Martha Rosler’s A Gourmet Experience and Objects with No Titles are part of Jewish Museum retrospective (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

The Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Ave. at 92nd St.

Through March 3, $8-$18, pay-what-you-wish Thursday from 5:00 – 8:00, free Saturday

212-423-3200

thejewishmuseum.org

www.martharosler.net

In November 2012, I tried to buy a mahjongg case from renowned artist Martha Rosler as part of her MoMA atrium presentation “Meta-Monumental Garage Sale,” but alas, we couldn’t agree on a price. However, I’ve completely bought into the Brooklyn-born artist and activist’s latest show, “Irrespective,” an involving survey exhibition continuing at the Jewish Museum through March 3. “We need to be out there, but we also need to be in here, because otherwise the art world will go on doing the things it’s done in the way it’s done it, and that is not really the best that art can be,” Rosler explains on the audioguide. “It’s hard for me to look at my own life as other than just keeping on with doing what I was doing, which was a tripartite thing: making work, writing about ways of thinking about the world and about the production of art, and teaching.” That perspective shines through in the exhibit, which includes photography, sculpture, video, text, and installation going back five decades, taking on war, advertising, mass media, political leaders, the education system, modes of travel, and more from a decidedly feminist angle.

Martha Rosler, Prototype (Freedom Is Not Free), resin, composite, metal, paint, and printed transfers, 2006 (photo by twi-ny/mdr)

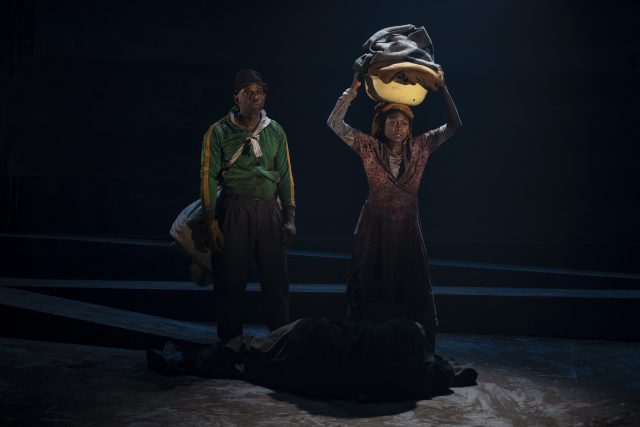

Curators Darsie Alexander and Shira Backer and designers New Affiliates, in close collaboration with Rosler, have reconfigured the museum space, which is laid out almost like a maze as visitors go from gallery to gallery in whichever order they choose, following no specific pattern as they encounter Rosler’s oeuvre uniquely, on their own path, echoing the range of her subject matter and media. (However, it is loosely chronological if you go counterclockwise.) As you enter, to your left is Prototype (Freedom Is Not Free), a giant mechanical leg that threatens to kick you; it relates to the prosthetics soldiers need after losing a limb to an IED, while the inclusion of images of stiletto heels invokes women warriors as well as wives, mothers, girlfriends, and sisters who care for men when they come home from battle seriously wounded. Rosler has revisited her “House Beautiful” series, in which she takes magazine and newspaper ads promoting domesticity, featuring suburban women doing what was considered women’s work, and places war images over specific parts. A Gourmet Experience consists of a long table set for a banquet and audio and video dealing with cooking, serving, and eating; nearby is a new iteration of Rosler’s 1970s installation Objects with No Titles, a collection of soft sculptures made with women’s undergarments, coming in all shapes and sizes.

In her most influential and well known video, Semiotics of the Kitchen, Rosler creates a new kind of verbal and physical language using standard utensils and her body. Food, labor, and power structures are highlighted in such photographic series as “Air Fare,” “North American Waitress, Coffee-Shop Variety (Know Your Servant Series, No. 1),” and “A Budding gourmet: food novel 1.” On the audioguide she notes, “Who doesn’t like food, especially if you’re Jewish? Our entire domestic life is centered on the question of reproduction and maintenance; maintenance involves, aside from cleaning the house and doing the laundry, making sure everyone is fed three times a day. And you’re supposed to be good at it.” In the video Born to Be Sold: Martha Rosler Reads the Strange Case of Baby $/M, Rosler defends Mary Beth Whitehead, a surrogate mother who decided to keep the baby she was carrying for adoptive parents, while in Unknown Secrets (The Secret of the Rosenbergs) she employs a handout, photographs, a stenciled towel, and a package of Jell-O to detail how Ethel Rosenberg might have been framed.

Martha Rosler wields a sharp knife in Semiotics of the Kitchen (black-and-white video with sound, Jewish Museum, New York)

Reading Hannah Arendt (Politically, for an Artist in the 21st Century) comprises mylar panels hanging from the ceiling, printed with quotes from the German Jewish theorist’s 1951 book, The Origins of Totalitarianism, including this paraphrasing of Noam Chomsky: “‘Detachment and equanimity’ in view of ‘unbearable tragedy’ can indeed be ‘terrifying.’” Photos of airports are accompanied by such phrases as “haunted trajectories,” “interpenetration of terrors,” and “vagina or birth canal?” In The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems, Rosler snaps photos along the Bowery but without any people in them; instead, she adds various words associated with drunkenness, but the absence of the denizens of Skid Row is palpable. In “Greenpoint Project,” she documents the gentrification of the neighborhood where she’s lived for nearly forty years. And in “Rights of Passage,” she traces her commute using a toy panoramic camera.

While some of the work is repetitive thematically, Rosler argues on the audioguide that “when people say, ‘Wait, you did that already,” I would say: ‘That’s right, I did that already, and so did we. And how is what we’re doing now different from what we did then?’” The Jewish Museum show might go back fifty years, but it doesn’t feel old in the least, as so much of what Rosler stands for and has been exploring throughout her career is still on the line, from war to gender inequality, from corrupt politicians to reproductive rights. That she does so with a wickedly wry sense of humor — she has referred to herself as a “standup comic” — only makes it all the more accessible, using laughter as a decoy. “The Monumental Garage Sale is a decoy,” she tells Molly Nesbit in a catalog interview. “Cooking and its customs and material objects are decoys: they provide an entry into daily life — roles and procedures that have become naturalized or normalized.” Thus, I might not have purchased that mahjongg case at MoMA, but that was just a decoy as well.

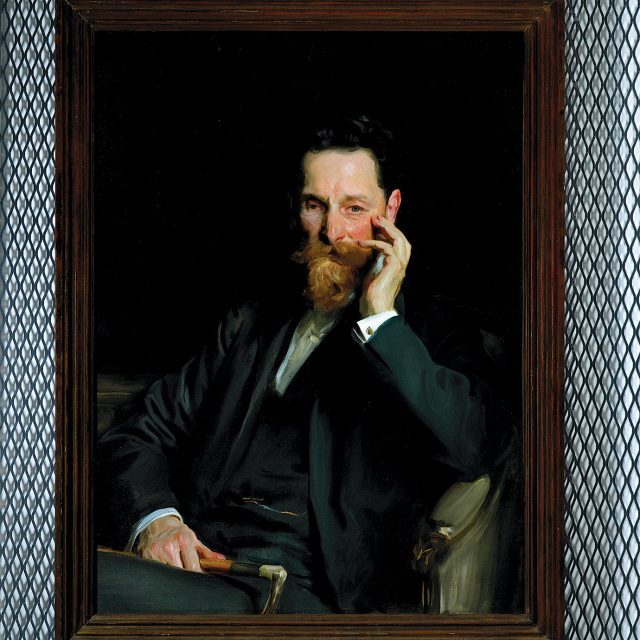

“It is not enough to refrain from publishing fake news . . . accuracy is to a newspaper what virtue is to a woman,” Joseph Pulitzer, voiced by a thickly Hungarian-accented Liev Schreiber, says in Oren Rudavsky’s Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People, opening March 1 at the Quad. Made for PBS’s American Masters series, the documentary, narrated by Adam Driver, gets off to a slow start, with numerous talking heads, wearisome reenactments, and modern-day B-roll shots. There’s some fascinating information about Pulitzer, who was born in Hungary in 1847, came to America penniless to fight in the Civil War, and eventually built a publishing empire that made him extremely wealthy even as he still fought aggressively for the poor, the disenfranchised, the overlooked, the underrepresented. Of course, Rudavsky (A Life Apart: Hasidism in America) — who directed the film, wrote it with Robert Seidman and editor Ramon Rivera Moret, and produced it with Seidman and Andrea Miller — had limited pictorial resources for the first half of Pulitzer’s life, before photography became more mainstream and before Pulitzer bought and ran the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York World.

“It is not enough to refrain from publishing fake news . . . accuracy is to a newspaper what virtue is to a woman,” Joseph Pulitzer, voiced by a thickly Hungarian-accented Liev Schreiber, says in Oren Rudavsky’s Joseph Pulitzer: Voice of the People, opening March 1 at the Quad. Made for PBS’s American Masters series, the documentary, narrated by Adam Driver, gets off to a slow start, with numerous talking heads, wearisome reenactments, and modern-day B-roll shots. There’s some fascinating information about Pulitzer, who was born in Hungary in 1847, came to America penniless to fight in the Civil War, and eventually built a publishing empire that made him extremely wealthy even as he still fought aggressively for the poor, the disenfranchised, the overlooked, the underrepresented. Of course, Rudavsky (A Life Apart: Hasidism in America) — who directed the film, wrote it with Robert Seidman and editor Ramon Rivera Moret, and produced it with Seidman and Andrea Miller — had limited pictorial resources for the first half of Pulitzer’s life, before photography became more mainstream and before Pulitzer bought and ran the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and the New York World.

Writer-director Benedikt Erlingsson has followed up his dazzling 2015 debut,

Writer-director Benedikt Erlingsson has followed up his dazzling 2015 debut,