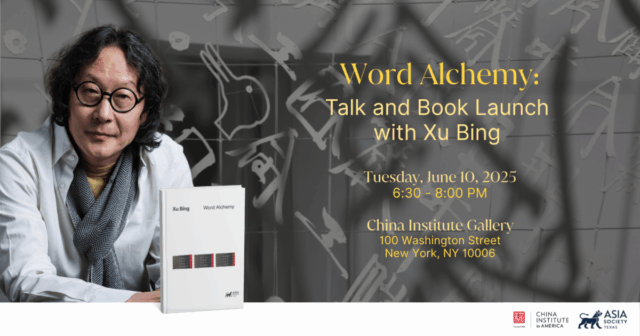

Em (Lisa Emery) and George (Reed Birney) take stock of their life together in Donald Margulies’s Lunar Eclipse (photo by Joan Marcus)

LUNAR ECLIPSE

The Pershing Square Signature Center

The Irene Diamond Stage

Tuesday – Sunday through June 22, $74-$114

2st.com

Donald Margulies’s immeasurably moving and intelligent Lunar Eclipse begins with a man (Reed Birney) sitting in a folding chair under a tree in the middle of a grassy field, crying inconsolably. He tries to hide his sorrow when a woman (Lisa Emery) arrives, but soon they are both digging deep into their lives as the earth passes between the sun and the moon.

The couple is named George and Em, after George Gibbs and Emily Webb, the neighbors who fall in love in Thornton Wilder’s Our Town. Although the play is not specifically about those two characters, it does echo Wilder’s approach, making them represent any wife and husband looking back after fifty years, the good times and the bad. It’s nearly impossible to not imagine yourself in one of those chairs — regardless of your current age — next to your longtime partner, taking stock of your accomplishments and failures as the sky turns from bright to dark to bright again.

For ninety minutes, George and Em bicker over minute things, discuss their children, remember their first night together, and honor the many dogs they had, buried around them in that field. Although no time period is given, cellphones never appear. George and Em talk about their health problems; George is afraid he’s starting to lose his mind. He says, “Feel like I’m at sea, sometimes, in the middle of a storm. Looking for a place to land only there’s no land in sight.” Em replies, “You’re the sharpest man I know.” But George insists he is changing, and not for the better. “Isn’t that something? To think that we’re here? At this stage? Already? Look at us: Almost done. Lights out.”

As the total eclipse begins, George pulls out his binoculars, laments having had his telescope stolen, and hopes to see the rare Japanese Lantern Effect. Em asks George why he was crying, and although he is initially hesitant, he eventually tells her. They talk a lot about love and death.

Describing a troubling experience he’d had very early that morning, a kind of walking nightmare, George says, “My heart . . . was racing . . . I could feel blood rushing to my head. I could hear it in my ears. Afraid if I said anything, if I made any sound at all, if I’d budged one inch, everything would just . . . crack.”

She kisses his hand, and he wonders why she did that. He is worried about the future of humanity. She asks if she has ever done anything that surprised him. He’s sorry to hear about her sadness. In some ways they evoke not only Wilder’s George and Emily but also Edward Albee’s George and Martha from Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, although not nearly as extreme, nonviolent, and relatively sober.

They’re not rich, they don’t have a close, loving family, and they recently said goodbye to their last dog, but they still care about each other, even if he doesn’t want to admit it.

George: Anything I can do to help . . .

Em: You mean that?

George: Of course I mean that.

Em: Thank you. That’s kind of you to say.

George: I’m not being kind. I’m your husband.

Em (Lisa Emery) and George (Reed Birney) remember the good times and the bad in beautiful Second Stage play (photo by Joan Marcus)

Em sums up their life — all of our lives — when she then says, “The worst thing in the world that could possibly happen happens and you go to sleep and morning comes and whataya know, you wake up and you’re still breathing. You didn’t die during the night. That’s your punishment, I guess: You live another day. And all the days after that.”

Presented by Second Stage at the Signature Center, Lunar Eclipse is a near-masterpiece by the Brooklyn-born, New Haven–based Margulies, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2000 for Dinner with Friends, was a finalist for two other Pulitzers (for Sight Unseen and Collected Stories), and won the Thornton Wilder Prize for literary translation in 2018. Margulies dedicated the work to his father-in-law, George Street, a Kentucky farmer who died in 2010.

Walt Spangler’s set is a lovely, inviting grassy expanse beautifully lit by Amith Chandrashaker, with Sinan Refik Zafar’s nature sounds encompassing the theater, immersing the audience in the experience, along with Grace Mclean’s gentle music. S. Katy Tucker’s video projections follow the course of the eclipse in the sky behind the actors, who are dressed in Jennifer Moeller’s casual costumes. My lone quibble is when dark clouds are projected as George mentions dark clouds hanging over him.

Drama League nominee Kate Whoriskey (Clyde’s, Sweat) directs the show with a compassionate, tender hand, giving plenty of room for Margulies’s poetic dialogue to shine out of the shadows. For the next lunar eclipse, you’ll want to find a grassy, private space where you can sit next to your loved one and enjoy the event, but be careful what you share.

Tony winner Birney (Chester Bailey, The Humans) and Drama Desk nominee Emery (Six Degrees of Separation, A Kind of Alaska) are sensational together, he both gentle and brash as George, who admits to being disappointed with how his life ended up, she touching and considerate as Em, who believes she did the best she possibly could.

Which is all any of us can ask for.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]