A Thousand Ways (Part Three): Assembly brings strangers together at the New York Public Library (photo courtesy 600 Highwaymen)

UNDER THE RADAR FESTIVAL

Public Theater and other venues

January 4-22, free – $60

publictheater.org

The Public Theater’s Under the Radar Festival is back and in person for its eighteenth iteration, running January 4-22 at the Public as well as Chelsea Factory, NYU Skirball, La MaMa, BAM, and the New York Public Library’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation branch. As always, the works come from around the world, a mélange of disciplines that offers unique theatrical experiences. Among this year’s selections are Jasmine Lee-Jones’s seven methods of killing kylie jenner, Annie Saunders and Becca Wolff’s Our Country, Roger Guenveur Smith’s Otto Frank, Rachel Mars’s Your Sexts Are Shit: Older Better Letters, Kaneza Schaal’s KLII, and Timothy White Eagle and the Violet Triangle’s The Indigo Room.

In addition, “Incoming! — Works-in-Process” features early looks at pieces by Mia Rovegno, Miranda Haymon, Nile Harris, Mariana Valencia, Eric Lockley, Savon Bartley, Raelle Myrick-Hodges, and Justin Elizabeth Sayre, while Joe’s Pub will host performances by Eszter Balint, Negin Farsad, Julian Fleisher and his Rather Big Band, Salty Brine, and Migguel Anggelo.

Below is a look at four of the highlights.

600 HIGHWAYMEN: A THOUSAND WAYS (PART THREE): AN ASSEMBLY

The New York Public Library, Stavros Niarchos Foundation Library

455 Fifth Ave. at Fortieth St., seventh floor

January 4-22, free with advance RSVP

publictheater.org

At the January 2021 Under the Radar Festival, the Obie-winning 600 Highwaymen presented A Thousand Ways (Part One): A Phone Call, a free hourlong telephone conversation between you and another person, randomly put together and facilitated by an electronic voice that asks both general and intimate questions, from where you are sitting to what smells you are missing, structured around a dangerous and lonely fictional situation that is a metaphor for sheltering in place. The company followed that up with the second part, An Encounter, in which you and a stranger — not the same one — meet in person, sitting across a table, separated from one another by a clear glass panel, with no touching and no sharing of objects. In both sections, I bonded quickly with the other person, making for intimate and poignant moments when we were all keeping our distance from each other.

Now comes the grand finale, Assembly, where sixteen strangers at a time will come together to finish the story at the New York Public Library’s Stavros Niarchos Foundation branch in Midtown. Written and created by Abigail Browde and Michael Silverstone, A Thousand Ways innovatively tracks how the pandemic lockdown influenced the ways we interact with others as well as how critical connection and entertainment are.

Palindromic show makes US premiere at Under the Radar Festival (photo courtesy Ontroerend Goed)

ONTROEREND GOED: Are we not drawn onward to new erA

BAM Fishman Space

321 Ashland Pl.

January 4-8, $45

publictheater.org

www.bam.org

What do the following three statements have in common? “Dammit, I’m mad.” “Madam in Eden, I’m Adam.” “A man, a plan, a canal – Panama.” They are all palindromes, reading the same way backward and forward. They also, in their own way, relate to Ontroerend Goed’s Are we not drawn onward to new erA, running January 4-8 at BAM’s Fishman Space. Directed by Alexander Devriendt, the Belgian theater collective’s seventy-minute show features a title and a narrative that work both backward and forward as they explore climate change and the destruction wrought by humanity, which has set the Garden of Eden on the path toward armageddon. But maybe, just maybe, there is still time to save the planet if we come up with just the right plan.

PLEXUS POLAIRE: MOBY DICK

NYU Skirball

566 LaGuardia Pl.

January 12-14, $40

publictheater.org

nyuskirball.org

The world is obsessed with Moby-Dick much the way Captain Ahab is obsessed with the great white itself. Now it’s Norwegian theater company Plexus Polaire and artistic director Yngvild Aspeli’s turn to harpoon the story of one of the most grand quests in all of literature. Aspeli (Signaux, Opéra Opaque, Dracula) incorporates seven actors, fifty puppets, video projections, a drowned orchestra, and a giant whale to transform Herman Melville’s 1851 novel into a haunting ninety-minute multimedia production at NYU Skirball for four performances only, so get on board as soon as you can.

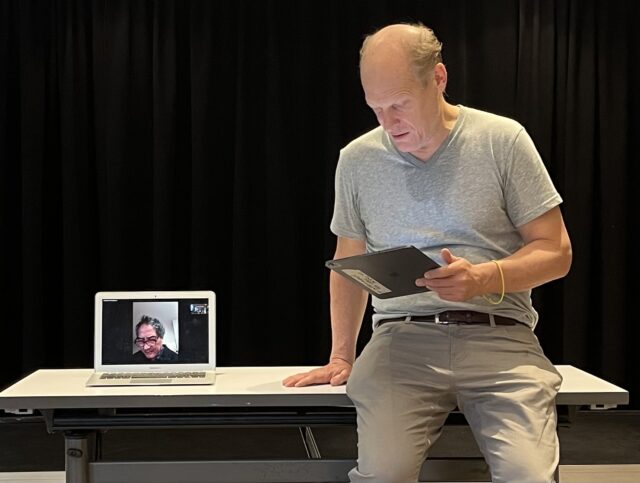

Brian Mendes and Jim Fletcher get ready for NYCP’s Field of Mars (photo courtesy New York City Players)

NEW YORK CITY PLAYERS: FIELD OF MARS

NYU Skirball

566 LaGuardia Pl.

January 19-22, 24-29, $60

publictheater.org

nyuskirball.org

I’ll follow Richard Maxwell and New York City Players anywhere, whether it’s on a boat past the Statue of Liberty (The Vessel), an existential journey inside relationships and theater itself (The Evening, Isolde) and outside time and space (Paradiso, Good Samaritans), or even to the Red Planet and beyond. Actually, his newest piece, Field of Mars, playing at NYU Skirball January 19-29, refers not to the fourth planet from the sun but to the ancient term for a large public space and military parade ground. Maxwell doesn’t like to share too much about upcoming shows, but we do know that this one features Lakpa Bhutia, Nicholas Elliott, Jim Fletcher, Eleanor Hutchins, Paige Martin, Brian Mendes, James Moore, Phil Moore, Steven Thompson, Tory Vazquez, and Gillian Walsh and that the limited audience will be seated on the stage.

Oh, and Maxwell noted in an email blast: “Field of Mars: A chain restaurant in Chapel Hill is used as a way to measure the progress of primates, from hunter/gatherer to fast casual dining experience. Topics covered: Music, Food, Nature, and Spirituality. . . . I also wanted to take this opportunity to tell parents regarding the content of Field of Mars: my kids (aged 11 and 15) will not be seeing this show.”