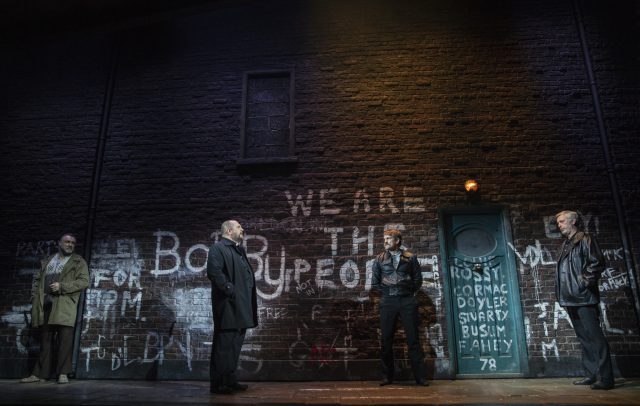

David Mandelbaum is Gogo and Eli Rosen is Didi in New Yiddish Rep production of Waiting for Godot (photo by Dina Raketa)

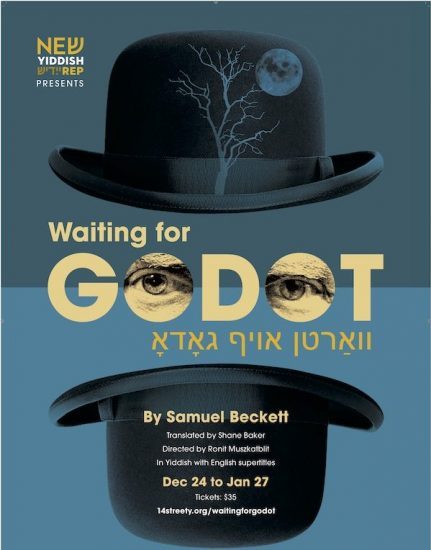

VARTN AF GODOT

Theater at the 14th Street Y

344 East 14th St. at First Ave.

Saturday – Tuesday through January 27, $35

646-395-4310

www.newyiddishrep.org

14streety.com

In October 2013, New Yiddish Rep teamed up with the Castillo Theatre to present the first-ever Yiddish version of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot (Vartn af Godot) in honor of the play’s sixtieth anniversary. New Yiddish Rep has now brought it back for an encore run at the Theater at the 14th Street Y, shedding new light on the oft-produced masterwork about the futility of human existence. I’ve recently seen it in English with septuagenarians Sir Patrick Stewart as Vladimir (Didi) and Sir Ian McKellen as Estragon (Gogo) on Broadway and with thirtysomething Irish actors Marty Rea as Didi and Aaron Monaghan as Gogo in the Druid’s adaptation at Lincoln Center’s White Light Festival. I heard Bill Irwin discuss the play at length in his one-man presentation On Beckett last year at the Irish Rep. But none of that prepared me for the NYR version, in which Beckett’s existential antiheroes Vladimir and Estragon are portrayed as a pair of alter kockers, heavily bearded old Jewish men complaining about life. Eli Rosen, a late replacement for Rafael Goldwaser, is the tall, thinner Vladimir, while company cofounder and artistic director David Mandelbaum reprises his 2013 role as the short and stout Estragon in this translation by Shane Baker (who played Didi in 2013), directed by Ronit Muszkablit.

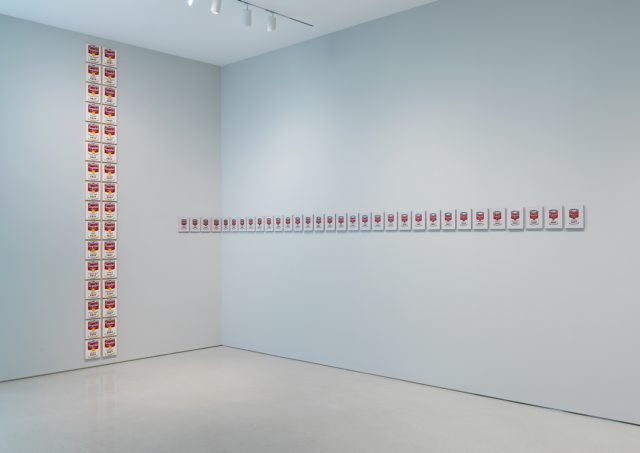

Pozzo (Gera Sandler) tries to explain himself as Estragon (David Mandelbaum), Lucky (Richard Saudek), and Didi (Eli Rosen) look on (photo by Dina Raketa)

“Nothing to be done,” Estragon says at the beginning, and such desultory phrases, so familiar to Beckett enthusiasts, have an astonishing resonance in Yiddish, as if the old man with the thick accent is carrying the burden of his people’s legacy. (English surtitles are crookedly projected on crooked wood at the back of the stage.) Later, Vladimir asks, “Was I sleeping, while the others suffered?” The two men are waiting for someone named Godot to arrive, but they don’t know why. While wandering around the small, rectangular space — which features a collection of junk that has been organized into a place to sit, along with a dilapidated backyard umbrella serving as a tree, bare save for a few dead leaves and some string (the set designer is George Xenos) — they talk about carrots, body odor, suicide, and memory. They also bring up Jesus, the Bible, repentance, the Dead Sea, crucifixion, and other religious topics that take on sometimes startling connotations when coming from Jews. For example, several references, including to a charnel-house, a camp, the loss of basic human rights, and skeletons and corpses, recalled the Holocaust, something that did not leap out at me when watching other productions or reading the play. And Pozzo’s (Gera Sandler) treatment of Lucky (Richard Saudek) evokes both anti-Semitism and the enslavement of the Jews. Beckett was not about to address such direct interpretations, but he did write Godot in the aftermath of WWII, during which he was part of the French Resistance and at one point escaped the Gestapo. So it’s not far-fetched to believe the Holocaust was on his mind to some degree while writing the play (in French), although in no way am I asserting that’s what it is specifically about.

The NYR adaptation moves too slowly, and the slapstick — Beckett includes moments of vaudeville-like physical comedy, inspired by his love of Laurel and Hardy — is tentative and ineffective, which is unfortunate, since so much of the rest of the production is solid and engaging. Rosen and Mandelbaum, who both appeared in NYR’s God of Vengeance and Awake and Sing! (among others), make a lovely pair — it’s easy to believe that the characters have been waiting for the mysterious Godot for a long, long time, arguing over who is suffering more. Saudek (Eager to Lose, Balls) excels as Lucky, delivering the protracted stream-of-consciousness monologue in a breathless fury that sounds sensational in Yiddish. And through it all is an unmistakable Jewishness, as if Godot is coming to guide Gogo and Didi to freedom in Israel, which had become a state only a few months before Beckett began work on the play. “I remember the maps of the Holy Land. Coloured they were. Very pretty,” Estragon tells Vladimir, continuing, “The Dead Sea was pale blue. The very look of it made me thirsty. That’s where we’ll go, I used to say, that’s where we’ll go for our honeymoon. We’ll swim. We’ll be happy.” Vartn af Godot will continue to bring happiness to theatergoers of all religious — or nonreligious — persuasions at the 14th Street Y through January 27 as part of the institution’s Season of War + Peace. (Fans of Yiddish theater should also check out the return of Tevye Served Raw at the Playroom Theater and the much-deserved extension of the National Yiddish Theatre Folksbiene’s Fiddler on the Roof in Yiddish at Stage 42.)