cars, trains, and buildings using the suitmation technique (both men also make cameos outside the costume) — Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study Godzilla to find out how the radiation only makes it stronger instead of destroying it. (Throughout, Godzilla is referred to as “it” and not “he,” perhaps because the creature is in part a representation of America and what it wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) “Godzilla was baptized in the fire of the H-bomb and survived. What could kill it now?” Dr. Yamane asks. Meanwhile, one of Dr. Yamane’s assistants, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), is working on a secret oxygen destroyer that he will show only to his fiancée, Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), who is having trouble telling Dr. Serizawa that she is actually in love with salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada). “Godzilla’s no different from the H-bomb still hanging over Japan’s head,” Ogata tells Dr. Yamane, who is none too pleased with his take on the situation. Through it all, the media risks everything to get the story.

Even for 1954, many of the special effects, photographed by Masao Tamai, are cheesy but fun, and composer Akira Ifukube’s fiercely dramatic score goes toe-to-toe with the monster. The Toho film is no mere monster movie but instead is filled with metaphors and references about WWII and the use of atomic bombs, examining it from political and socioeconomic vantage points while questioning the future of technological advances. “But what if your discovery is used for some horrible purpose?” Emiko asks Dr. Serizawa, who wears an eye patch, as if he can only see part of things. Godzilla could only have come from Japan, much like King Kong was purely an American creation produced by Hollywood; in fact, the two went at it in Honda’s 1962 film, King Kong vs. Godzilla. The next year, Akira Kurosawa would make I Live in Fear (Ikimono no kiroku), an intense psychological drama about the nuclear holocaust’s effects on one man, a factory owner played by Toshirô Mifune — who meets with a dentist portrayed by Kurosawa regular Shimura — a kind of companion piece to Godzilla. Honda, who served as an assistant director to Kurosawa on many films before making his own pictures, would go on to make such other sci-fi flicks as Rodan, The H-Man, Mothra, and Destroy All Monsters, but it was on Godzilla that he got everything right, capturing the fate of a nation in the aftermath of nuclear devastation while still managing to gain sympathy for the monster. It is also difficult to watch the film in 2018 without thinking of America’s current debate over illegal immigration and fear of the other, particularly when Godzilla approaches an electrified fence meant to keep him out, as well as the threat of nuclear war.

Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell is part of BAMcinématek tribute to Japanese horror films

GOKE, BODY SNATCHER FROM HELL (Hajime Satô, 1968)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Pl. & St. Felix St.

Saturday, October 27, 9:30

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

Birds start slamming into the windows of an airplane. The sky has turned a deep red. “It’s just like flying through a sea of blood,” first officer Ei Sugisaka (Teruo Yoshida) says. It’s reported that a bomb might be on board the aircraft. A suitcase with a rifle is discovered. A spectacular yellow UFO buzzes over the plane, which catches fire and crashes in a vast postapocalyptic wasteland in the middle of nowhere, as if on a deserted planet. And then the real trouble begins in Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell, a color-saturated nightmare released by Shochiko in 1968. The survivors include the stalwart and dedicated Captain Sugisaka; sweet and innocent flight attendant Kazumi Asakura (Tomomi Saito); corrupt politician Gôzô Mano (Eizo Kitamura); weapons dealer Tokuyasu (Nobu Kaneko), who is so desperate to make a sale that he offers his wife, Noriko Tokuyasu (Yûko Kusunoki), to Mano; a blonde American, Mrs. Neal (Kathy Horan), who is picking up the body of her dead husband, who was killed in the Vietnam War; Momotake (Kazuo Kato), a psychiatrist who sees this as a great opportunity to study human nature in a time of severe crisis; Professor Sagai (Hideo Masaya Takahashi), a space biologist with some wacky theories; Hirofumi Teraoka (Hideo Ko), a suspicious passenger in a white suit and sunglasses; and Matsumiya (Norihiko Yamamoto), the young bomber.

Birds start slamming into the windows of an airplane. The sky has turned a deep red. “It’s just like flying through a sea of blood,” first officer Ei Sugisaka (Teruo Yoshida) says. It’s reported that a bomb might be on board the aircraft. A suitcase with a rifle is discovered. A spectacular yellow UFO buzzes over the plane, which catches fire and crashes in a vast postapocalyptic wasteland in the middle of nowhere, as if on a deserted planet. And then the real trouble begins in Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell, a color-saturated nightmare released by Shochiko in 1968. The survivors include the stalwart and dedicated Captain Sugisaka; sweet and innocent flight attendant Kazumi Asakura (Tomomi Saito); corrupt politician Gôzô Mano (Eizo Kitamura); weapons dealer Tokuyasu (Nobu Kaneko), who is so desperate to make a sale that he offers his wife, Noriko Tokuyasu (Yûko Kusunoki), to Mano; a blonde American, Mrs. Neal (Kathy Horan), who is picking up the body of her dead husband, who was killed in the Vietnam War; Momotake (Kazuo Kato), a psychiatrist who sees this as a great opportunity to study human nature in a time of severe crisis; Professor Sagai (Hideo Masaya Takahashi), a space biologist with some wacky theories; Hirofumi Teraoka (Hideo Ko), a suspicious passenger in a white suit and sunglasses; and Matsumiya (Norihiko Yamamoto), the young bomber.

Nearby, the Gokemidoro ship glows like it’s an acid trip, but anyone who gets too close is invaded by the species, with extraterrestrial goop entering through a newly created vaginal slit in the human’s head. Tempers flare, flirtations rise up, and the Earth is in danger in this certifiably crazy-ass film, in which Invasion of the Body Snatchers meets The Blob by way of Forbidden Planet, Dracula, and The Day the Earth Stood Still. The film, a favorite of Quentin Tarantino’s, was written by Susumi Takahasi and Kyuzo Kobayashi and photographed by Shizuo Hirase, with awesome art direction by Masataka Kayano and a Theramin-heavy score by Toshiwa Kikuchi. So what’s it all really about? There’s a thick antiwar sentiment — television and superhero veteran Satô (Captain Ultra, The Terror Beneath the Sea) occasionally cuts to images from Vietnam, bathed in red — and a general lack of humanity pervades. “The end has come and mankind is on the verge of destruction,” the Gokemidoro declare. No kidding.

Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) makes his pottery as son Genichi (Ikio Sawamura) and wife Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka) look on in UGETSU

UGETSU (UGETSU MONOGATARI) (Kenji Mizoguchi, 1953)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

Saturday, October 27, 7:00

www.bam.org

BAMcinématek is presenting a 4K restoration of one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film, Ugetsu, is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool. “I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.

BAMcinématek is presenting a 4K restoration of one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film, Ugetsu, is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool. “I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.

Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō) admires Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) in Kenji Mizoguchi postwar masterpiece

Written by longtime Mizoguchi collaborator Yoshitaka Yoda and Matsutaro Kawaguchi, Ugetsu might be set in the sixteenth century, but it is also very much about the aftereffects of World War II. “The war drove us mad with ambition,” Tōbei says at one point. Photographed in lush, shadowy black-and-white by Kazuo Miyagawa (Rashomon, Floating Weeds, Yojimbo), the film features several gorgeous set pieces, including one that takes place on a foggy lake and another in a hot spring, heightening the ominous atmosphere that pervades throughout. Ugetsu ends much like it began, emphasizing that it is but one postwar allegory among many. Kyō (Gate of Hell, The Face of Another) is magical as the temptress Lady Wakasa, while Mori (The Bad Sleep Well, When a Woman Ascends the Stairs) excels as the everyman who follows his dreams no matter the cost; the two previously played husband and wife in Rashomon Mizoguchi, who made such other unforgettable classics as The 47 Ronin, The Life of Oharu, Sansho the Bailiff, and Street of Shame, passed away in 1956 at the age of fifty-eight, having left behind a stunning legacy, of which Ugetsu might be the best, and now looking better than ever.

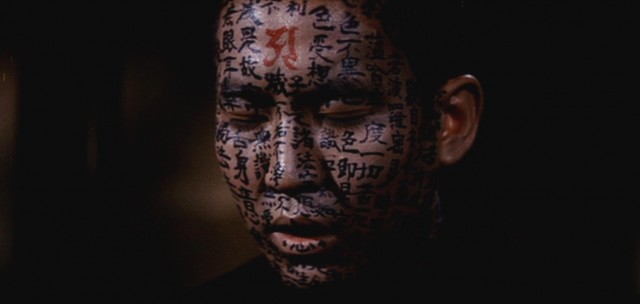

Masaki Kobayashi paints four chilling, ghostly portraits in KWAIDAN, including “Hoichi, the Earless”

KWAIDAN (Masaki Kobayashi, 1964)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

Sunday, October 28, 2:00

www.bam.org

In the mesmerizing Kwaidan, based on folkloric tales by Lafcadio Hearn, aka Koizumi Yakumo, Masaki Kobayashi (The Human Condition, Samurai Rebellion) paints four marvelous ghost stories, each one with a unique look and feel. In “The Black Hair,” a samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) regrets his choice of leaving his true love for societal advancement. Yuki (Keiko Kishi) is a harbinger of doom for a woodcutter (Nakadai) in “The Woman of the Snow.” Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) must have his entire body covered in prayer in “Hoichi, the Earless.” And Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura) finds a creepy face staring back at him in “In a Cup of Tea.” The four films subtly, and not so subtly, explore such concepts as greed and envy, love and loss, and the art of storytelling itself. Winner of the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, Kwaidan is one of the greatest ghost story films ever made, a quartet of chilling existential tales that will get under your skin and into your brain. The score was composed by Tōru Takemitsu, who said of the film, “I wanted to create an atmosphere of terror.” He succeeded.

In the mesmerizing Kwaidan, based on folkloric tales by Lafcadio Hearn, aka Koizumi Yakumo, Masaki Kobayashi (The Human Condition, Samurai Rebellion) paints four marvelous ghost stories, each one with a unique look and feel. In “The Black Hair,” a samurai (Rentaro Mikuni) regrets his choice of leaving his true love for societal advancement. Yuki (Keiko Kishi) is a harbinger of doom for a woodcutter (Nakadai) in “The Woman of the Snow.” Hoichi (Katsuo Nakamura) must have his entire body covered in prayer in “Hoichi, the Earless.” And Kannai (Kanemon Nakamura) finds a creepy face staring back at him in “In a Cup of Tea.” The four films subtly, and not so subtly, explore such concepts as greed and envy, love and loss, and the art of storytelling itself. Winner of the Special Jury Prize at Cannes, Kwaidan is one of the greatest ghost story films ever made, a quartet of chilling existential tales that will get under your skin and into your brain. The score was composed by Tōru Takemitsu, who said of the film, “I wanted to create an atmosphere of terror.” He succeeded.

Shirō Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi) is trapped in the realms of hell in Nobuo Nakagawa’s awesome Jigoku

JIGOKU (THE SINNERS OF HELL) (Nobuo Nakagawa, 1960)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

30 Lafayette Ave. between Ashland Pl. & St. Felix St.

Sunday, October 28, 5:30

718-636-4100

www.bam.org

Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku is a dark, demonic masterpiece, a descent into the deepest circles of hell, where sinners face the swirling vortex of torment and rivers of pus and blood. Jigoku goes places that would make even Dante and Hieronymus Bosch turn away in fear while Roger Corman and Mario Bava rejoice. In the film, seemingly everyone theology student Shirō Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi) comes into contact with dies a tragic death. He and Yukiko Yajima (Utako Mitsuya) become engaged, but their lives change forever when Shirō and his friend Tamura (Yōichi Numata), a sociopath of pure evil, go for a ride and Tamura, behind the wheel, runs over gangster Kyōichi “Tiger” Shiga (Hiroshi Izumida) and drives away, showing no remorse whatsoever, reminiscent of Artie Strauss (Bradford Dillman) and Judd Steiner (Dean Stockwell) in Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion. However, Kyōichi’s mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) witnessed the hit-and-run and is determined to exact revenge, joined by Yoko (Akiko Ono), Kyōichi’s girlfriend.

Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku is a dark, demonic masterpiece, a descent into the deepest circles of hell, where sinners face the swirling vortex of torment and rivers of pus and blood. Jigoku goes places that would make even Dante and Hieronymus Bosch turn away in fear while Roger Corman and Mario Bava rejoice. In the film, seemingly everyone theology student Shirō Shimizu (Shigeru Amachi) comes into contact with dies a tragic death. He and Yukiko Yajima (Utako Mitsuya) become engaged, but their lives change forever when Shirō and his friend Tamura (Yōichi Numata), a sociopath of pure evil, go for a ride and Tamura, behind the wheel, runs over gangster Kyōichi “Tiger” Shiga (Hiroshi Izumida) and drives away, showing no remorse whatsoever, reminiscent of Artie Strauss (Bradford Dillman) and Judd Steiner (Dean Stockwell) in Richard Fleischer’s Compulsion. However, Kyōichi’s mother (Kiyoko Tsuji) witnessed the hit-and-run and is determined to exact revenge, joined by Yoko (Akiko Ono), Kyōichi’s girlfriend.

Nobuo Nakagawa’s Jigoku takes viewers on a dark journey through hell

Shirō is called home to visit his ill mother, Ito (Kimie Tokudaij), while his corrupt father, shady businessman Gōzō (Hiroshi Hayashi), shamelessly has an open affair with Kinuko (Akiko Yamashita). Shirō takes an instant liking to his mother’s nurse, Sachiko Taniguchi (Mitsuya), who looks almost exactly like Yukiko, but her father, painter Ensai Taniguchi (Jun Ōtomo), is being threatened by dirty Det. Hariya (Hiroshi Shingûji), who wants Sachiko for himself or else he will arrest Ensai for a long-ago crime. Sachiko’s appearance frightens Yukiko’s parents, Professor Yajima (Torahiko Nakamura), who is Shirō’s teacher, and his wife (Fumiko Miyata), who are shocked by the doppelgänger. Also hanging around are Dr. Kusama (Tomohiko Ōtani) and journalist Akagawa (Kôichi Miya), who have secrets of their own. As people start dropping like brutally swatted and electrocuted flies, Shirō takes all of the blame even though he does not cause any of the deaths directly. (Even the production studio, Shintoho, didn’t survive, declaring bankruptcy after releasing the film.)

But none of that matters once everyone is in hell, facing a series of horrific tortures that are spectacularly photographed by Mamoru Morita, who enjoys keeping the color red at or near the center of most images, along with occasional touches of blue and green. Inspired by the Ōjōyōshū, the tenth-century Buddhist text about birth, rebirth, and the realms of hell, Nakagawa cowrote the screenplay with Ichirō Miyagawa; Nakagawa made nearly one hundred films in just about every genre before he died in 1984 at the age of seventy-nine, but Jigoku is his crowning achievement. It’s horror of the highest order, immersed in a jaw-dropping madness. It’s also a warning, since everyone is a sinner in one way or another, and retribution awaits us all.

A black cat is not happy with the turn of events in Kaneto Shindô’s Kuroneko

KURONEKO (藪の中の黒猫) (Kaneto Shindô, 1968)

BAMcinématek, BAM Rose Cinemas

Wednesday, October 31, 7:00

www.bam.org

“A cat’s nothing to be afraid of,” a samurai (Rokkô Toura) says in Kaneto Shindô’s 1968 Japanese horror-revenge classic, Kuroneko. Oh, that poor, misguided warrior. He has much to learn about the feline species but not enough time to do it before he suffers a horrible death. In Sengoku-era Japan, a large group of hungry, bedraggled samurai come upon a house at the edge of a bamboo forest. Inside they find Yone (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law, Shige (Kiwao Taichi), whose husband, Hachi (Kichiemon Nakamura), is off fighting the war. The men viciously rob, rape, and murder the women, but they leave behind a mewing black cat (“kuroneko”) that is not exactly happy with what just happened. Three years later, the aforementioned samurai is riding his horse on a dark night when he encounters, by the Rajōmon Gate, a young woman positively glowing in the darkness. She says she is frightened and asks if he can accompany her home; he claims he has met her before but can’t quite place her. He agrees to help her, and when they reach her abode he is treated to some tea served by an older woman and some fooling around with the younger one — until the latter creeps on top of him and turns into a menacing animal, biting into his throat and drinking his blood. One by one, the samurai are lured into this trap, until a surprise warrior arrives.

“A cat’s nothing to be afraid of,” a samurai (Rokkô Toura) says in Kaneto Shindô’s 1968 Japanese horror-revenge classic, Kuroneko. Oh, that poor, misguided warrior. He has much to learn about the feline species but not enough time to do it before he suffers a horrible death. In Sengoku-era Japan, a large group of hungry, bedraggled samurai come upon a house at the edge of a bamboo forest. Inside they find Yone (Nobuko Otowa) and her daughter-in-law, Shige (Kiwao Taichi), whose husband, Hachi (Kichiemon Nakamura), is off fighting the war. The men viciously rob, rape, and murder the women, but they leave behind a mewing black cat (“kuroneko”) that is not exactly happy with what just happened. Three years later, the aforementioned samurai is riding his horse on a dark night when he encounters, by the Rajōmon Gate, a young woman positively glowing in the darkness. She says she is frightened and asks if he can accompany her home; he claims he has met her before but can’t quite place her. He agrees to help her, and when they reach her abode he is treated to some tea served by an older woman and some fooling around with the younger one — until the latter creeps on top of him and turns into a menacing animal, biting into his throat and drinking his blood. One by one, the samurai are lured into this trap, until a surprise warrior arrives.

A bamboo forest leads to a kind of hell for samurai in Kuroneko

Written and directed by Shindô and based on an old folktale, Kuroneko is a tense, spooky film, with a foreboding score by Hikaru Hayashi (Shindô’s The Naked Island and Onibaba) and shot in eerie black-and-white by Kiyomi Kuroda (Shindô’s Mother, Human, and Onibaba). One of the great feminist ghost stories, it’s like the missing sequel to Masaki Kobayashi’s Kwaidan, with elements of Akira Kurosawa’s Hidden Fortress and Rashomon thrown in, along with echoes of flying ninja movies. Memorable images abound: The two women, in ghostly white, float in the air; the camera weaves through the bamboo forest; a gruesome killer is beheaded. The film also features Kei Satō as Raiko, Hideo Kanze as Mikado, and Taiji Tonoyama as a farmer, but Kuroneko belongs to Shindô regular — and his lover and, later, his wife — Otowa, who appeared in nearly two dozen of his films, and Taichi, who also worked with such other directors as Keisuke Kinoshita, Mitsuo Yanagimachi, Yôji Yamada, and Shintarô Katsu before dying in a car accident in 1992 at the age of forty-eight. The two women go about their business with a calm and somewhat placid demeanor until they pounce, like cats luring mice to certain doom.

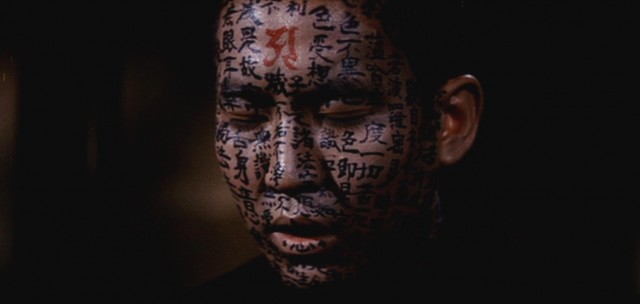

Antonio Méndez Esparza’s follow-up to his debut, Aquí y Allá, is a sensitive, beautifully paced film that lives up to its title: Life and Nothing More. Inspired by Italian neorealism, Esparza employs a cinema vérité style to tell the story of Regina (Regina Williams), an African American single mother struggling to get by in Florida. Regina has a delightful three-year-old daughter (Ry’Nesia Chambers) and a quiet, distant fourteen-year-old son, Andrew (Andrew Bleechington), who is starting to get in trouble with the law, hanging around with bad kids and carrying around a knife. Regina works menial minimum-wage jobs to try to keep the family afloat while the father of her children is in prison. Robert (Robert Williams), a newcomer to the town, starts trying to charm her, wanting to take her out, but Regina is suspicious of his intentions, as is Andrew. But when Robert shows the least bit of threatening anger as he and Andrew clash, Regina has some difficult decisions to make, which grow more complicated when other facts come to light.

Antonio Méndez Esparza’s follow-up to his debut, Aquí y Allá, is a sensitive, beautifully paced film that lives up to its title: Life and Nothing More. Inspired by Italian neorealism, Esparza employs a cinema vérité style to tell the story of Regina (Regina Williams), an African American single mother struggling to get by in Florida. Regina has a delightful three-year-old daughter (Ry’Nesia Chambers) and a quiet, distant fourteen-year-old son, Andrew (Andrew Bleechington), who is starting to get in trouble with the law, hanging around with bad kids and carrying around a knife. Regina works menial minimum-wage jobs to try to keep the family afloat while the father of her children is in prison. Robert (Robert Williams), a newcomer to the town, starts trying to charm her, wanting to take her out, but Regina is suspicious of his intentions, as is Andrew. But when Robert shows the least bit of threatening anger as he and Andrew clash, Regina has some difficult decisions to make, which grow more complicated when other facts come to light.

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On October 26, BAMcinématek is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of “Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror.” The film was inspired by Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a real incident involving the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a tuna-fishing boat that got hit by radioactive fallout in January 1954 from a U.S. test of a dry-fuel thermonuclear device in the Pacific Ocean. Writer-director Ishirō Honda and cowriter Takeo Murata expanded on Shigeru Kayama’s story, focusing on a giant dinosaur under the sea who comes back to life after H-bomb testing by the U.S. Standing 165 feet tall and able to breathe atomic gas, Godzilla — known as Gojira in Japanese, a combination of gorira, the Japanese word for gorilla, and kujira, which means whale — wreaks havoc on Japanese towns as he makes his way toward Tokyo. While the military and the government want to destroy the creature — who is played by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka in a monster suit, tramping over miniature houses, streets, cars, trains, and buildings using the suitmation technique (both men also make cameos outside the costume) — Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study Godzilla to find out how the radiation only makes it stronger instead of destroying it. (Throughout, Godzilla is referred to as “it” and not “he,” perhaps because the creature is in part a representation of America and what it wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) “Godzilla was baptized in the fire of the H-bomb and survived. What could kill it now?” Dr. Yamane asks. Meanwhile, one of Dr. Yamane’s assistants, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), is working on a secret oxygen destroyer that he will show only to his fiancée, Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), who is having trouble telling Dr. Serizawa that she is actually in love with salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada). “Godzilla’s no different from the H-bomb still hanging over Japan’s head,” Ogata tells Dr. Yamane, who is none too pleased with his take on the situation. Through it all, the media risks everything to get the story.

More than two dozen sequels, prequels, remakes, and reboots have not diluted in the slightest the grandeur of the original 1954 version of Godzilla, one of the greatest monster movies ever made. If you’ve only seen the feeble, reedited, Americanized Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, made two years later with Canadian-born actor Raymond Burr inserted as an American reporter, well, wipe that out of your head. On October 26, BAMcinématek is screening the real thing, the restored treasure as part of “Ghosts and Monsters: Postwar Japanese Horror.” The film was inspired by Eugène Lourié’s The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms and a real incident involving the Daigo Fukuryū Maru, a tuna-fishing boat that got hit by radioactive fallout in January 1954 from a U.S. test of a dry-fuel thermonuclear device in the Pacific Ocean. Writer-director Ishirō Honda and cowriter Takeo Murata expanded on Shigeru Kayama’s story, focusing on a giant dinosaur under the sea who comes back to life after H-bomb testing by the U.S. Standing 165 feet tall and able to breathe atomic gas, Godzilla — known as Gojira in Japanese, a combination of gorira, the Japanese word for gorilla, and kujira, which means whale — wreaks havoc on Japanese towns as he makes his way toward Tokyo. While the military and the government want to destroy the creature — who is played by Haruo Nakajima and Katsumi Tezuka in a monster suit, tramping over miniature houses, streets, cars, trains, and buildings using the suitmation technique (both men also make cameos outside the costume) — Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura) wants to study Godzilla to find out how the radiation only makes it stronger instead of destroying it. (Throughout, Godzilla is referred to as “it” and not “he,” perhaps because the creature is in part a representation of America and what it wrought in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.) “Godzilla was baptized in the fire of the H-bomb and survived. What could kill it now?” Dr. Yamane asks. Meanwhile, one of Dr. Yamane’s assistants, Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), is working on a secret oxygen destroyer that he will show only to his fiancée, Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kōchi), who is having trouble telling Dr. Serizawa that she is actually in love with salvage ship captain Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada). “Godzilla’s no different from the H-bomb still hanging over Japan’s head,” Ogata tells Dr. Yamane, who is none too pleased with his take on the situation. Through it all, the media risks everything to get the story.

Birds start slamming into the windows of an airplane. The sky has turned a deep red. “It’s just like flying through a sea of blood,” first officer Ei Sugisaka (Teruo Yoshida) says. It’s reported that a bomb might be on board the aircraft. A suitcase with a rifle is discovered. A spectacular yellow UFO buzzes over the plane, which catches fire and crashes in a vast postapocalyptic wasteland in the middle of nowhere, as if on a deserted planet. And then the real trouble begins in Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell, a color-saturated nightmare released by Shochiko in 1968. The survivors include the stalwart and dedicated Captain Sugisaka; sweet and innocent flight attendant Kazumi Asakura (Tomomi Saito); corrupt politician Gôzô Mano (Eizo Kitamura); weapons dealer Tokuyasu (Nobu Kaneko), who is so desperate to make a sale that he offers his wife, Noriko Tokuyasu (Yûko Kusunoki), to Mano; a blonde American, Mrs. Neal (Kathy Horan), who is picking up the body of her dead husband, who was killed in the Vietnam War; Momotake (Kazuo Kato), a psychiatrist who sees this as a great opportunity to study human nature in a time of severe crisis; Professor Sagai (Hideo Masaya Takahashi), a space biologist with some wacky theories; Hirofumi Teraoka (Hideo Ko), a suspicious passenger in a white suit and sunglasses; and Matsumiya (Norihiko Yamamoto), the young bomber.

Birds start slamming into the windows of an airplane. The sky has turned a deep red. “It’s just like flying through a sea of blood,” first officer Ei Sugisaka (Teruo Yoshida) says. It’s reported that a bomb might be on board the aircraft. A suitcase with a rifle is discovered. A spectacular yellow UFO buzzes over the plane, which catches fire and crashes in a vast postapocalyptic wasteland in the middle of nowhere, as if on a deserted planet. And then the real trouble begins in Hajime Satô’s Goke, Body Snatcher from Hell, a color-saturated nightmare released by Shochiko in 1968. The survivors include the stalwart and dedicated Captain Sugisaka; sweet and innocent flight attendant Kazumi Asakura (Tomomi Saito); corrupt politician Gôzô Mano (Eizo Kitamura); weapons dealer Tokuyasu (Nobu Kaneko), who is so desperate to make a sale that he offers his wife, Noriko Tokuyasu (Yûko Kusunoki), to Mano; a blonde American, Mrs. Neal (Kathy Horan), who is picking up the body of her dead husband, who was killed in the Vietnam War; Momotake (Kazuo Kato), a psychiatrist who sees this as a great opportunity to study human nature in a time of severe crisis; Professor Sagai (Hideo Masaya Takahashi), a space biologist with some wacky theories; Hirofumi Teraoka (Hideo Ko), a suspicious passenger in a white suit and sunglasses; and Matsumiya (Norihiko Yamamoto), the young bomber.

BAMcinématek is presenting a 4K restoration of one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film, Ugetsu, is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool. “I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.

BAMcinématek is presenting a 4K restoration of one of the most important and influential — and greatest — works to ever come from Japan. Winner of the Silver Lion for Best Director at the 1953 Venice Film Festival, Kenji Mizoguchi’s seventy-eighth film, Ugetsu, is a dazzling masterpiece steeped in Japanese storytelling tradition, especially ghost lore. Based on two tales by Ueda Akinari and Guy de Maupassant’s “How He Got the Legion of Honor,” Ugetsu unfolds like a scroll painting beginning with the credits, which run over artworks of nature scenes while Fumio Hayasaka’s urgent score starts setting the mood, and continues into the first three shots, pans of the vast countryside leading to Genjurō (Masayuki Mori) loading his cart to sell his pottery in nearby Nagahama, helped by his wife, Miyagi (Kinuyo Tanaka), clutching their small child, Genichi (Ikio Sawamura). Miyagi’s assistant, Tōbei (Sakae Ozawa), insists on coming along, despite the protestations of his nagging wife, Ohama (Mitsuko Mito), as he is determined to become a samurai even though he is more of a hapless fool. “I need to sell all this before the fighting starts,” Genjurō tells Miyagi, referring to a civil war that is making its way through the land. Tōbei adds, “I swear by the god of war: I’m tired of being poor.” After unexpected success with his wares, Genjurō furiously makes more pottery to sell at another market even as the soldiers are approaching and the rest of the villagers run for their lives. At the second market, an elegant woman, Lady Wakasa (Machiko Kyō), and her nurse, Ukon (Kikue Mōri), ask him to bring a large amount of his merchandise to their mansion. Once he gets there, Lady Wakasa seduces him, and soon Genjurō, Miyagi, Genichi, Tōbei, and Ohama are facing very different fates.