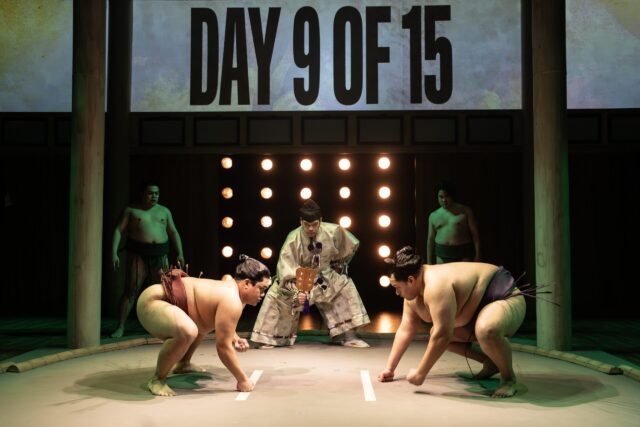

The Mint has resurrected Harold Brighouse’s 1914 political satire Garside’s Career (photo by Maria Baranova)

GARSIDE’S CAREER

The Mint Theater at Theatre Row

410 West 42nd St. between Ninth & Tenth Aves.

Tuesday – Sunday through March 15, $39-$79

minttheater.org

www.theatrerow.org

I’ve written before about how one of the many joys of experiencing a work by the Mint Theater is not just the exquisite sets but the set changes; those in the know do not leave their seats during intermission but instead watch the transformation of the stage from one act to another, executed with expert precision, a choreographed dance that deservedly receives its own round of applause.

In the company’s latest show, a lovely revival of Harold Brighouse’s savvy 1914 political satire Garside’s Career, director Matt Dickson incorporates the set changes into the flow of the play; all the elements of Christoper Swader and Justin Swader’s scenic design are onstage through the entire 130 minutes (including intermission), piled in the back and the corners. As the story moves from Mrs. Garside’s working-class Midlanton cottage in Lancashire to Sir Jasper Mottram’s elegant house to Peter Garside’s extravagant Temple district home in London and back to the cottage, the furniture is switched out, mimicking Peter’s intense ambition, his past and future hovering around his present.

An engineer with a love of public speaking, Peter (Daniel Marconi) has been studying at night to earn a bachelor’s degree, with the support of his girlfriend, Margaret Shawcross (Madeline Seidman), a shy teacher who Mrs. Garside (Amelia White) believes is not good enough for her only child. Waiting for Peter to return home with his test results, Margaret tells Mrs. Garside, “I’m fearful of the odds against him — the chances the others have and he hasn’t. Peter’s to work for his living. They’re free to study all day long. Oh, if he does it, what a triumph for our class. Peter Garside, the Board School boy, the working engineer, keeping himself and you, and studying at night for his degree.”

Peter indeed has good news, explaining that he and Margaret can now marry, and he can be a journalist and go on lecture tours. “Peter, you didn’t do it for that!” Margaret declares, explaining that if they get married, she will have to give up her job as a teacher and that she is not in favor of his lecturing. Peter responds, “I did it for you. But I mean to enjoy the fruits of all this work. Public speaking’s always been a joy to me. You don’t know the glorious sensation of holding a crowd in the hollow of your hand, mastering it, doing what you like with it.”

Margaret makes herself clear, warning him of the intoxication of power, “I’ve seen men ruined by this itch to speak. You know them. Men we thought would be real leaders of the people. And they spoke, and spoke, and soon said all they had to say, became mere windbags trading on a reputation. Don’t be one of these, Peter. You’ve solider grit than they. The itch to speak is like the itch to drink, except that it’s cheaper to talk yourself tipsy.”

Peter’s boss, Ned Applegarth (Paul Niebanck), then arrives, with Peter’s colleagues Denis O’Callaghan (Erik Gratton) and Karl Marx Jones (Michael Schantz), not only to celebrate Peter’s success, but to convince him to run for a newly open Parliament seat, as a member of the Socialist Labour Party.

Denis spells it out: “We want you for another nail in the coffin of capitalism, another link in the golden chain that’s dragging us up from slavery the way we’ll be free men the day that chain’s complete.”

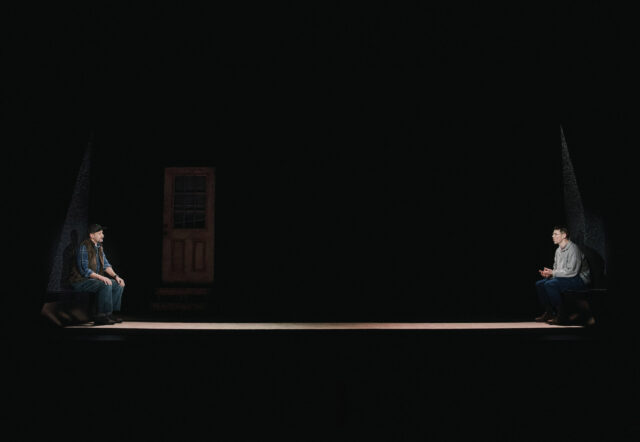

Effete siblings Freddie (Avery Whitted) and Gladys Mottram (Sara Haider) welcome Peter Garside (Daniel Marconi) into their elegant home in Mint production (photo by Maria Baranova)

Peter sees this as a great opportunity for fortune, fame, and more, but Margaret is hesitant, especially when Peter says that they can use their upcoming nuptials as an “advertisement” in the campaign. Ultimately, she decides that if Peter goes ahead with his candidacy, she will support the cause but will break their engagement, which delights Mrs. Garside.

Soon Peter is hobnobbing with the local wealthy Mottram clan: the haughty Lady Mottram (Melissa Maxwell), her flirtatious daughter, Gladys (Sara Haider), and her cheeky son, Freddie (Avery Whitted). They are initially enlisted by the opposition party to distract Peter from his campaign, but an attraction develops between him and Gladys, complicating matters, especially after he wins the election and heads off to London, his ambition growing by the minute, spiraling out of control.

The title character was inspired in part by Victor Grayson, a Liverpool carpenter’s son who became a fiery orator and controversial member of Parliament of whom Winston Churchill said in 1908, “The Socialism of the Christian era was based on the idea that, ‘All mine is yours,’ but the Socialism of Mr Grayson is based on the idea that ‘All yours is mine.’” Marconi (Sweeney Todd, The Mountains Look Different) portrays Peter with a gleam in his eye and a jaunt in his step; Haider (Partnership, Wait Until Dark) is enthralling as the sexy Gladys, while Seidman (Becomes a Woman, Partnership) excels as the steadfastly moral and independent Margaret, Gladys’s rival.

Garside’s Career is a solid, well-structured if somewhat slight comedy of manners with plot lines that relate to contemporary political situations, so it’s surprising that Dickson’s exemplary production is the New York premiere and, possibly, the first major US presentation since a Boston run in 1919. Brighouse also wrote the popular Hobson’s Choice, the oft-revived 1915 play that was adapted into an Oscar-winning 1954 film, the 1966 Broadway musical Walking Happy, and a 1989 ballet.

Thankfully, the Mint, as is its mission, has resurrected yet another long-forgotten gem with style and grace — and another memorable set.

[Mark Rifkin is a Brooklyn-born, Manhattan-based writer and editor; you can follow him on Substack here.]