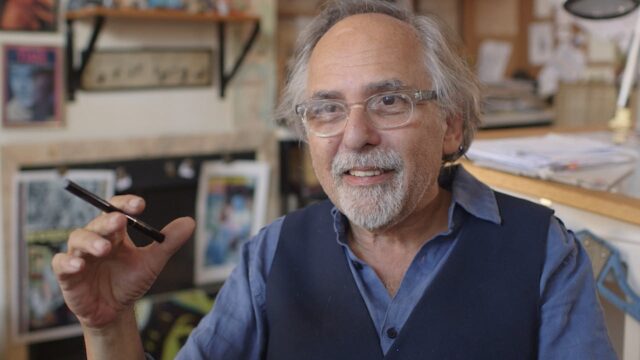

Martha Graham Dance Company will perform Baye & Asa’s Cortege and more in Joyce season (photo by Steven Pisano)

MARTHA GRAHAM DANCE COMPANY: DANCES OF THE MIND

Joyce Theater

175 Eighth Ave. at 19th St.

April 1-13, $62-$82

212-645-2904

www.joyce.org

marthagraham.org

What’s old is new again.

The Martha Graham Dance Company brings its ninety-ninth season to the Joyce for two weeks of classics, world premieres, and reimaginings of familiar pieces, in one case using — gasp! — AI.

From April 1 to 13, MGDC will present “Dances of the Mind,” three programs as part of its continuing GRAHAM100 celebration, preparing for its official centennial next year. Program A consists of Graham’s 1958 Clytemnestra Act II, with an original score by Halim El-Dabh and set by Isamu Noguchi; Baye & Asa’s Cortege, a world premiere about Charon the ferryman, inspired by Graham’s 1967 Cortege of Eagles, with music by Jack Grabow and costumes by Caleb Krieg; Xin Ying’s Letter to Nobody, based on Graham’s 1940 Letter to the World, this time honoring Graham and her legacy, incorporating generative media and AI technology, along with an Emily Dickinson poem (“I’m Nobody! Who are you? / Are you – Nobody – too? / Then there’s a pair of us!”), to craft a duet with Graham, Erick Hawkins, and Merce Cunningham; and Hofesh Shechter’s kinetic 2022 CAVE, with music by Âme and Shechter and costumes by Krieg.

Program B comprises Graham’s 1935 solo Frontier: American Perspective of the Plains, honoring the spirit of the pioneer woman, with a score by Louis Horst and set by Isamu Noguchi; two lost 1920s solos, Revolt and Immigrant, reimagined by Graham 2 director Virginie Mécène through extensive research; a new production of Agnes de Mille’s Rodeo, with Gabe Witcher’s bluegrass arrangement of Aaron Copland’s famous score, costumes by Oana Botez, and set by two-time Tony winner Beowulf Boritt; and Jamar Roberts’s 2024 We the People, which Roberts explains “is equal parts protest and lament, speculating on the ways in which America does not always live up to its promise,” with music by Rhiannon Giddens (arranged by Witcher) and costumes by Karen Young.

The third program brings together Graham’s 1943 Deaths and Entrances, made while Graham was contemplating faith and despair and inspired by the lives of Anne, Emily, and Charlotte Brontë, with music by Hunter Johnson, set by Arch Lauterer, and costumes by Oscar de la Renta; Graham’s 1947 Errand into the Maze, a duet based on the myth of Theseus and the Minotaur, with a score by Gian Carlo Menotti and set by Noguchi; and CAVE.

In addition, the April 1 gala features Clytemnestra Act II and Cortege, the April 5 University Partners Showcase highlights university and high school dancers performing works by Graham, Hawkins, José Limón, and others, the April 12 family matinee presents Graham’s 1935 call-to-action Panorama, Rodeo, and We the People, and there will be a Curtain Chat following the April 9 show.

Founded in 1926 in a tiny Carnegie Hall studio in midtown Manhattan, MGDC has an illustrious history involving a wide range of remarkable collaborators; the current troupe includes So Young An, Ane Arieta, Laurel Dalley Smith, Zachary Jeppsen-Toy, Meagan King, Lloyd Knight, Rayan Lecurieux-Durival, Antonio Leone, Devin Loh, Amanda Moreira, Ethan Palma, Jai Perez, Anne Souder, Matthew Spangler, Richard Villaverde, Leslie Andrea Williams, and Xin Ying.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]